Is VO2 Max the Best Measure of Fitness and Performance?

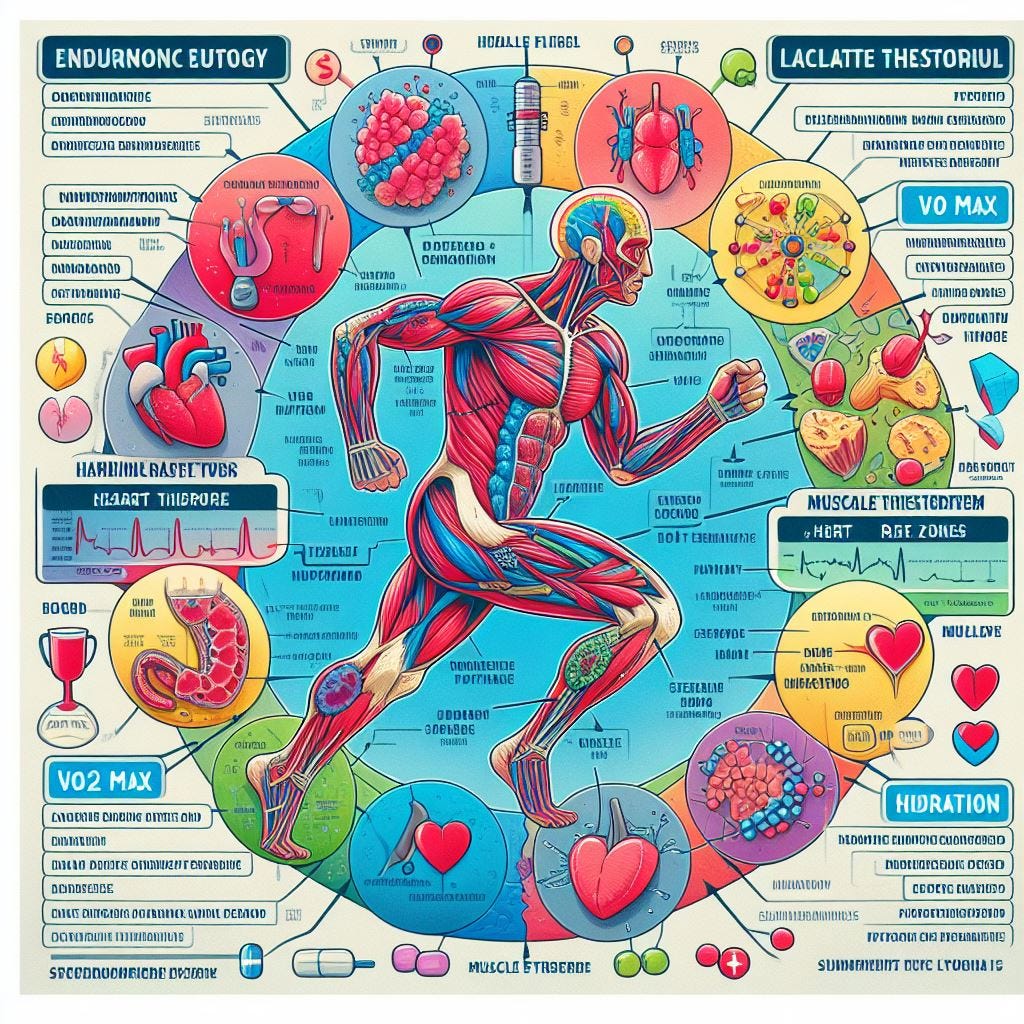

Maximal oxygen consumption may be an important but incomplete part of the big picture of endurance. Can we do better?

Within exercise and sports science, no one measure has gotten more attention than VO2 max.

VO2 max refers to your maximum rate of oxygen consumption, and it’s typically measured during a maximal exercise test to exhaustion (they’re not fun, trust me). It is used as an indicator of an individual's cardiorespiratory fitness and is often used to demonstrate the effects of training.

VO2 max is also one of the main ways that researchers classify participants’ training status — with low and high VO2 max values indicating undertrained and highly trained participants, respectively. It’s very common for researchers to report training status to allow the generalizability of study results to inform training practices in the real world.

Due to the recent appreciation for VO2 max as an indicator of mortality risk, it’s also a “biomarker” that everyone’s concerned with measuring and improving. There is certainly evidence that a higher VO2 max can increase your odds of living a longer healthier life.

