Physiology Friday #218: The Longevity Advantage of Elite Middle Distance Runners

Is a fast mile the secret to living longer?

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter including Examine.com and my book “VO2 Max Essentials” can be found at the end of the post!

You won’t find a more potent longevity drug than exercise.

I think that we have enough evidence to conclude that other than maintaining a healthy weight, being physically active is the single best thing you can do to maximally reduce your risk of disease and minimize your chances of dying early.

“To exercise, or not to exercise” is not the question. Rather, intense debate surrounds what the optimal dose of exercise is for longevity. It’s clear that too little is detrimental. But could the same apply to too much?

“Extreme exercise” — either in duration, intensity, or both — certainly places a stress on the body and in particular, the heart. The idea that years and years of accumulated stress may predispose lifelong athletes to heart disease and other ailments has thus been proposed.

Most of the evidence on the harms of extreme exercise is related to a biomarker of cardiovascular disease known as coronary artery calcification or CAC.

Numerous reports in the last decade have found that lifetime endurance athletes have higher levels of coronary artery calcification and plaque compared to age-matched non-athletes.

What’s lacking, however, is good data on long-term survival and lifespan among “extreme exercisers.” Biomarkers of cardiovascular disease are one thing. Hard endpoints like death mean more.

Who better defines the idea of “extreme exercisers” than elite-level runners? If we want to really understand if lifelong endurance training shortens lifespan, we’d best study the crème de la crème. That’s what a new observational study published in the British Medical Journal did.1

For the study, the researchers compiled a list of the first 200 men to break the 4-minute mile barrier (the first was Sir Roger Bannister, who broke the 4-minute mile barrier just around 70 years ago and also lived to the ripe old age of 88).

The men were born between 1928 and 1955 and had an average age of 23 at the time of their achievement. This cohort comprised men from Europe, North America, Oceania, and Africa.

Using publicly available birth and death records, the average age at death (or the average current age for those still living) was calculated and compared to the average life expectancy of the general population matched for age and sex. The difference in life expectancy of the 4-minute milers and the general population was then calculated.

Of the entire cohort, 60 had died and 140 were still alive at the time of the study. Those who died did so at an average age of 73.6 and those who were still alive were, on average, 77.6 years old.

