Busting common myths about caffeine

Stop delaying your morning coffee.

Caffeine — it’s one hell of a drug.

Also known as 1, 3, 7-trimethylxanthine, caffeine is one of the most well-understood substances in terms of its effect on our brain and body. It’s also one of the most used drugs in the world.

For most people, caffeine has an ergogenic (performance-enhancing) effect. It can help increase your strength, endurance, and reaction time, among other benefits.

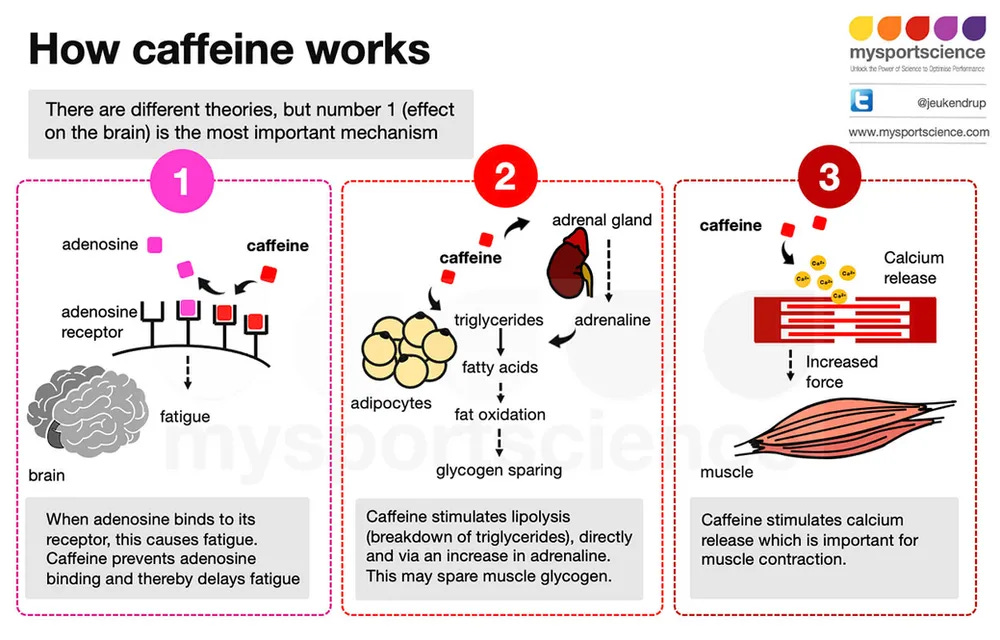

Exactly how caffeine improves performance is not quite clear, but might involve improvements in muscle contractile function and increased fat oxidation.

Caffeine acts on the brain to make us more alert and less sleepy. Caffeine is an adenosine receptor antagonist — it binds to adenosine receptors and blocks the binding of adenosine. Normally, adenosine is a molecule that builds up throughout the day and makes us feel sleepy. When it can’t bind to its receptors, we remain awake and alert.

Caffeine levels in the body will typically peak around one hour after ingestion, give or take. The half-life of caffeine — the amount of time it takes for the body to metabolize ½ of the caffeine you’ve ingested — is around 5 hours.

In other words, if you consume 300 mg of caffeine at noon, there’s about 150 mg still in your system at 5 p.m. However, there’s a large individual variation in caffeine metabolism that can be attributed to several factors including genetics, food intake, the use of medications, and certain health conditions.

It probably comes as no surprise that we all respond differently to caffeine. Some people can tolerate an espresso one hour before bed while others have to abstain from noon onward to prevent caffeine from impacting their sleep.

There are also several misconceptions — let’s call them “myths” — about caffeine/coffee. Some have originated from popular podcasts while others are probably remnants of things your grandmother warned about.

In a new paper published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition,1 some savvy experts looked at the evidence on some common myths about caffeine. I’ve chosen a few of my favorites to share with you today.

