Introducing the Sleep and Cardiovascular Disease Series

Epidemiological evidence linking poor sleep to worse heart health.

Frequent readers of my blog and newsletter will be aware of my interest in sleep, cardiovascular health, and their interaction.

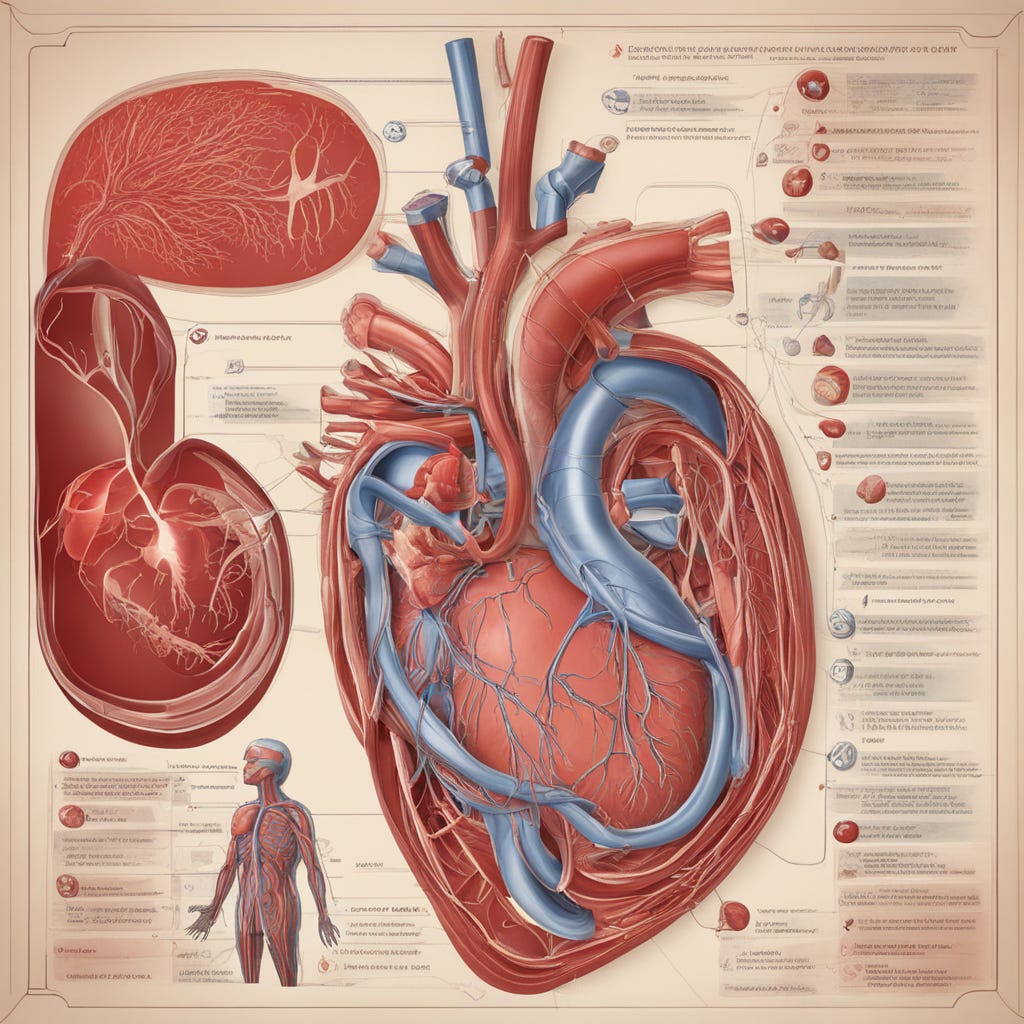

My interest in this topic emerged during my time in graduate school, when I was involved in a small study investigating the impact of sleep deprivation on endothelial (blood vessel) function. This led to the publication of a systematic review on the topic, which you can check out here.

As such, I’ve spent the better part of the last 7 years learning all about cardiovascular health and how it’s impacted by our lifestyles: of which sleep is a major pillar.

In the coming weeks, I’ll be publishing a series of posts on sleep and cardiovascular health.

Here’s what to look forward to:

Part I: Sleep and Cardiovascular Disease: The Epidemiological Evidence and Sex Differences in Risk

Part II: Circadian Rhythms, Sleep, and Cardiovascular Disease

Part III: Sleep Deprivation and Blood Vessel Health

Part IV: Mechanisms Underlying the Effects of Sleep Loss on Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Part V: How Exercise Protects against the Effects of Sleep Loss

Sleep and CVD: The Epidemiological Evidence

Every organism on earth needs to sleep.1

Despite our knowledge that sleep is vital for human health and well being, we often neglect it. It’s easy to do in our modern environments: social, technological, and other lifestyle factors allow us to live, work, and play around the clock if we so choose. In favor of nearly unlimited alternatives, sleep is often neglected.

The statistics reflect this negligence. More than one-third of U.S. adults report sleeping less than 7 hours each night and another 30% sleep fewer than 6 hours.23

In fact, as many as 48% of adults fail to get the proper amount of sleep each night,4 which is 7-9 hours according to the latest recommendations from the National Sleep foundation.5 Around 20% of college students report staying up all night at least once per month6 (a statistic that’s probably not surprising to anyone who attended).

These data imply that both acute and chronic sleep deprivation are public health issues, though the latter is certainly the primary cause for concern. as it’s associated with numerous long-term health risks.

Reducing our sleep has not come without consequence. Insufficient sleep has been linked to a greater risk for several health conditions including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cognitive decline, among others.78 A single night of insufficient sleep causes blood sugar control to resemble that of someone with diabetes; one can only imagine what chronic insufficient sleep can lead to.

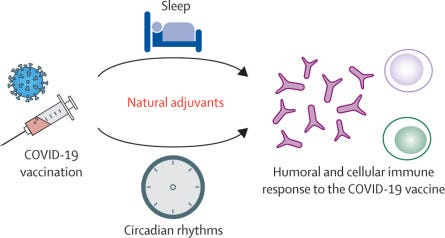

Sleep may have also played an underemphasized role in the COVID-19 pandemic.

In a commentary published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, sleep experts Christian Benedict and Jonathan Cedernaes argue (with data) that a poor night of sleep before or after a vaccination could possibly reduce its efficacy. It’s well known that sleep helps regulate the immune system, aiding our body’s fight against invading pathogens.

When it comes to cardiovascular health, the data are no less profound.

Sleep has a crucial role in regulating the myriad functions our cardiovascular and autonomic nervous system. At night, our heart and blood vessels receive a “rest and reset", without which we begin to experience problems. Sleep isn’t just a period of rest though; it’s a time when our body actively undergoes repair.

A lack of sleep thus causes the dysregulation of several cardiovascular functions which, over time, compound to increase CVD risk.

Let’s take a look at some of the epidemiological data on sleep and CVD.