Physiology Friday #180: Dysregulated Sleep Worsens Blood Sugar Control

When sleep suffers, so does metabolic health.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

This newsletter is brought to you by Examine.com, PodScholars, and my new eBook, “VO2 Max Essentials”, details for which can be found at the end of this newsletter.

We hear enough about how sleep is one of the cornerstones of health, and at this point, anyone unaware of the importance of sleep is living under a rock. If you want to perform at your best — physically and cognitively — a healthy sleep habit is a must. Recent research is also showing that “good sleep” is much more complex than just getting 6—9 hours each night. Light and noise exposure during sleep, temperature, sleep timing, and sleep regularity are crucial variables to consider.

Hundreds of studies have been published in the last few years alone on how sleep (or a lack thereof) impacts physical performance, attention, emotional regulation, appetite, and metabolic health.

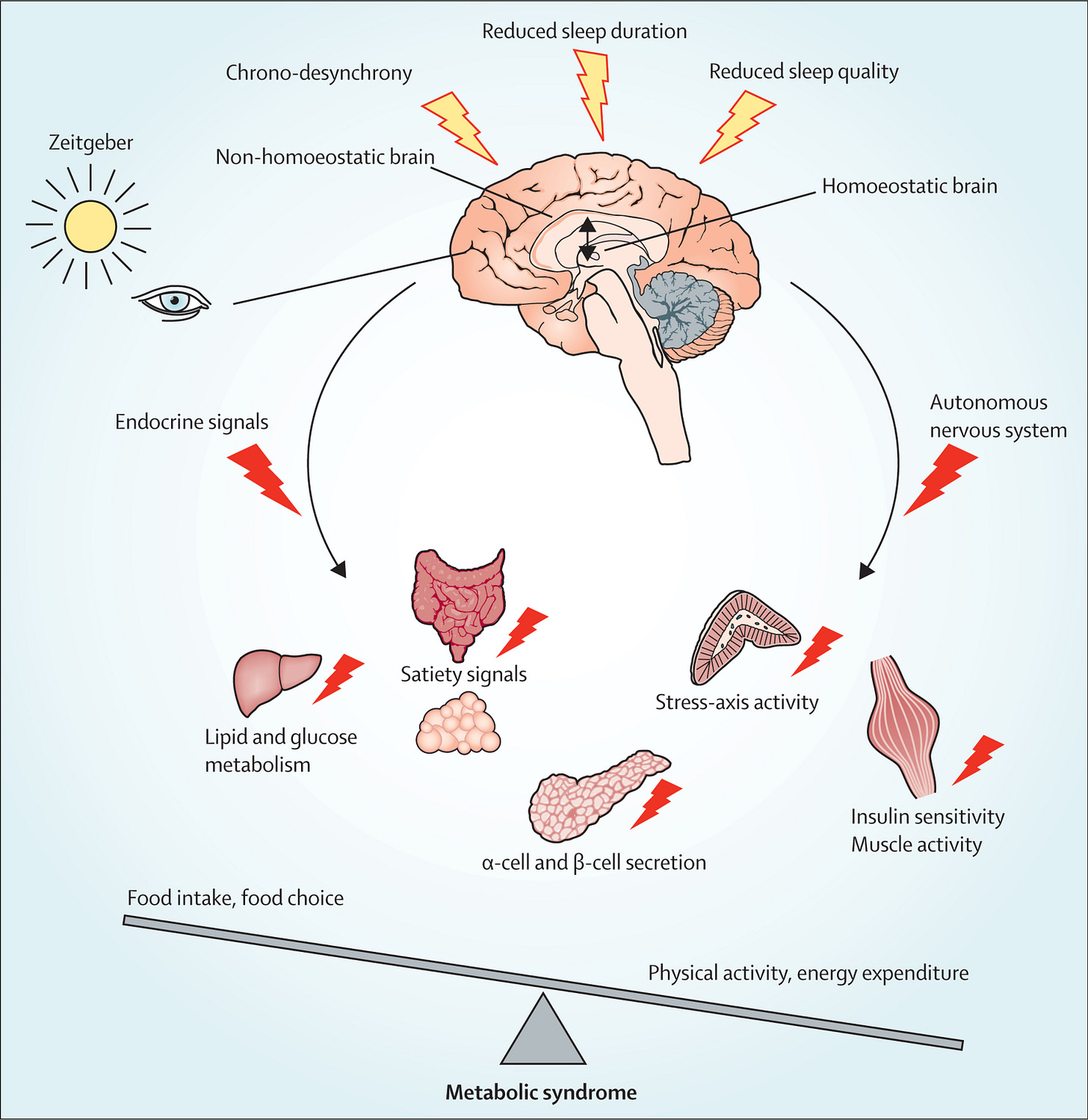

In particular, poor sleep has consistently been linked to impaired metabolic regulation and a variety of metabolic conditions including obesity and type II diabetes — the latter characterized by reduced insulin sensitivity which leads to elevated blood glucose and high postprandial (postmeal) blood glucose levels.

Studying sleep in the laboratory is one thing, but using field-based methods of analyzing sleep (such as activity monitoring) allows researchers to monitor how people sleep outside of the lab (in their real life), which is more applicable and is, for some people, more meaningful data than that gathered under controlled conditions that limit a study’s generalizability.

