Physiology Friday #284: Can Low-Carb and High-Carb Pre-Exercise Meals Deliver Similar Performance?

A new study questions the dogma that carbohydrate oxidation is a critical determinant of endurance outcomes.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, and my book “VO2 Max Essentials,” can be found at the end of the post. You can find more products I’m affiliated with on my website.

“What should I eat before I work out or race?”

It’s one of the most common questions among endurance athletes, and also one of the biggest sources of pre-race anxiety. Despite everything we’ve learned about sports nutrition, we still don’t have a clear picture of the optimal pre-race meal. But carbs have always been at the center of the discussion (or rather, the plate).

It’s generally accepted among athletes that carbohydrates should make up most of the diet in the days and hours before a race (and, in many cases, throughout training). The rationale is straightforward—carbs support blood glucose levels and maximize glycogen availability, which becomes especially important when racing (high-intensity) or exercising for several hours. In fact, numerous studies have shown that consuming carbohydrates before exercise can significantly improve performance.

More recently, though, researchers have asked whether a lower-carbohydrate, higher-fat diet might also be compatible with endurance performance. It’s a fair question, given how rarely the high-carbohydrate paradigm in endurance sports is challenged. Carbohydrates are the obligatory fuel once exercise intensity rises above about 65% of maximal oxygen consumption—the very intensities associated with racing and high-intensity training. Fat oxidation, by contrast, is generally linked with lower-intensity exercise and is often considered an “inferior” fuel at higher intensities.

For this reason, substrate oxidation—whether the body relies more on carbs or fat—has traditionally been viewed as a key determinant of performance at higher intensities. Burning more carbs has been equated with running faster, while burning more fat has been thought to compromise performance.

But that assumption may not be entirely correct. What if substrate oxidation during exercise is less important for performance than we’ve long believed? If that’s true, then the contents of your pre-race or pre-workout meal may not matter as much as we think. Depending on who you are, this could be a major relief or just add more anxiety and confusion to the mix.

A recent study that included some notable researchers in the nutrition space set out to test the hypothesis that a low-carb, high-fat pre-race meal would produce equivalent performances during a 5k and 10k time trial compared to a high-carb, low-fat pre-race meal, despite these meals producing drastically different substrate oxidation profiles during exercise. The results are interesting, but I don’t quite think they “disprove” as much as the authors would like to believe. Let’s get into it.

