The Risks and Benefits of 'Too Much' Exercise

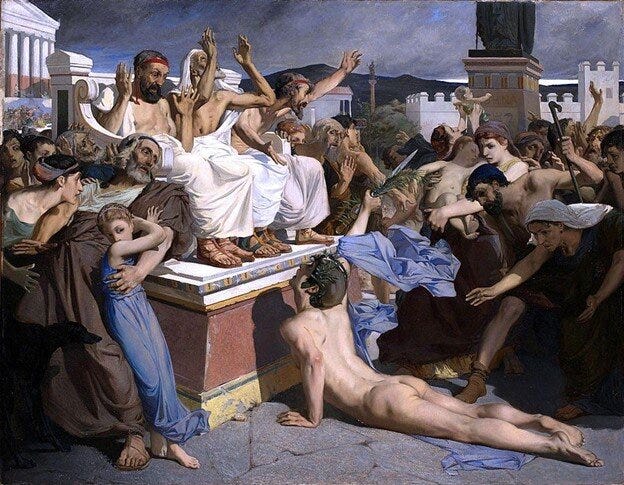

The marathon proved fatal for Pheidippides, but running one might help you live longer.

Athens, Greece

September 12, 490 BCE

This is the site of the first known fatality related to endurance running. Upon arrival to Athens, running the now-revered distance of 26 miles (and change) to deliver a message of a military victory against the Persians, Pheidippides, our Greek hero, collapsed, most likely due to sheer exhaustion on behalf of his previous effort.

“Joy to you, we’ve won” he said, and there and then he died, breathing his last breath with the words “Joy to you.”

While an awe-inspiring anecdote, our knowledge of human limits, physiology, and the sheer number of participants in endurance sports is enough evidence to conclude that running a marathon won’t kill you.

Pheidippides’ story is provocative. Perhaps it tells a tale of what the human spirit can accomplish if truly pushed to the limits.

Far from a warning for everyone to avoid running, this tale has created a lust around the modern 26.2 mile distance — Pheidippides lives on as hordes of runners try to recreate his heroic effort each weekend around the world.

Indeed, marathon running, and endurance sport participation in general, has hit a revival. This is supported by the over 1 million marathon participants worldwide in 2019. These numbers indicate rising participation — an increase in people involved in chronic endurance exercise training for the sake of competition and health.

Is there a downside to this participation?

Opponents of endurance running like to cite the infrequent cases of modern-day Pheidippides as reasons as to why endurance running is dangerous. Some guy dies during a marathon and suddenly running is bad for you.

A comprehensive list of marathon-related deaths on Wikipedia contains 47 cases of “death by marathon” in the U.S. and elsewhere, up until 2016.

A list of the causes of death reveals an underlying pattern. Many, but not all, are cardiac-related issues (i.e., heart attack, arrhythmia, underlying congenital heart abnormality). We know exercise, and especially a marathon, stresses the heart. A list like this indicates that endurance running may in fact be detrimental to the cardiovascular system.

However, these 47 deaths were over the span of 35 years, during which some 4 million plus people finished a marathon. What this amounts to is around 0.9–1.6 deaths per 100,000 marathon finishers.

While it’s undeniable that lack of preparation, underlying cardiac issue, or freak accident may make one susceptible to irreversible injury or death while running, we can’t ignore the facts — very few people on a population-wide level suffer from life-threatening incidents after endurance exercise.

Nonetheless, too much of anything can be harmful, and there are mechanisms to explain why endurance running may be harmful to the heart when done to extremes.

An argument against life-long high-intensity endurance training is that it may actually lead to unfavorable adaptations such as the “athlete’s heart.”

Isn’t exercise good for us?

We know that this answer is a resounding yes. But is moderation key?

Does exercise pose an acute cardiovascular risk?

A large amount of endurance-exercise-related deaths occurred due to a cardiac incident during or following activity.

Vigorous exercise is known to increase the risk of sudden cardiac death. However, this increased risk manifests mostly among individuals with an underlying cardiac disease.

For instance, younger (less than 30 or 40 years of age) individuals who suffer from sudden cardiac death during exercise are usually found to have an inherited or congenital cardiac condition, also known collectively as cardiomyopathies. Indeed, 44% of deaths among athletes in the U.S. were shown to be due to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy — an inherited condition of an enlarged heart.

In older adults, reasons for death often include further cardiovascular issues such as coronary artery disease, increasing the susceptibility to risk of injury or death during high exertion activity. One study examining the risk of sudden cardiac death in male physicians (a healthy cohort) concluded that, while the risk of death was 16.9% higher during vigorous vs. lower intensity exercise, the absolute risk was still extremely low — 1 death per 1.42 million hours of vigorous exercise.

But the risk of suffering from a cardiac incident during exercise goes down as you get fitter.

When comparing the risk of death during exercise to one’s baseline physical activity levels, risk drops with increasing levels of activity. Additionally, among a study of 84,888 women, those who exercise 2 or more hours per week had a decreased risk of suffering an exercise-related cardiac event.

Why does exercise increase the risk of a cardiac event?

Lower cardiac function (due to cardiac fatigue, which only occurs after high-intensity or long-duration exercise) may be one way in which the risk for injury rises during or after exercise.

As we activate our sympathetic nervous system and release epinephrine and norepinephrine during exercise, heart rate and the force of the heart contraction (known as contractility) both increase. Over a long-term exercise bout, our heart may be unable to handle the increased physical demands and may reduce its function. Not to worry — unless your exercise routinely lasts more than 3 hours, many of these detrimental processes are unlikely to take place.

Long term exercise training and the heart: are the adaptations detrimental or beneficial?

Most of the argument over whether long-term endurance training is harmful centers around a concept referred to as the “athlete’s heart.”

The athletes heart refers to adaptations of the heart including mild to moderate enlargement of the ventricles and the heart walls, enhanced left ventricle filling, enhanced heart mechanics (twisting and untwisting during contraction), and an enlargement of the atria.

In contrast to the negative left ventricular hypertrophy that is characteristic of many cardiovascular disease conditions (characterized by a thicker left ventricle wall, but a ventricle that “shrinks” causing the heart to under-perform) — eccentric hypertrophy that occurs with training has been referred to as a positive adaptation, allowing more blood to be filled and then ejected from the ventricle. This allows for more blood delivery during exercise.

Trained athletes present with increased left ventricle size compared to untrained individuals. A study noted that out of 13,000 Italian athletes who underwent an evaluation, 45% had a left ventricle diameter greater than the upper limit of normal.

A few other key findings in athletes — improved diastolic (filling) function and more compliant arteries — provide evidence that heart function may be improved with long term training, despite some structural changes occuring.

But is the athlete’s heart benign? What type of damage might be caused by too much exercise?

In an editorial for the British Medical Journal, cardiologists James O’Keefe and Carl Lavie cite physiological changes including overstretching and micro tears in the heart muscle, fibrosis (stiffening) of the heart wall, increased calcification, remodeling of the ventricles, and stiffening of the arteries as among the “pathophysiological” changes caused by exercise.

Indeed, excessive endurance exercise might promote changes that resemble cardiac aging. Some studies show that high-level endurance runners present with more fibrosis and plaque than age-matched controls (non-runners), data which I’ve covered in detail previously.

The authors of the editorial go so far as to conclude that “running too fast, too far, and for too many years may speed one’s progress towards the finish line of life.”

Fear-inducing for heavy exercisers? Perhaps. But for those who meet the criteria of “extremist”, there’s some promising data on the link between physical activity and cardiovascular death and disease.