Physiology Friday #178: Can Exercise Rescue Mood and Cognitive Function from the Effects of Sleep Deprivation?

Working out has mental benefits when we’re well-rested, but what about when we’re not?

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter!

In case you missed it, last week I released my first eBook, “VO2 Max Essentials.” You can find information on it, including where to purchase, in this post.

One more announcement. Examine.com (the BEST site on the internet for unbiased health & nutrition information) is having a summer sale! Right now, you can take 20% off of an Examine+ membership and enjoy all of the content they have to offer on supplements, diet, exercise, and more.

Exercise improves our mood, makes us cognitively sharper, and has overall benefits for well-being. A healthy sleep habit can do the same.

A lack of sleep, on the other hand, tends to diminish mood and cognitive function (as does a lack of exercise, if you’re anything like me).

Levels of sleep have seemed to decline progressively over the years, and despite the recent rise in the interest for smart mattresses and biohacks for better sleep, many people still don’t get enough of it.

We’re all not going to sleep 7–9 hours every night. Life happens (we just had our first child, so don’t I know!) — consistency is what matters, not the odd 1-2 days off schedule.

Nonetheless, even a few nights of inadequate sleep can have devastating consequences for mood, alertness, and cognitive function. Just a single night of sleep restriction reduces our insulin sensitivity to the levels of someone with type 2 diabetes.

Can we do anything to counteract the physiological and psychological impact of poor sleep?

In the last few years, some cool studies have been published on the protective effects of exercise during sleep restriction. I summarized this evidence in a previous post.

Some of the most interesting data (imho) has shown that exercise during sleep restriction (4 hours/night for 5 nights) helps to maintain glucose tolerance and myofibrillar protein synthesis, which is otherwise impaired during sleep restriction.

Tl;dr: poor sleep harms metabolic function. But exercise can come to the rescue.

What is less well known is whether the cognitive deficits experienced during sleep can also be partially or completely rescued by performing exercise.

This question was investigated in a recent study published in the Journal of Sleep Research.1

24 healthy young men (average age of 24) were randomly assigned to one of three different conditions: normal sleep (NS), sleep restriction (SR), or sleep restriction + exercise (SR + EX).

During the 8-day experimental portion of the study, participants in the NS group received 8 hours in bed each night, while participants in both of the SR groups received only 4 hours in bed, after a 2-day baseline sleep period, during which all groups received 8 hours time in bed.

In addition, participants in the SR + EX group performed 3 sessions of high-intensity interval exercise (HIIT) on the 4th, 5th, and 6th days of the experiment. Each HIIT session involved 10 x 60-second intervals performed at 90% of the participants’ peak heart rate.

Lighting, physical activity, and diet were well-controlled and standardized in all groups.

The primary outcomes measured throughout the study included a test of psychomotor vigilance (behavioral alertness and reaction time), subjective sleepiness, well-being, and mood. Sleep-related variables were also assessed nightly.

Results

Per the study design, participants in the SR and SR + EX groups received less sleep than their baseline and compared to the NS group — just under 4 hours each.

Subjective sleepiness in the morning/evening (assessed using a questionnaire known as the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale, or KSS) increased on days 5, 7, and 8 in the SR group and on days 5, 6, 7, and 8 in the SR + EX group; levels of sleepiness didn’t change in the NS group. Sleep efficiency — a measure of sleep quality — was unchanged in all groups.