Myth #1: Caffeine dehydrates you

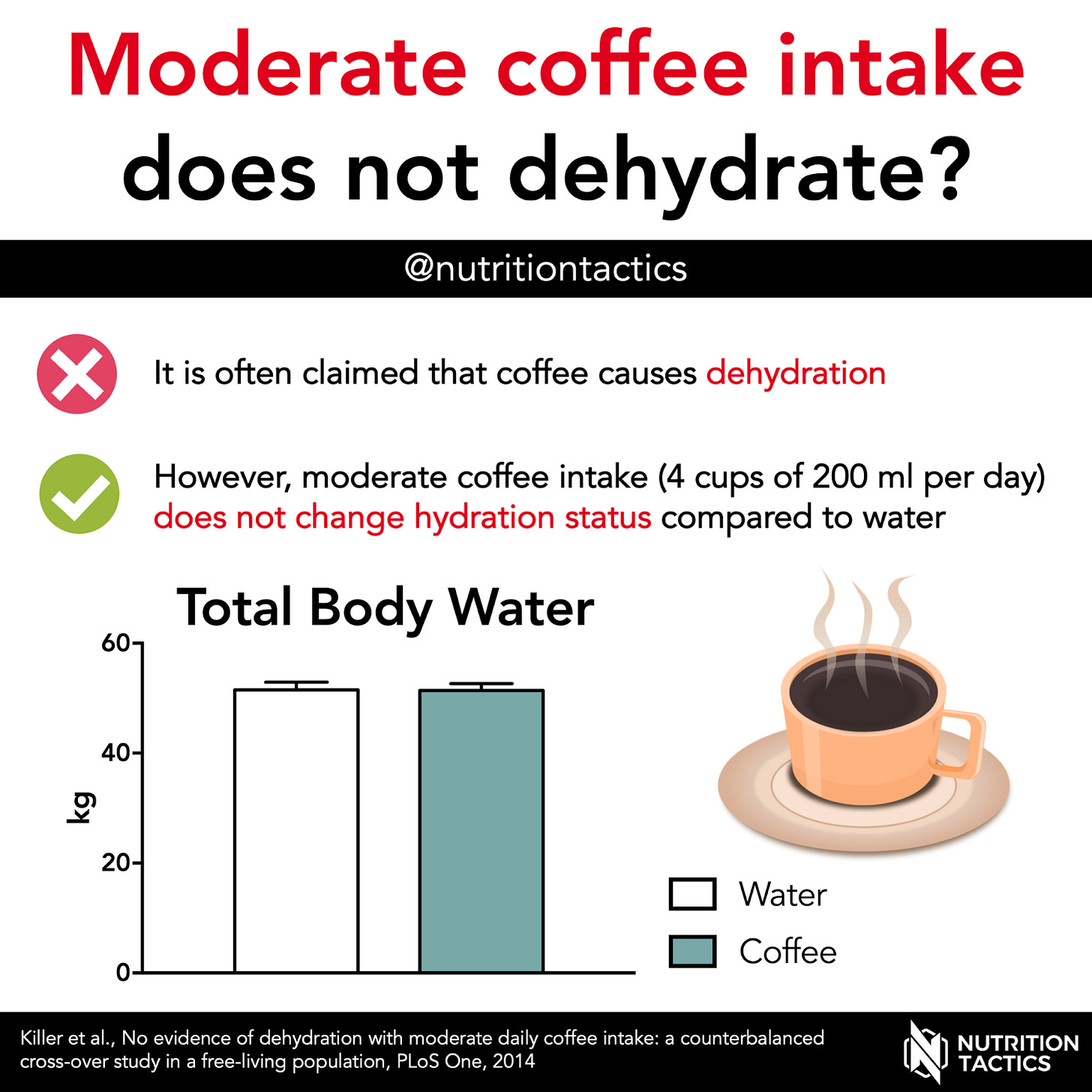

This is certainly one that you’ve heard before. It’s something that I hear on an almost daily basis. The myth originates from the fact that some studies have shown that caffeine can act as a diuretic — it increases urine production — and thus promote fluid loss and dehydration.

This idea may have gained traction after a 2003 paper which observed that a caffeine dose of 300 mg or more promoted urine output in people who had been deprived of caffeine for a few days to a few weeks. Hardly the nail in the coffin for avoiding caffeine. The effects of a high dose (500 mg or more) of caffeine on urine output are also somewhat well established.

But recent evidence shows that consuming a dose of caffeine typically present in a cup of coffee or tea or a can of soda — 30 mg up to 300 mg — does not promote an increase in urine volume in regular caffeine drinkers. However, a caffeine dose of 500 mg or more may promote diuresis. But who’s consuming this much in a single sitting?

Your habitual caffeine intake might be an important factor here because there does seem to be a tolerance to caffeine’s diuretics effects that develops over time. Someone who is caffeine naive may experience a diuretic effect after a moderate to high caffeine dose, but someone who is used to consuming ~300 mg at a time probably won’t.

What about during exercise? Does caffeine influence urine output or fluid retention (i.e., hydration) during exercise, particularly in the heat?

Similar to the effects of caffeine at rest, caffeine doesn’t appear to have a dehydrating or diuretic effect during exercise as long as an appropriate hydration strategy is followed. If you hydrate with a 16-ounce carbohydrate and electrolyte drink during exercise, adding caffeine won’t diminish its effects on hydration. This is an important point. If you take caffeine as a pill, for example, and don’t drink adequate fluids, then it may dehydrate you compared to no caffeine.

But for most people, caffeine consumption is concomitant with fluid ingestion, especially during exercise when we might drink a pre-workout beverage, cup of coffee, or energy drink. The diuretic effects of caffeine (at rest or during exercise) don’t outweigh the 12–16 ounces or more of fluid ingestion that promotes a net increase in hydration.

There’s also the fact that caffeine improves exercise performance. If it truly were dehydrating, we might expect moderate to high caffeine doses to reduce performance, but this doesn’t seem to be the case.