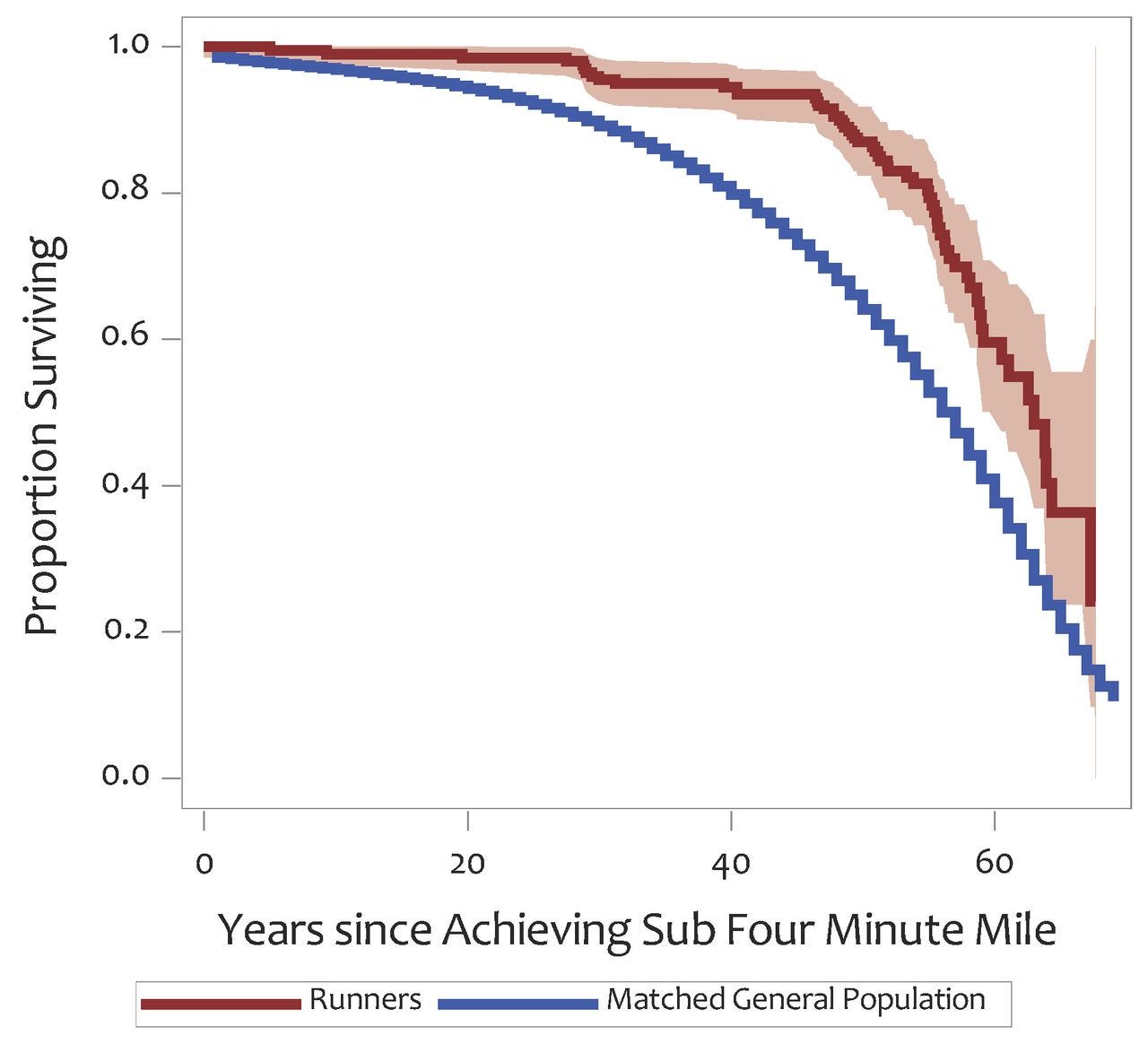

Compared to the general population, the 4-minute milers had a 4.7-year increase in their life expectancy.

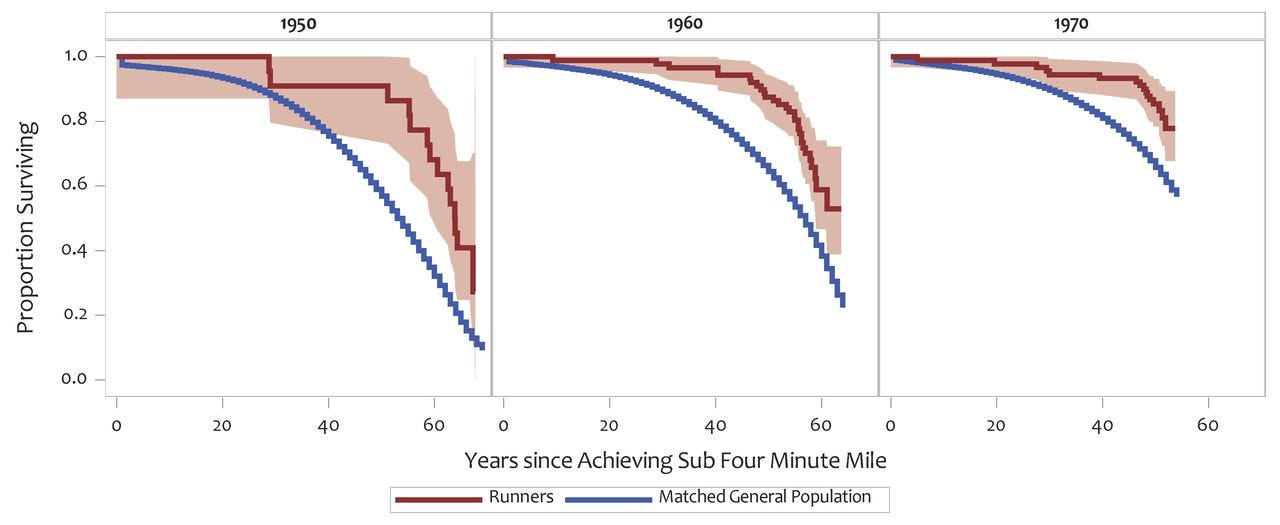

Interestingly, runners who were born in the 1950s lived an average of 9.2 years longer than their predicted life expectancy, which may reflect improvements in healthcare in subsequent decades that led to increases in the life expectancy of the general population. This is supported by the fact that runners born in the 1960s lived an average of 5.5 years longer than their predicted life expectancy and those born in the 1970s only lived an average of 2.9 years beyond their predicted life expectancy.

