Time-restricted Eating Increases Your Risk of Cardiovascular Death? Don't Buy the Headlines.

Lies, damned lies, and nutritional epidemiology.

When I read a news headline about science, I try to first apply Hanlon’s razor: not attributing to malice what can likely be explained by incompetence.

This proves to be difficult almost daily, increasingly so in the age where clickbait sells.

This week is no different.

On Monday, several news outlets posted headlines regarding a new “study” with the alarmist claim that “8-hour time-restricted eating linked to a 91% higher risk of cardiovascular death.”

As I write this, a news clip on the “new dangers of intermittent fasting” just finished airing on the television. I almost threw my remote.

Not surprisingly, the social media hype around these headlines and the study itself was immediate and strong, and I saw a bit of contrasting perspectives appearing on X and elsewhere.

On the one hand, I noticed a handful of clinicians who reposted the link to the study with the headline in-tact — presumably in support of the findings. On the other hand (and more commonly), I saw health-minded individuals, experts, and scientists alike chiming in about the likely insignificance of the study.

Given my extensive research on the topic of time-restricted eating (TRE), I was part of the latter camp. Here’s why.

What did (or didn’t the study) show

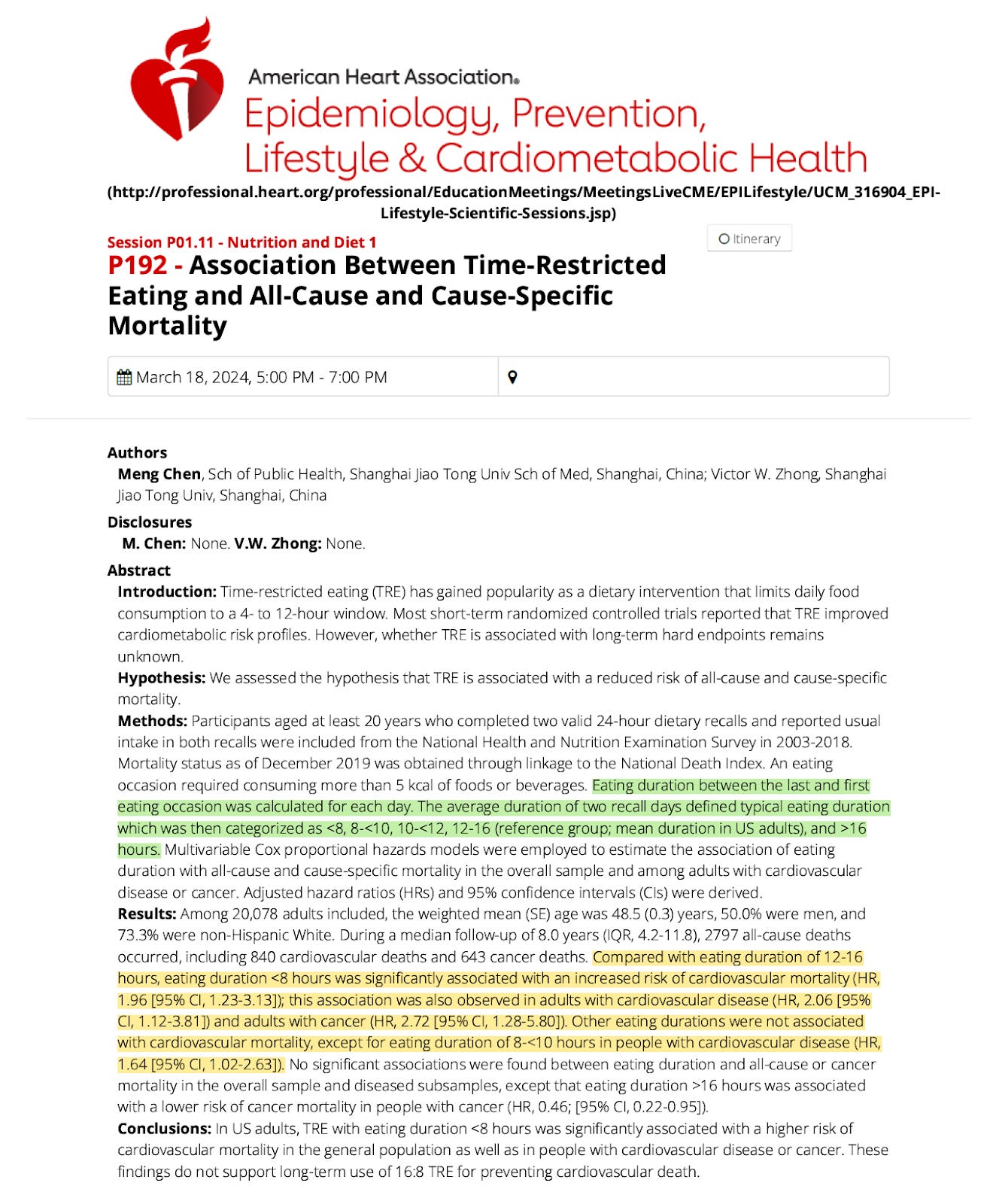

The first thing to mention is that this was not a peer-reviewed study published in a scientific journal. The “study” was a scientific abstract published as part of the American Heart Association’s annual conference on Epidemiology, Prevention, Lifestyle & Cardiometabolic Health.

Scientific abstracts are presented after the data from a study are collected and analyzed but before they’ve undergone peer review. As such, an abstract lacks crucial information about the study methods, statistics, and other details. Think of it as a small snapshot of a study meant to be a “teaser” for the peer-reviewed publication.

This doesn’t mean that the results or methods are invalid, but the results should be interpreted with caution, for now.

Speaking of the abstract…

For the study, the researchers investigated the hypothesis that TRE was associated with a reduced risk of all-cause and cause-specific (i.e., cardiovascular disease and cancer) mortality. This is a sound hypothesis based on the extensive literature showing health benefits of TRE in the short term.

To do this, they analyzed data from over 20,000 participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2003 and 2008. Briefly, NHANES is a large cohort study that gathers information on adults in the U.S. regarding demographic, socioeconomic, dietary, and health-related factors collected via surveys and physiological measurements/lab tests.