To conclude: factors like your sweat rate, the environment, and genetics have much more of an influence on your hydration status at rest and during exercise than caffeine.

A dose of caffeine up to 300 mg does not “promote dehydration” and you shouldn’t avoid caffeine before exercise for this reason. If you’re taking a caffeine pill or caffeinated gum, just be sure to drink some water or other beverage with it.

Myth #2: Habitual caffeine consumers don’t experience the performance-enhancing effects of caffeine

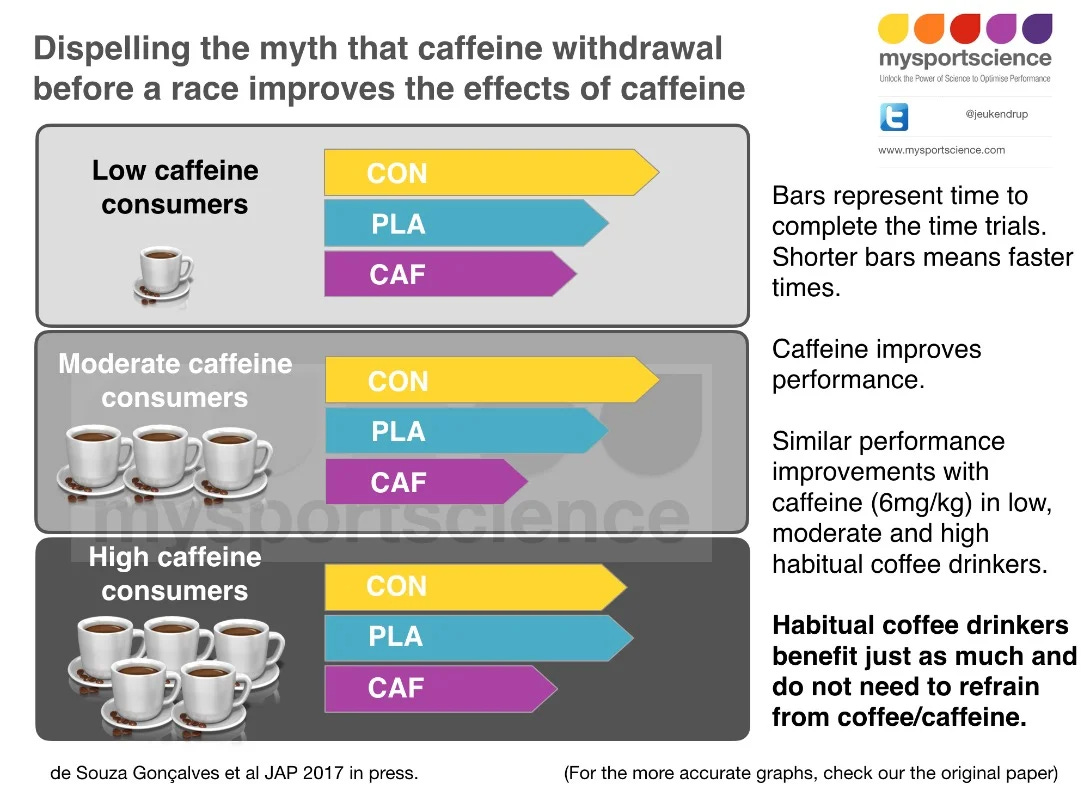

As with most drugs, we can develop a tolerance to caffeine. If we drink a lot of caffeine for a long period of time, or body won’t respond to the same dose of caffeine with as much vigor. We need more to achieve the same desired effect.

This has led to the theory that for a regular caffeine consumer to experience a performance-enhancing benefit of caffeine, they need to abstain from caffeine for a few days to a week.

For the most part, this doesn’t seem to be true. Habitual caffeine consumers may experience a diminished effect of caffeine on performance, and they may need a higher dose (i.e., 6 mg per kilogram of body weight) to achieve an ergogenic effect. If I regularly consume 180–200 mg of caffeine, then I might need 360–400 mg if I want a performance boost on race day.

One of the biggest issues plaguing the research and preventing us from having clarity about the effects of habitual caffeine intake is that studies poorly characterize (or don’t characterize at all) what “habitual caffeine consumption” means.

Someone can be a habitual caffeine consumer by drinking 50 mg of caffeine in coffee daily but also by drinking 300 mg of caffeine in an energy drink each morning. These are obviously two different tiers of habitual caffeine consumption. Research hasn’t standardized caffeine doses well enough to make firm conclusions.

Despite the lack of standardization, the current consensus is that habitual caffein intake does not negatively impact the performance improvements due to caffeine consumption. You can have your coffee and drink it too.

The best strategy is to double your typical daily caffeine dose before an important race or athletic event. This will likely lead to the biggest performance boost.

Myth #3: Caffeine is bad for your heart

Caffeine is a stimulant with acute effects that (can) include an increase in heart rate and blood pressure. For people with cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension, this could be an issue.