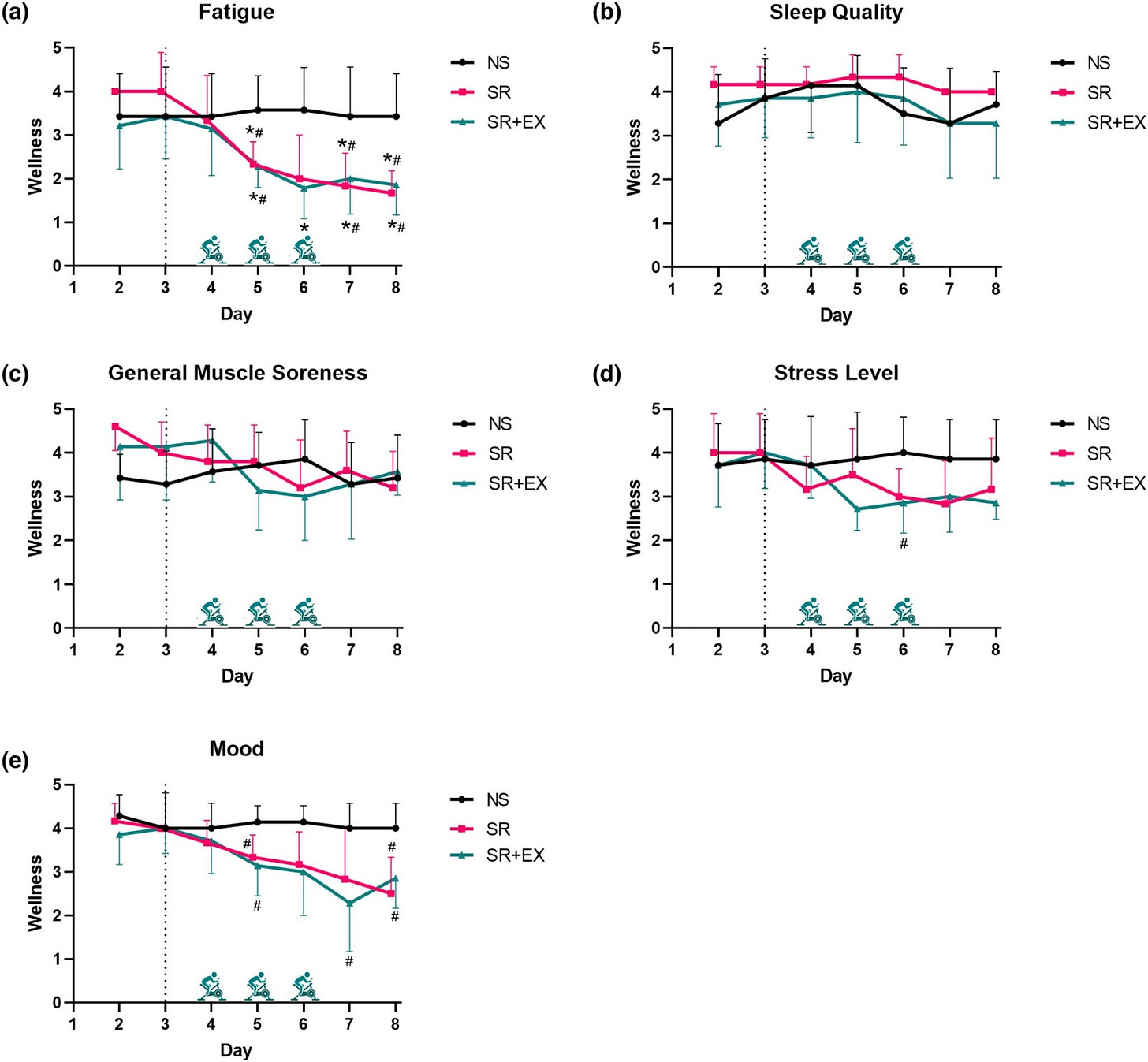

Levels of fatigue increased and mood decreased in the SR and SR + EX groups on days 5–8, while stress increased in the SR + EX group on day 6.

Total mood disturbance (including tension, anger, fatigue, depression, vigor, and confusion) was increased after the intervention in both of the SR groups.

During the test of psychomotor vigilance, both the SR and SR + EX groups had increased (worse) average reaction times, though their fastest and slowest reaction times didn’t change.

In contrast, none of the above outcomes, including mood, psychomotor vigilance, and fatigue, changed in the NS group throughout the study. Furthermore, none of the outcomes were different between the SR and SR + EX groups — in other words, they both experienced similar levels of cognitive/mood impairment during the study.

In summary, cutting sleep time in half for five consecutive nights impairs mood and alertness, and increases fatigue, effects that don’t seem to be mitigated by performing exercise.

Outside of the context of sleep restriction, exercise has well-known effects on improving mood and increasing alertness/wellness. This doesn’t seem to be the case when we’re sleep deprived, as suggested by this study.

Like the authors, my initial hypothesis was that the exercise group would be partially protected against sleep-restriction-induced cognitive/mood dysfunction; demonstrating higher scores compared to the SR group.

What could explain why exercise “didn’t work”? Perhaps the HIIT session, rather than giving participants a cognitive boost, actually diminished their mental energy. It can be hard to perform exercise when we’ve not gotten enough sleep — maybe the return on the energy investment just wasn’t great enough.

Nonetheless, doing exercise (such as HIIT) during periods of forced/voluntary sleep restriction seems to be practical (the participants successfully completed all sessions) and yields other benefits unrelated to cognitive function.

As discussed earlier, findings from this same study (separate publication) indicate the SR + EX group had better glucose tolerance and protein synthesis throughout the study as a result of performing exercise.

Thus, although participants in the SR + EX group didn’t seem to “feel” better during the period of sleep restriction, their physiology was benefitting.

Of course, the first-line strategy for preventing cognitive/mood dysfunction is to get enough sleep, but that’s not always possible. In that case, exercise can keep you working closer to baseline.

I’m experiencing this firsthand — my average nightly sleep went from ~8 hours to ~6 hours after the birth of our son 3 months ago. I’ve continued to train (even increasing my volume a bit) and I am without a doubt better off than if I’d stopped my regular workout routine.

The hardest thing about exercising whilst sleep deprived is garnering the motivation to do so. If we can get over the inertia, there’s good evidence to suggest that a little exercise can offset the ravages of a few nights of poor sleep.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

Loved this post. Thanks Brady!

“Skims article to end in groggy state” “Ah good, time for some push-ups!”