The Science of Semaglutide for Weight Loss: Mechanisms, Effectiveness, and Causes for Concern

Are anti-obesity drugs the solution to an epidemic of expanding waistlines?

Ozempic is all over the news lately.

This weight-loss drug (or weight loss “jab” as it’s referred to) has gained popularity not only among individuals with obesity and diabetes — for whom it’s indicated — but also among celebrities and the general population — who see it as a quick fix to lose a few pounds for the summer. Many celebrities are outspoken about their liberal use of the drug.

The use of Ozempic among those without a clinical need is somewhat controversial — some claim it’s cheating to use a drug to fix a weight problem rather than “do it the hard way” using diet, exercise, and other lifestyle interventions.

I’ve tweeted my opinions about the Ozempic criticisms before. Generally, I don’t care how someone chooses to lose weight. Of course, sustainable weight loss via lifestyle change is preferred, and there’s evidence to indicate that someone who loses weight with Ozempic will regain that weight once they stop. It’s probably not the ideal way to lose weight among the myriad options at one’s disposal.

But there’s no denying that weight-loss drugs like Ozempic can be helpful and effective for those in need. We certainly need to learn more about the long-term metabolic and neuropsychological side effects of Ozempic and other similar drugs if they are to become mainstream treatments for obesity and diabetes — two conditions whose rates are rising around the world.

In lieu of an opinionated take on the ethical and moral aspects of so called “anti obesity drugs” like Ozempic, in this post, we’ll take a look at the science behind weight-loss drugs, their effectiveness, and some concerns about their use.

GLP-1 agonists: how they work 💉

Ozempic and its relatives (some which fall under the broad name Semaglutide) belong to a class of medications known as GLP-1 agonists.

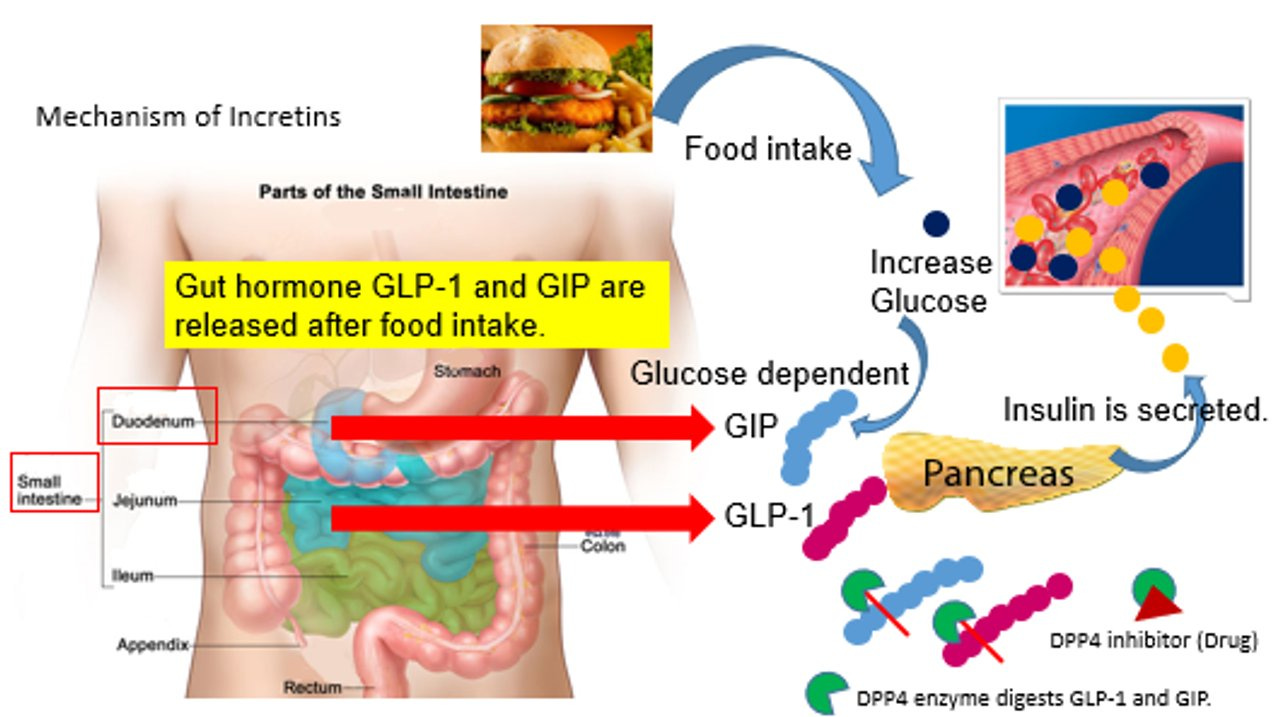

GLP-1 (which stands for glucagon-like peptide 1) is a hormone that’s released from cells in our intestines and colon after we eat.

When GLP-1 binds to its receptor, it stimulates the release of insulin (the blood-glucose-lowering hormone) and inhibits the release of another hormone called glucagon (the blood-glucose elevating hormone) by the pancreas. Since GLP-1 receptors are located in the brain, intestines, and elsewhere in the body, GLP-1 binding can increase feelings of fullness and satiety, reduce hunger, and subsequently decrease food intake.

Synthetic GLP-1 agonists such as Semaglutide (e.g., Ozempic) mimic the effects of GLP-1.

Not only that, they have a longer half-life in the body than GLP-1, making for longer-lasting therapeutic effects (the half life is how long it takes for half the amount of a drug to be metabolized by the body).

The half-life of Semaglutide can range from 155 to 184 hours, while the native hormone lasts only a few minutes before being degraded. Thus, Semaglutide can be taken (by injection) just once a week.

GLP-1 agonists, when combined with a reduced-calorie diet and regular physical activity, can help with weight loss, and they’re rarely prescribed outside of the context of additional lifestyle changes, and likely wouldn’t be effective in isolation.

GLP-1 agonists work because they help someone to eat less, plain and simple. There’s not much evidence to indicate that they have any effects on energy expenditure per se. These effects on hunger and fullness are mediated by the drugs’ impact on the brain, stomach, and pancreas.

There are other weight-loss drugs that work via different mechanisms to help with weight loss — some prevent fat from foods from being absorbed by the body, some decrease appetite and cause feelings of fullness, and some help to control cravings.

How effective are GLP-1 agonists? ⚖️

A series of clinical trials on Semaglutide (known as the STEP trials) have reported that 68 weeks of the drug taken in a dose of 2.4 mg once per week reduced body weight by 9.6%–17.4% (up to 12.5 kg or 27.5 lb) in adults with obesity or who were overweight and had at least 1 comorbidity. That’s a good amount of weight loss.

Semaglutide is better than other anti-obesity medications, for which weight loss in the range of 2.6–8.8 kg (5.7–19.4 lb) has been reported, but less effective than newer GLP-1 agonists like Terzepatide; a 9.2 kg/20.2 lb greater weight loss was reported with once-weekly Terzepatide vs. Semaglutide.

Semaglutide and other GLP-1 agonists may also improve cardiovascular disease risk factors