Maybe you’re using the VO2 max estimated from your fitness tracker to gauge whether a training program is working or not. This is a great way to identify trends in your fitness and can be useful if you’re interested in improving VO2 max for health- or performance-related reasons.

But are there other measures you should be more concerned with? Are we overemphasizing VO2 max?

Despite its widespread use in performance-based studies, there’s an ongoing debate among researchers as to whether VO2 max is the “best we can do” when it comes to classifying the training status of participants, measuring the effectiveness of a training intervention, and applying results of training studies to real-life exercise prescription.

Outside of a research context, this also applies to you. Are there other ways you can measure how fit you’re getting? Perhaps measures that are better predictors of performance?

A recent of ‘Viewpoint’ published in the Journal of Applied Physiology highlights limitations with the current use of VO2 max and suggests suitable alternatives.

The problem with VO2 max

If you take a random sample of adults and measure their VO2 max, there’s a good chance that the people with higher values will outperform those with lower values during an endurance race — a 10-kilometer run, for example.

But take a group of elite-level athletes, and VO2 max becomes less accurate in its prediction. It’s not always the guy or girl with the highest lab-measured VO2 max who wins the race — otherwise, why race at all?

This is because, while a high VO2 max may be a necessary prerequisite for elite-level endurance performance, it’s hardly sufficient.

There are a few other issues with using VO2 max as the sole marker of training status.

For one, there’s often a mismatch between participants’ VO2 max and their actual level of performance. Some studies refer to participants as “elite” in terms of their VO2 max values, even though they come nowhere close to elite-level ranks for performance-based measures.

Second, as stated earlier, VO2 max does not predict individual differences in performance among similar groups of athletes (e.g., elite cyclists or endurance runners).

Third, some athletes at the highest levels of competition have “inferior” VO2 max values (at least lower than you’d expect). They perform well despite having sub-elite oxygen consumption capacities.

Fourth, athletes with similar performance capabilities can have drastically different VO2 max levels.

Finally, performance/fitness can improve independent of changes in VO2 max!

We know that performance is influenced by much more than VO2 max. Indeed, the other “pillars of endurance performance” include exercise economy/efficiency and lactate threshold. There’s also a large difference in the relative percentage of VO2 max that each of us can sustain for a prolonged time.

Adding these physiological variables to VO2 max greatly improves our ability to predict performance.

All of this is to say that VO2 max cannot be used as the lone predictor of endurance performance, nor can it (or should it) be used as the only outcome to assess the effectiveness of an exercise training regimen. It doesn’t give enough information.

Proposing an alternative

If we want to improve our ability to classify people’s training status/fitness and more comprehensively measure our fitness gains, we need a comprehensive measure that is comprised of the physiological parameters including — but not limited to — VO2 max, exercise economy, and lactate threshold.

In the ‘Viewpoint’, one group of researchers argues that critical speed/critical power (CS/CP) is this measure.

Critical speed represents the hyperbolic relationship between speed and duration — as speed increases, the time that we’re able to sustain running at that speed decreases.

Critical speed is the asymptote of that relationship — it’s a speed we can theoretically maintain “forever” without task failure occurring. When we exceed our critical speed, it’s only a matter of time before we become too fatigued to continue and stop running. This also has a name — D prime (D’). In simple terms, D’ is the distance that you’re able to run after you’ve exceeded your critical speed.

The further you stray from critical speed (i.e., the faster you run), the less time you're able to sustain exercise. Faster running “uses up” more of our limited resource known as D’. Think of D’ as your “energy battery” above your critical speed.

Importantly, CS/CP offers the most comprehensive explanation of performance at various distances/durations and represents a threshold between steady exercise (that we can maintain) and nonsteady exercise (that we can’t maintain).

In other words, CS/CP is likely to be more relevant when performance is what we’re interested in and therefore, should be the measure that researchers use to characterize training status and they “should be encouraged to describe study participants based on the physiological parameters capable of best predicting performance across a wide range of intensities and to move away from reporting solely VO2 max.”

Not everyone agrees…

The counterpoint

In a series of replies to the editor, researchers from around the world hurried to comment, criticize, and propose alternatives to the viewpoints expressed above. Benchmarks of training status and training-induced improvements need to be more robust, so the argument goes, and neither VO2 max nor critical speed or power fit the bill.