The Profound Link between Sleep and Cardiovascular Aging

Give your heart a rest.

There are several modifiable risk factors for human health.

The three most important are exercise, diet, and sleep. Of course, several others exist, including mental health, relationships, abstaining from smoking and alcohol, etc.

We’re here to talk about sleep.

Most people don’t get enough sleep. Major health organizations recommend at least 7–9 hours of sleep per night for optimal health — a target that nearly 50% of people miss.

Sleep duration and quality also decline with age; older individuals report a diminished ability to fall and stay asleep. This might have to do with age-related changes in circadian biology, including a dampening of the sleep–wake rhythm and an earlier shift in their circadian clock. This is why older adults tend to wake up earlier and get extremely tired in the early evening (by a show of hands, who can relate?)

The importance of sleep has not gone unrecognized by the public or by science. In fact, last year, the American Heart Association (AHA) added sleep to their “Simple 7” components of cardiovascular health (making it the “Essential 8”). This was, in my opinion, a major step in the right direction. Sleep and heart health are closely related.

All organisms on earth sleep — it’s a biological imperative.

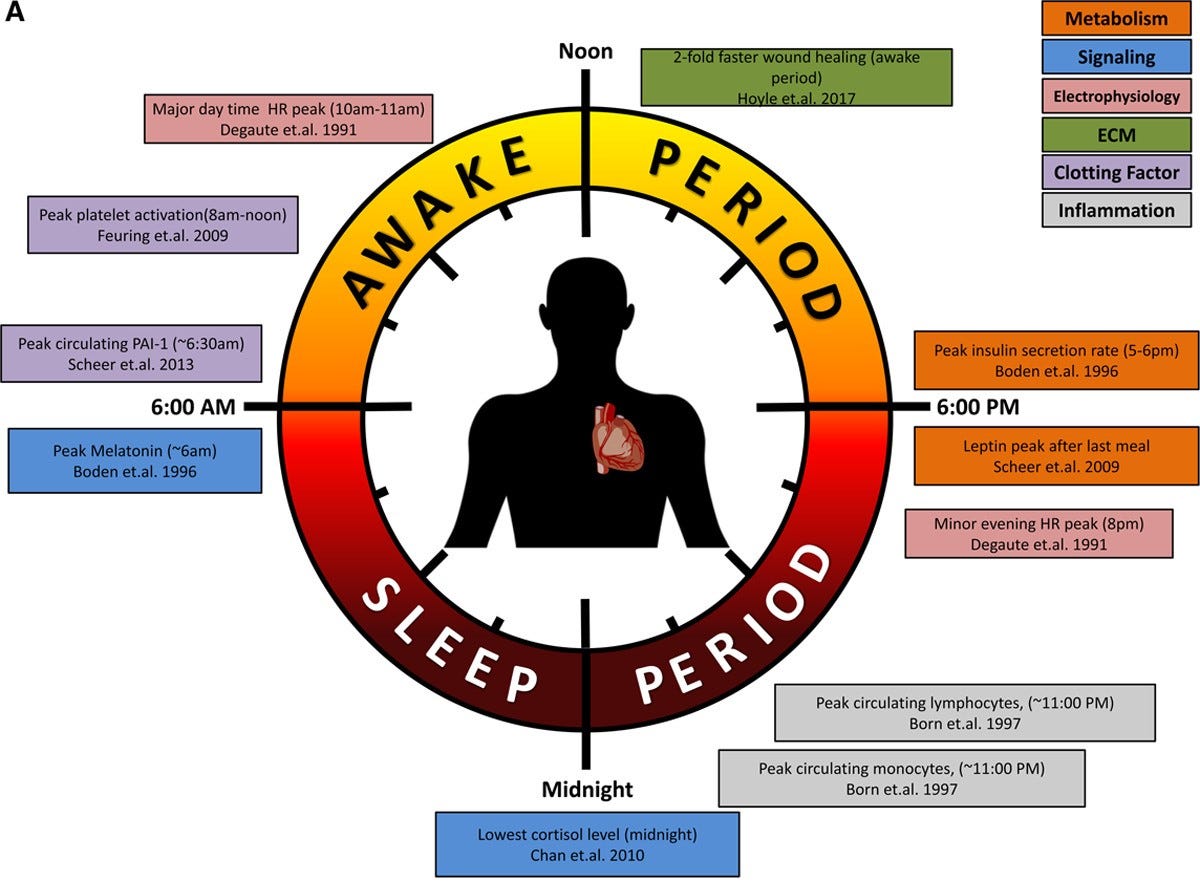

The right amount of sleep at the opportune time is crucial for our body’s maintenance of homeostasis and the function of our circadian rhythm. Our endogenous circadian rhythms synchronize our body’s physiology with the external environment — feeding, fasting, and sleep are all part of this cycle.

Our heart is not exempt from these day–night shifts. Circadian clocks are present in cardiac muscle and endothelial cells in our blood vessels. These clocks regulate heart rate, blood pressure, and endothelial function across the 24-hour day. When we wake up, blood pressure rises, our platelets are better at clotting, and levels of cortisol and other “weakness-promoting” hormones begin to rise.

The morning cardiovascular rhythm primes our body for action.

At night, heart rate, blood pressure, and blood clotting ability drop, as do levels of cortisol. These allow our cardiovascular system (and us) to rest easily.

Given the role of sleep in regulating cardiovascular health and function, it’s not surprising that poor sleep quality and short sleep duration are associated with greater morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD) — which is currently the leading cause of death around the world.

How does sleep lead to the progression of CVD?

One of the candidate mechanisms may be something known as endothelial function, which refers to the ability of our blood vessels to relax (vasodilate) and contract (vasoconstrict) in response to the body’s changing demands in blood flow and oxygen.

