Hormesis: Using Stress to Enhance Health and Longevity

What doesn't kill you makes you stronger.

It is idleness that is the curse of man — not labour. Idleness eats the heart out of men as of nations, and consumes them as rust does iron. — Samuel Smiles

From the perspective of biology, our bodies need stress. A life without hardship is not only not worth living, but actively harmful to our health.

Too much sitting quietly wreaks havoc on our body, which was designed for movement. Indeed, many diseases of modernity (cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, etc.) have been tied to physical inactivity. In fact, physical inactivity has been implicated as a direct cause of these chronic conditions.

In 2004 , the term “sedentary death syndrome” (SeDS) was coined to highlight the role of inactivity in preventable deaths worldwide.

As idleness leads to ill-health, so does excess: whether it be excessive energy intake, alcohol consumption, or exposure to environmental toxins.

But good things too, can also be overdone. A moderate to high amount of exercise is great for health. But, taken to extremes, exercise can have potentially harmful effects. You can even drink too much water, a condition known as water intoxication that causes blood sodium levels to drop too low (hyponatremia), causing brain swelling and death.

Biology, it seems, is about finding the sweet spot.

This biological sweet spot has a name — hormesis.

All things are poison, and nothing is without poison, only the dose permits something not to be poisonous. — Paracelsus circa 16th century

Hormesis is “a process in which exposure to a low dose of a chemical agent or environmental factor (stress) that is damaging at higher doses, induces an adaptive beneficial effect on the cell/organism.”

Hormesis is a biphasic physiological response, where a stress is beneficial at low doses, but becomes harmful or toxic at higher doses.

Put another way. The right amount of stress leads to growth.

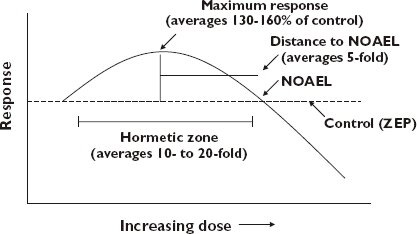

Hormesis functions as a bell-shaped curve. Provide too little of a stress or stimulus (the far left) and you get very little or no response — the organism isn’t stressed and doesn’t adapt.

Provide too much (far right) and you stress the organism too much — the body can’t handle the load placed upon it and breaks down.

In the middle is the “hormetic zone” where beneficial adaptations occur.

As the dose-response graph above shows, there is a maximum response, occurring at the optimal dose of stress, which, theoretically, yields the most benefit to the organism.

Some stress is good. Too much stress…not so much.

It’s claimed that hormesis is an “ability” we adapted in order to avoid extinction. Indeed, to survive harsh conditions and toxic environments, organisms needed to evolve an ability to deal with a stress and then come back stronger so when the same stress occurred again, they could cope. In a way, biology “learned” to adapt.

Certain stress response molecules such as heat shock proteins, antioxidants, and growth factors are released in response to stimuli such as heat, oxidative stress/reactive oxygen species, toxins, and mechanical damage. All of these factors lead to adaptive responses that makes us stronger and more resilient in the long run.

A final benefit to hormesis may be related to reproduction. Some studies have found that inducing hormesis using radiation (to flies) improves their sexual performance, and females found males more attractive about 12 days after they experienced this hormetic stress. Use that information as you’d like.

Putting biology aside for a moment. Hormesis can also be relevant from a self-fulfillment perspective — at least I’d like to think so.

Socrates said that “the unexamined life is not worth living”—nor is the unchallenged life. Overcoming obstacles — whether physical, mental, or emotional — is intrinsically satisfying and, I would argue, necessary to truly feel like one is living with some sort of meaning and purpose.

Furthermore, we must continuously encounter even larger and more interesting challenges as we go through our lives. Indeed, the concept of the hedonic treadmill reminds us that, eventually, after a stressful or even a blissful event, we will return to baseline and need more of the same stimulus to achieve the desired response.

For this reason, it seems necessary in our modern society to artificially induce hormesis. We no longer deal with much environmental stress, so we must make our own. A variety of hormetic stimuli can increase longevity, healthspan, and performance.

These are exercise, calorie restriction/fasting, and heat and cold exposure.