VO2 Max Essentials Part III: How Trainable is VO2 Max?

Are the health benefits of a higher aerobic fitness available to all?

In previous posts from this series, we’ve discussed the factors that determine and limit VO2 max, as well as the importance of VO2 max — among other variables — for successful endurance performance.

However, there’s a debate in exercise physiology about VO2 max. The debate isn’t about whether it’s important for health and performance, but rather, whether there’s actually anything we can do to significantly improve our VO2 max.

In other words — are we born with a predisposition to have a higher or lower VO2 max? Are those with a low VO2 max destined to a lifetime of poor aerobic fitness?

VO2 max trainability

Trainability refers to an individual's ability to improve their VO2 max. The significance of trainability extends beyond the realm of sports, as it has potential implications for public health.

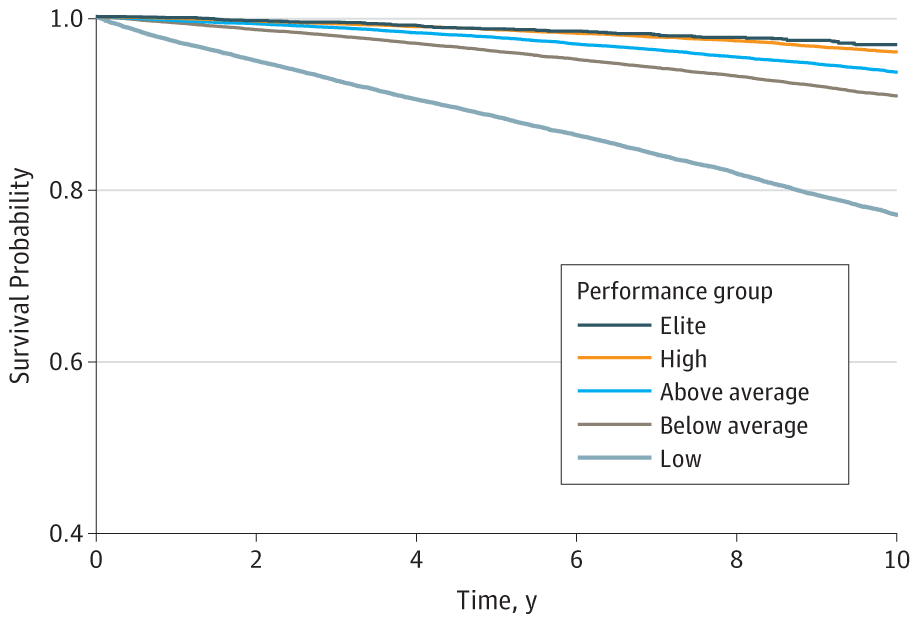

Indeed, research has shown that higher VO2 max levels are associated with a reduced risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. In fact, every 1-MET increase (3.5 ml/kg/min) in VO2 max is linked to a 15% decrease in all-cause mortality. Plenty of other data suggest that, the fitter you are, the longer you’ll live.

However, the concept of trainability raises important questions. If some individuals do not experience an increase in VO2 max despite training, do they still receive the same mortality benefits? Should different training programs be designed for such individuals, or should they forget about exercise altogether? Additionally, do current physical activity and exercise guidelines adequately ensure that most people can increase their fitness?

This last point is important, considering that it has been found that high levels of fitness may be more protective against cardiovascular and all-cause mortality compared to physical activity alone.

This highlights the importance of understanding and maximizing trainability to enhance the health benefits of exercise. Targeting VO2 max improvements may be one of the most potent risk-reduction strategies.

It’s crucial to differentiate between training and physical activity. Exercise training is a structured program aimed at improving physical capacity. Physical activity is more “incidental”, though adaptive responses can also occur through leisure time or occupational physical activity.

However, it’s unlikely that significant aerobic fitness benefits can be derived from physical activity alone, at least for most people. Thus, it’s important to have a well-designed training program if we want to optimize VO2 max benefits.

Are training prescriptions too weak?

Regarding training, the intensity and frequency, as well as the duration of the training sessions are important factors to consider. Current public health guidelines recommend moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity for around 150-300 minutes each week. Studies have shown an average increase in VO2 max ranging from 15% to 20% can occur through guidelines-based exercise programs.

However, more frequent or intense training can lead to even higher increases in VO2 max, averaging around 25% to 30%. It is worth noting that the increase in VO2 max doesn’t appear to be influenced by factors such as baseline VO2 max, race, sex, or age (up to middle age). This suggests that individuals of various backgrounds and fitness levels can experience improvements in VO2 max through training, though certainly at the highest levels of fitness, there is less room for improvement.

Interestingly, some individuals may respond minimally to guidelines-based training programs, demonstrating limited or no trainability. Such individuals are often called “exercise non-responders.”

Approximately 10% to 20% of subjects in a study known as the HERITAGE study showed limited trainability, suggesting that the effectiveness of a standard training program may vary among individuals. Furthermore, some subjects may not experience improvements in other health-related factors such as blood pressure, blood lipids, and blood glucose in response to standard exercise programs.

However, the concept of adverse or non-responders to risk factors has been challenged, as many of the protective effects of fitness and physical activity on health operate through mechanisms not captured by traditional risk factors. In other words, whether one “responds” or not to exercise depends entirely on the outcomes measured.