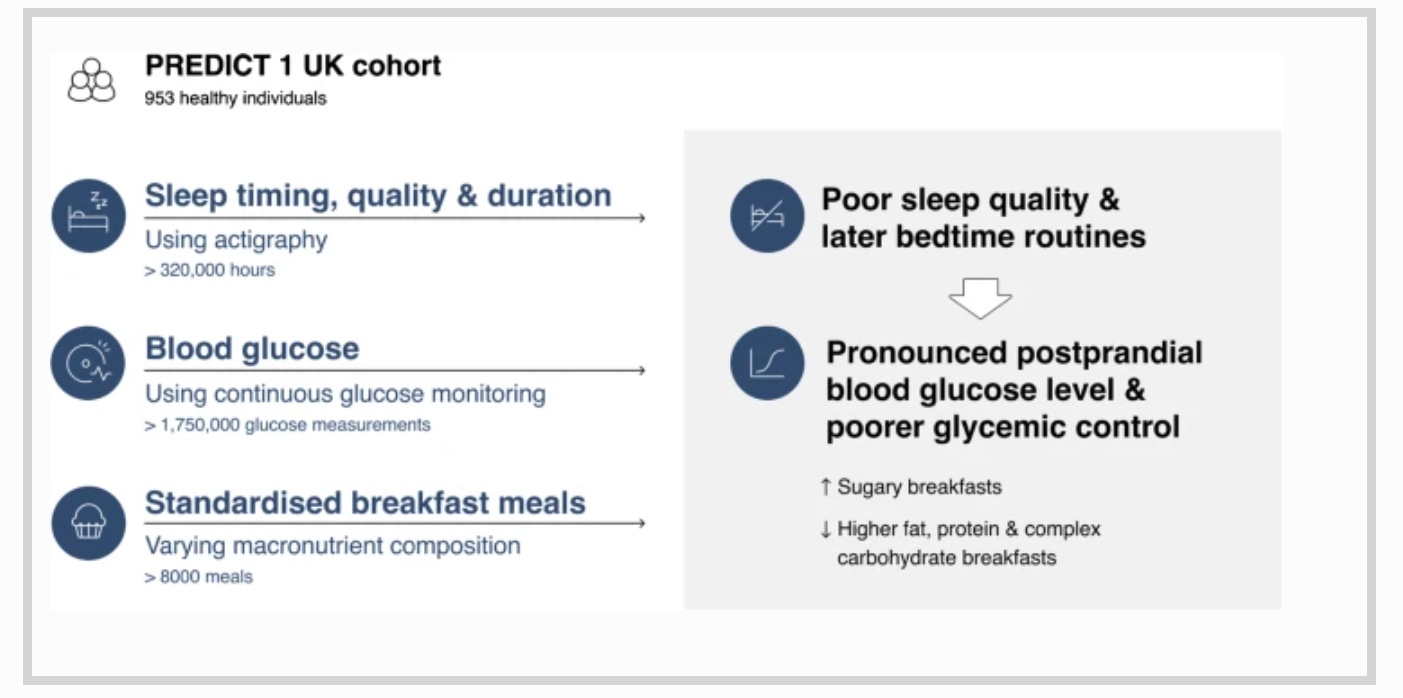

Research published in the journal Diabetologia1 took a real-world approach to measuring sleep metrics and blood glucose responses to meals in order to disentangle the complex relationship between sleep and metabolism. How do sleep patterns influence our “tolerance” to various meals?

The study included a total of 691 participants from the UK and the USA with an average age of 45.

For 14 days, participants had their sleep and sleep characteristics monitored using a wrist-worn accelerometer, which was able to gather information on their total sleep duration, sleep efficiency (an indicator of sleep quality), and sleep midpoint (the middle of their sleep period).