Specifically, the participants completed two 24-hour dietary recalls, from which their meal times (least eating occasion of the day and first eating occasion of the day) were gathered. From this information, each participant’s daily eating duration could be calculated and grouped into one of the following patterns:

8-hour eating duration (“16:8 TRE”)

8–10 hour eating duration

10–12 hour eating duration

12–16 hour eating duration

>16 hour eating duration

The 12–16 hour eating duration was used as the reference group, as this represents the average eating duration of adults in the U.S.

This brings up our second problem: the study did not examine TRE per se. Studying TRE would mean assigning participants to a TRE group or a control group in a randomized controlled study, allowing them to adhere to the diets for [X] amount of time, and comparing the health of the participants at the end.

That’s not what’s done with NHANES data. Simply, the NHANES data are just a reflection of the participant’s self-reported eating duration assessed retrospectively — they’re not assigned to a diet and then followed, but rather, put into a diet group based on their reported habits.

Putting aside the issues of recall bias, it’s impossible to tell if the participants were actively practicing 16:8 TRE (not likely) or whether 8 hours just happened to be their natural eating/fasting pattern (more likely).

Furthermore, it’s a big leap to generalize information from two 24-hour dietary recalls to someone’s chronic dietary habits.

Do you eat at the same time every single day? Do you even remember the exact time you had your last and first “eating occasion” on any particular day (an “eating occasion” means consuming more than 5 calories of food or beverages…so…almost anything)? Probably not. I’m not the only one who thinks food questionnaires are next to useless.

Back to the study in question. When the researchers compared the reference group (people with a 12–16 hour eating window) to the other groups, they found that the people with an eating window of 8 hours or less (“16:8 TRE”) had a 91% greater risk of dying from cardiovascular disease. Adults with cardiovascular disease and cancer had a 107% and 204% greater risk, respectively, when they had an 8-hour eating window.

So, eating for less than 8 hours each day increases your risk of dying from cardiovascular disease. But of course, to quote one of the study authors: “Although the study identified an association between an 8-hour eating window and cardiovascular death, this does not mean that time-restricted eating caused cardiovascular death.”

Of course it doesn’t mean that.

This conclusion is easy to support knowing everything we do about the benefits of TRE.

The cardiometabolic benefits of TRE

A number of studies have compared the effects of TRE to traditional dietary restriction, also known as calorie restriction (CR). Both interventions have benefits, and sometimes TRE offers unique benefits to CR. Hence why it’s often recommended as a weight-loss strategy.