Does being elite among the elite improve life expectancy further?

To investigate this question, the researchers compared life expectancy among runners who competed in the Olympics vs. those who didn’t. They found no longevity benefit to being an Olympian: Olympians and non-Olympians lived 4.1 years and 5.7 years beyond their predicted life expectancy, respectively.

There are a number of limitations with this study that should be noted. For one, it’s observational and therefore we can’t imply causation. Second, causes of death weren’t available for most of the study cohort, and therefore we don’t know if the athletes had a higher prevalence of certain diseases compared to the general population. Third, data on other metrics like lifetime exercise volume, cardiorespiratory fitness, and biomarkers weren’t assessed.

This prevents us from concluding that running a 4-minute mile causes you to live longer.

But the results of this study do call into question some of the recent concerns that high-level endurance exercise may be detrimental to longevity.

While it’s true that coronary plaque levels may be higher among athletes, when we look at lifespan data, the story changes.

Endurance exercise appears to protect against death from cardiovascular diseases and all causes, and several studies (including the present one) have observed greater longevity in elite endurance athletes compared to the general population. For example, U.S. Olympians have a 13 to 20% greater survival probability than the general U.S. population.

Participating in high-level physical activity for several years to decades doesn’t appear to shorten your life. In fact, it adds nearly have a decade to it if we can believe the results of this study.

What could explain the greater longevity in exceptional athletes?

There’s obviously the possibility that genetic selection is at work — are elite athletes blessed with good genes that allow them to perform at a high level and live long? Perhaps.

But it’s also quite likely that physical fitness is lifespan-enhancing. Readers of my Substack will be well aware that the higher your cardiorespiratory fitness (i.e., your VO2 max), the longer your life.

It likely takes an incredibly high VO2 max to be capable of running a mile in under 4 minutes — or at least the training that’s required to get to that level will produce a high VO2 max.

There’s no VO2 max data available for the group of 200 runners from this study, but other studies have characterized fitness levels of elite-level mile/1500 meter runners. One study of middle-distance runners observed an average VO2 max of 68.9, and another study of Spanish 1500 meter runners observed an average VO2 max of 73.9.

I think it’s reasonable to assume that the 200 men comprising the elite miler cohort of the present study probably had a VO2 max in the range of 65 to 75 or more. These high levels of cardiorespiratory fitness no doubt contributed to the longevity advantage of elite runners.

Don’t despair if you don’t have an “elite” VO2 max or if you can’t break 4 minutes in the mile (join the club). Neither is necessary nor sufficient to live a long healthy life. Exceptional longevity has been achieved by people who probably haven’t run a mile in their life (that’s the genes talking).

I’ll reiterate that there are limitations to observational studies of this nature, but it’s the best evidence we have to rely on until we get a multi-decade controlled trial of “extreme exercise” versus a control group. That’s unlikely to happen anytime soon.

I think there are two major takeaways from this study.

One: the fears of “extreme exercise” aren’t substantiated. You can train at a high level and live a long life.

Two: engaging in dedicated exercise training that works to improve on a personal best, elevate your VO2 max, or both, seems to be a valid longevity strategy.

Have a purpose to your training and strive toward a fitness goal, just as all of those men did when they cracked the 4-minute mile barrier.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

I guess the biggest confounder here is selection. People with "suboptimal working" metabolism, chronic genetic clinical or subclinical conditions are probably less likely to be able to run <4 min mile. Same for people starting to smoke very early a lot, drink a lot of alcohol, get obease, ... . With that in mind, 4.7 years are actually not that much.