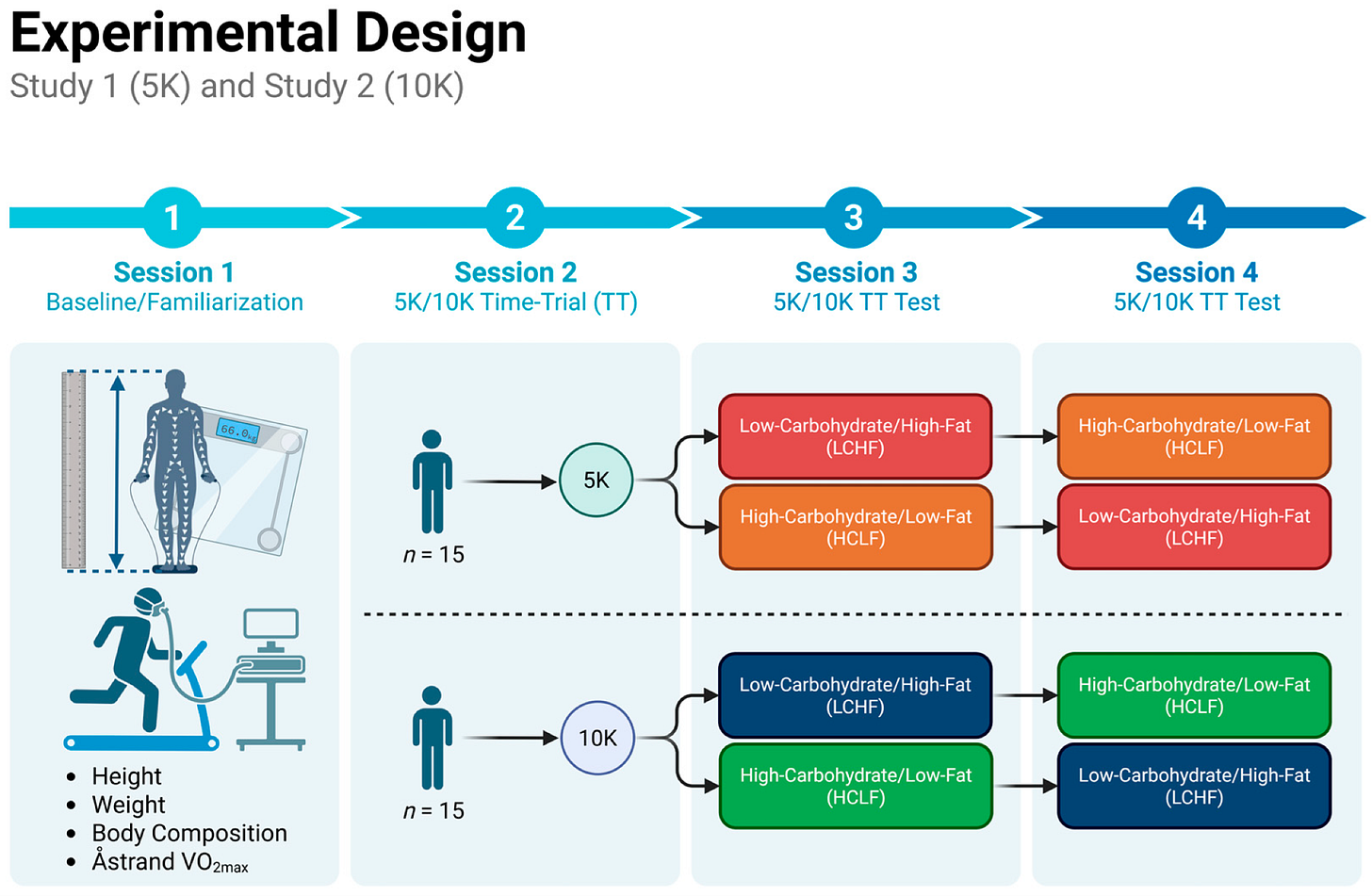

They recruited 30 experienced recreational runners (VO₂max ≥ 40, 10–30 miles of running per week, all on a “standard American diet”) and split them into two groups: one completed 5k time trials, the other 10k time trials (15 runners per group). Each runner went through baseline assessments (VO₂max test, familiarization, and a practice time trial) and, following that, two nutrition interventions.

