What Running a Marathon Does to Your Body

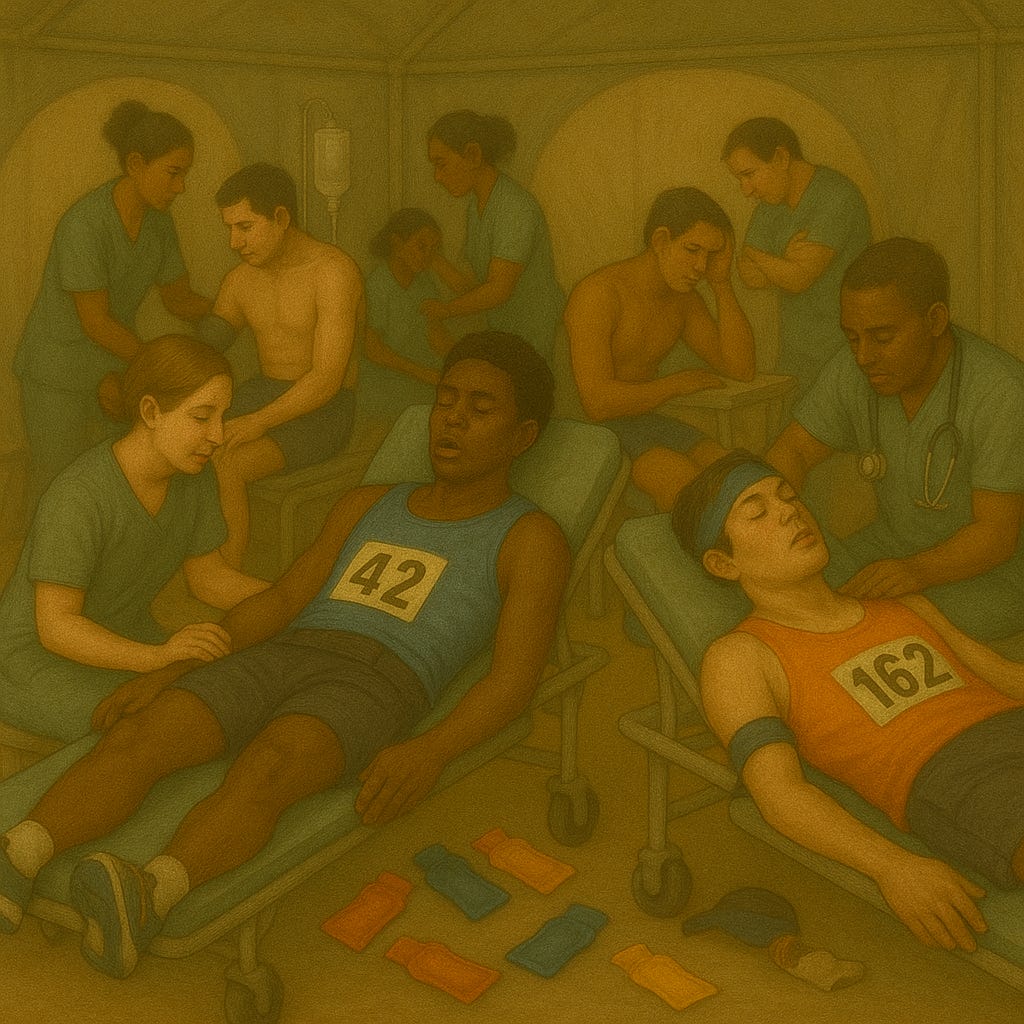

It isn't good...

For years, researchers have known that marathons cause temporary spikes in biomarkers of organ stress—things like creatinine (a kidney function marker) and gut cell damage. But most studies haven’t measured these changes before and after a marathon under real-world race conditions. And the role of hydration—or sex differences—has remained murky.

A new st…