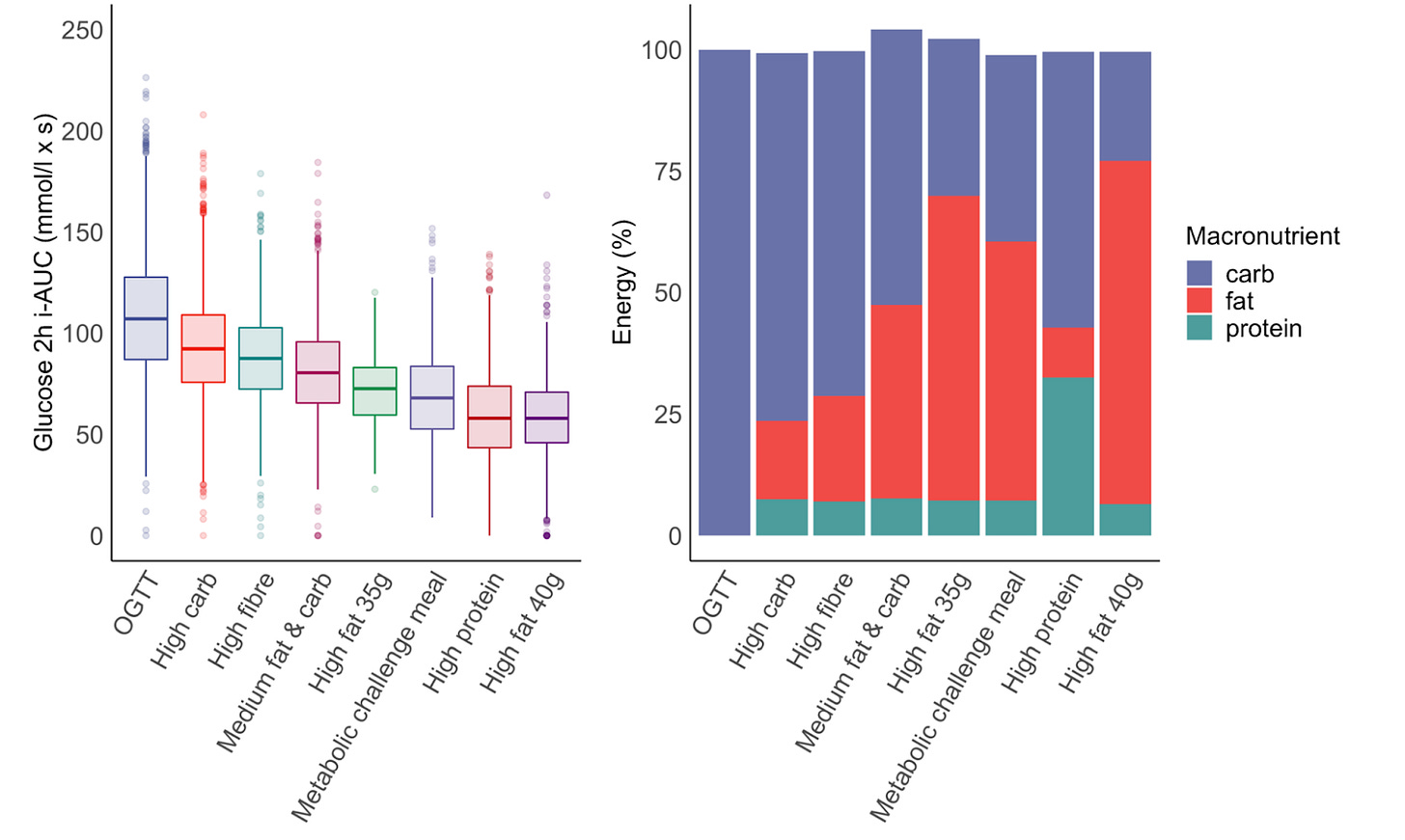

During this time, participants also consumed 8 different meals or “meal challenges”: an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), a high-carb meal, a high-fiber meal, a medium-fat and medium-carb meal, a high-fat meal (35 grams of fat), a metabolic meal challenge, a high-protein meal, and a high fat meal (40 grams of fat). The macronutrient composition of these meals can be seen in the graph below along with the average glucose response to these meals for all of the participants.

Participants were also fitted with a continuous blood glucose monitor (CGM), which took a blood glucose reading every 15 minutes throughout the study and, most importantly, after each breakfast meal listed above. This data allowed for the calculation of the study’s primary outcome — the 2-hour postprandial glucose response (expressed as incremental area-under-the-curve) to each meal and, subsequently, how this glucose response related to the participant’s sleep characteristics.

Results

Total sleep time

There was no association between total sleep time and 2-hour glucose AUC, however, a significant interaction was found for sleep time and meal type: shorter sleep was association with a greater (worse) glucose response after high-carbohydrate and high-fat meals.

Getting more sleep than normal (for any particular participant) was associated with a lower (better) glycemic response to the high-carb and high-fat meals. In other words, sleep extension improved glucose tolerance.

Sleep efficiency

Greater sleep efficiency was associated with lower 2-hour postprandial blood glucose, and within each individual, improving sleep efficiency improved glycemic responses to any given meal.

Sleep midpoint

Regarding sleep midpoint, a later sleep midpoint (due to a later bedtime) was associated with worse glycemic control at breakfast. Delaying bedtime led to a higher glucose response.

It is interesting to see that out of all variables measured in this study, sleep duration (or total sleep period) was not associated with 2-hour glucose.