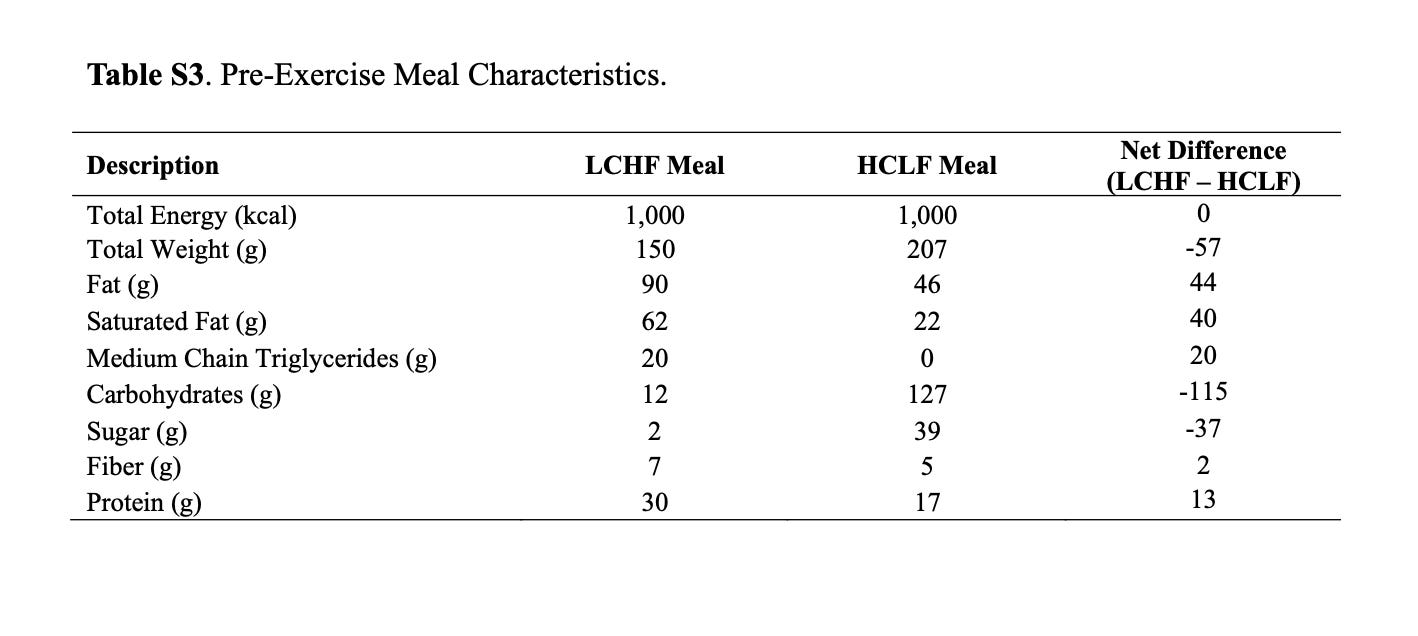

On two separate occasions, runners ate either a high-carb, low-fat (HCLF) pre-race meal or a low-carb, high-fat (LCHF) meal—I’ll refer to those as the high-carb and low-carb meals from now on. Both were ~1000 calories, matched for energy density and taste, but with opposite macronutrient profiles. The low-carb group ate something called a Keto Brick (which is, quite literally, a brick), and the high-carb group ate a Calorie Emergency food bar. Here’s the nutrient breakdown of each.

After an 8-hour overnight fast, they ate the meal, waited 3 hours, then ran their time trial (either 5k or 10k). The crossover design meant each runner did both conditions, with a 1-week washout in between.

The researchers measured time trial performance, substrate oxidation (fat vs carb use), blood metabolites (glucose, lactate, ketones), heart rate, and perceptual responses (RPE, fullness, thirst).

On the metabolic side, the meals did exactly what you’d expect.