Endothelial function is also crucial for blood-pressure regulation, brain health, and normal circulation.

Endothelial dysfunction indicates poor blood vessel function, and it’s the initiating step in the development of atherosclerosis, arising before any other detectable signs and symptoms.

Endothelial function also holds prognostic value. Laboratory-measured endothelial function in the heart (i.e., the coronary arteries) or blood vessels in the arm (i.e., the brachial or femoral arteries) can predict your heart attack and stroke risk.

In fact, endothelial dysfunction is considered to be a “hallmark” of cardiovascular aging.

Vascular function declines with age, a process that poor sleep might exacerbate.

While this hasn’t been directly studied, sleep deprivation as a risk factor for premature cardiovascular aging is a plausible hypothesis,

In order to link sleep deprivation to CVD and vascular aging, we can look at the experimental evidence on how a lack of sleep impacts our heart and blood vessels, an area that has been devoted a significant amount of research attention, which myself and colleagues synthesized in a recent systematic review. Here were some of our findings.

Sleep deprivation and endothelial function

When it comes to the observational literature, it’s quite clear that insufficient sleep is associated with lower endothelial function. In cross-sectional studies, adults who sleep less than 7 hours each night have lower microvascular endothelial function (a measure of small-vessel function) compared to adults who sleep more than 7 hours each night.

In experimental studies, total sleep deprivation — going without sleep for 24 hours or more — impairs macrovascular and microvascular endothelial function in adults.

Even restricting sleep to 4–5 hours per night for up to 8 nights reduces endothelial function in several blood vessels in the body.

An interesting area of the literature involves shift workers — people who work outside of a normal 9–5 and typically partake in overnight work shifts. When comparing shift workers to non-shift workers, the shift workers consistently demonstrate worse endothelial function. When you measure endothelial function in someone before and after a night shift, it's worse after, indicating a direct effect of night shift work on cardiovascular function.

While not all studies show that restricting sleep decreases endothelial function, this is a pretty consistent finding across studies. It’s important to note that many of these studies were conducted in younger healthy individuals, not people with cardiovascular disease or adults older than 65 years of age. For that reason, we can only speculate that sleep deprivation may have similar or worse effects in the setting of aging and disease.

How might sleep deprivation lead to endothelial dysfunction? This is an area where the literature isn’t as dense, but there are some plausible mechanisms.