Lifelong Endurance Exercise and Atherosclerosis: Concerning Trends and Emerging Evidence

Is working out too hard detrimental to heart health?

Exercise is the real fountain of youth.

There’s no better way to improve your chances of aging gracefully and reduce your risk of major noncommunicable diseases than to get adequate levels of physical activity. The benefits have been shown for both aerobic and resistance exercise, and even walking confers a significant advantage for healthspan and lifespan.

The risk reduction associated with exercise is substantial when moving from inactivity to some activity, and significant benefits can be achieved from getting the minimum weekly dose of exercise — 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise, or a combination of the two (polarized training involving a mix of easy “zone 2” training and high-intensity training is likely the most optimal way to address all aspects of metabolic and cardiovascular health).

Furthermore, a high VO2 max is one of the most potent predictors of all-cause mortality. Individuals with greater levels of aerobic fitness have lower all-cause mortality compared to less-fit individuals. The lowest risk is observed in people with so-called “elite” levels of aerobic fitness. In other words, there’s a high ceiling for the benefits of cardiorespiratory fitness when it comes to reducing your risk of death.

Despite these well-known benefits of exercise, in the recent decade, a series of interesting data have emerged that raise cautions about the potentially harmful effects of “too much” exercise.

There’s a hypothesis that athletes — namely competitive endurance athletes — by pushing their cardiovascular system to its limit for years upon years, may actually be doing more harm than good to their heart. High-intensity exercise, we must remember, is stressful. Blood pressure and heart rate spike, blood flow becomes turbulent, and the heart and arteries are subjected to high levels of mechanical stress and inflammation. Over time, these mechanisms may promote vascular remodeling, fibrosis, scarring, and atherosclerosis.

For these reasons, a debate continues to rage on as to whether a lifetime of strenuous exercise may actually be damaging to the cardiovascular system.

Lifelong exercise and atherosclerosis risk

In the MARC study, the lifelong exercise habits of 284 middle-aged men (average age of 55), all of whom were amateur athletes (i.e., recreational or locally competitive), were examined to determine the relationship between exercise volume, exercise intensity, and the risk for coronary artery calcification (CAC).

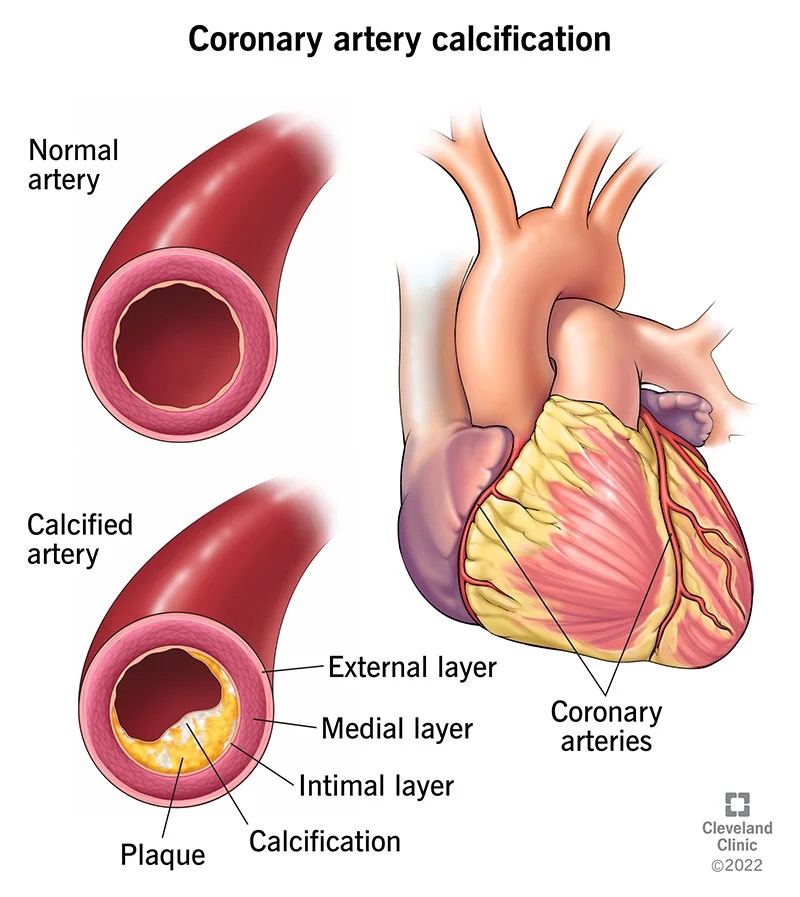

Side bar: CAC

CAC is a process by which calcium builds up in the coronary arteries of the heart, leading to hardening and a narrowing of the arteries. Calcification is commonly accompanied by the buildup of plaque, a process that contributes to atherosclerosis. CAC is measured using a technique known as cardiac computed tomography imaging, or CT. The presence of CAC, and increasing levels/progression of CAC, are associated with an increased risk for major cardiovascular events including heart attack and stroke, among others.

In MARC 1, athletes who reported the greatest volume of lifelong exercise — about 6 hours per week of exercise from age 12 onward — were more likely to have a CAC score > 0, indicating the presence of coronary artery calcification. The most-active group also had a greater prevalence of any type of plaque compared to the least-active group (who reported a lifelong exercise volume of around 1.5 hours/week).

In terms of exercise intensity, moderate- and vigorous-intensity exercise weren’t associated with the risk of CAC or plaque, but very-vigorous-intensity exercise was. The more time devoted to very-vigorous-intensity exercise each week, the greater the presence of CAC and plaque.

When looking at the type of plaque, however, something interesting stuck out.

The high-volume exercisers tended to have a lower amount of mixed plaques and more calcified plaques. Calcified plaques are known to be more stable and less likely to rupture. More calcified plaques in the heavy exercisers may translate to a reduced cardiovascular disease risk, despite the higher prevalence of atherosclerosis compared to the groups engaging in less exercise.

Other studies published since MARC seem to confirm the evidence presented therein.

A study from 2017 found that, compared to sedentary and age-matched controls, male masters endurance athletes had a higher prevalence of elevated CAC and coronary plaques, though similar to MARC, most of these plaques were calcified; the control group was more likely to have plaques that were of a mixed morphology.

A 2020 study provided evidence that the total volume of exercise is not related to the progression of CAC in middle-aged male and female endurance athletes.

A study published in 2021 including over 25,000 healthy adult men and women found that those who engaged in higher levels of physical activity were more likely to have CAC and a worse CAC progression compared to the least-active group.

There seems to be somewhat of a consensus. Athletes — especially those engaging in high volumes and/or intensities of exercise — may increase their risk for CAC and plaque development, but the type of plaques present in these athletes might not put them at an elevated risk for cardiovascular events.

However, questions remain as to whether maintaining a high level of exercise impacts the progression of atherosclerosis. Thanks to follow-up data from the MARC study, we now have an answer.