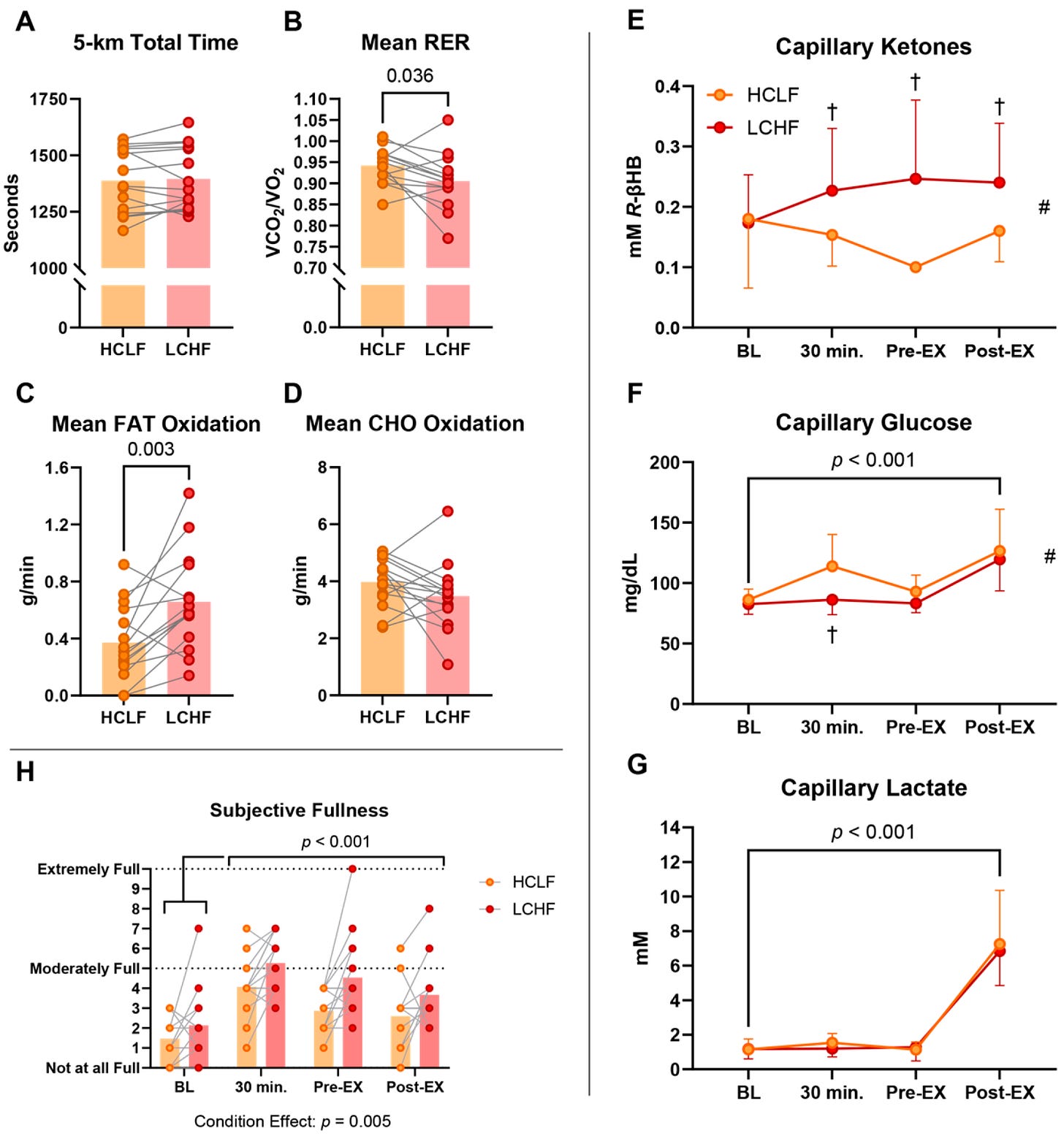

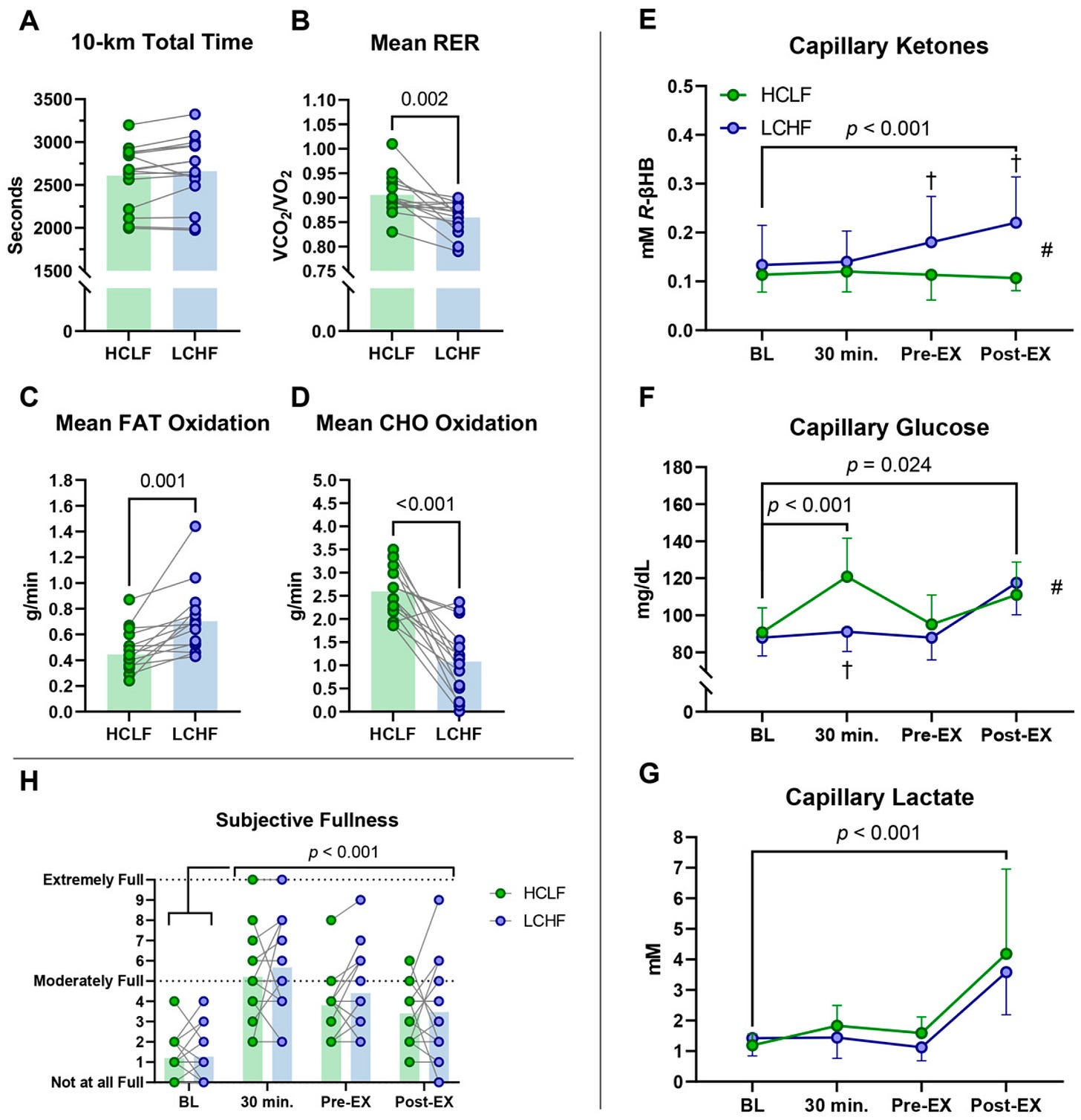

The low-carb meal boosted fat oxidation by 77% during the 5k (0.68 grams/minute vs. 0.37 grams/minute) and 58% higher during the 10k (0.70 vs. 0.44 grams/minute).

Carb oxidation was lower during the 10k time trial (by 68%; 1.06 vs. 2.59 grams/minute) but wasn’t different during the 5k time trial (3.49 vs. 3.98 grams/minute in low- and high-carb, respectively).

The respiratory exchange ratio (RER) dropped by 4–5% in the low-carb conditions, indicating a clear metabolic shift toward fat utilization.

The low-carb meal doubled circulating ketone levels (β-hydroxybutyrate), though levels were still below full nutritional ketosis, while the high-carb meal raised blood glucose by ~30% above baseline.

Here’s where it gets interesting. None of this metabolic shift translated into faster or slower times.