However, as the authors note, a lack of association in this study may be due to the fact that most participants actually had a sleep duration that fell within the recommended range; even the lowest quartile achieved around 6.87 hours of sleep per night.

The novel findings here are that sleep quality (assessed as sleep efficiency and sleep midpoint) were related to postprandial glycemic control — suggesting that it is not just how much one sleeps but, perhaps more importantly, how well, at what time, and the consistency to which one adheres to their sleep schedule.

The latter point about consistency should be underscored. This study found that when someone goes to bed later than usual (thus giving them a later sleep midpoint), their glycemic control at breakfast the next day is worse.

Going to bed (and waking up) at the same time each day is emerging as one of the most important factors for sleep as it relates to metabolic health.

The application of these findings are pretty straightforward. Whether you’re a breakfast eater or not, getting the proper amount of sleep and improving the quality and consistency of your sleep schedule will lead to better glucose control surrounding meals — regardless of what those meals might be.

Poor glucose control is a risk factor for diabetes but can also exert negative effects on aspects of aging, cardiovascular health, and cognition.

Whether you choose to eat a high-carb diet, low-carb diet, or any variation in between, taking control of your sleep hygiene will help you live the healthiest and best life possible. Our body seems to operate best when we live in a rhythm, at least most of the time.

Thanks for reading, see you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

PodScholars: PodScholars is the first podcasting platform and database specifically geared towards published research, where scholars, researchers, and other experts can broadcast published science as audio or video casts.