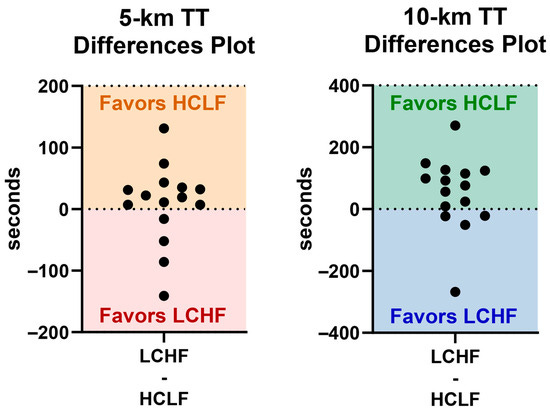

5k performance was nearly identical: 23 minutes and 18 seconds on average with low-carb vs 23 minutes and 6 seconds with high-carb.

10k performance was also very close: 44 minutes and 24 seconds with low-carb and 43 minutes and 30 seconds with high-carb.

The authors note this borderline trend favoring carbs in the 10k should be interpreted cautiously, but if you ask me, a nearly 1-minute difference in 10k performance, though not statistically significant, is worth noting.

So despite radically different substrate oxidation profiles, the time trials were nearly identical. There was, however, individual variability. And this is an important point. About 73% of runners ran faster after the high-carb meal, while 27% responded better to low-carb. The trend clearly favored overall faster times after the high-carb meal.

On the perceptual side, the low-carb meal was rated as more filling in the 5k group, though not in the 10k. RPE, mood, and affect were similar across conditions. Thirst increased with exercise but wasn’t influenced much by meal type. While these factors might not seem important, they’re strong indirect influencers of performance. How you feel affects how you run!

This study is consistent with the broader evidence from this same group of researchers. They’ve been testing the limits of low-carb fueling strategies for years. And while their findings have certainly made me think differently about sports nutrition, I think it’s far too early to claim low-carb and high-carb equivalence.

For example, in 2019, they published a crossover trial showing that six weeks on a low-carb, high-fat diet induced extremely high rates of fat oxidation (~1.5 g/min) but did not impair 5k performance in competitive recreational runners. In 2023, they reported similar findings in middle-aged men following isocaloric high- vs low-carb diets. Despite radically different fuel usage, exercise performance was again maintained. Fat oxidation rates reached world-class levels (~1.6 g/min, ~860 kcal/hr), yet time-trial results were unchanged. Even in a triathlete study published earlier this year, they showed that both low- and high-carb-adapted athletes could perform equally well—so long as some carbohydrate was ingested (~10 grams per hour) during the race to prevent hypoglycemia.

So the pattern here is that whether you load up on carbs or fats before short endurance events, the body adapts and delivers. Though I’ll note that there’s plenty of evidence to the contrary—adaptation to low-carb diets may reduce race performance in well-trained athletes (Louise Burke and colleagues are the pioneers in this research).

This was a great study, and I applaud the authors for executing it. But it’s not perfect, and some of the interpretations—especially those on social media—have been a bit too overzealous about what this means for low-carb nutrition.

The present study was acute—just two pre-race meals tested in recreational men. It tells me that what you eat before a race may not matter in the context of an otherwise well-formulated training diet that contains adequate carbohydrate. These results aren’t the “nail in the coffin” for carbohydrates. Far from it, and until I see something like this replicated in well-trained endurance athletes performing hours-long time trial events, my money is still on carbs.

It’s also potentially relevant to note that the study was funded in part by Keto Brick (what the participants ate in the low-carb arm of the meal), and several authors have ties to the low-carb/ketone world. To their credit, the results didn’t favor their narrative, which actually makes the findings more compelling.

My takeaway is this: if you’re gearing up for a middle-distance race, don’t overthink the macronutrient composition of your pre-race meal. What you eat consistently during training probably matters much more. And most importantly, go with what makes you feel confident and comfortable. Because at the end of the day, peace of mind may be the best fuel.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of gummies (and yeah…their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands), flavored creatine monohydrate single-serve packets, and a daily performance greens gummy (my personal favorite). They’re giving my audience 20% off their order. So stock up!