Physiology Friday #273: Is Time-Restricted Eating Sabotaging Your Workout Results?

A new study encourages us to rethink muscle building in a world of intermittent fasting.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Are you injured, training for your first competition, or simply looking for some personalized training advice?

If so, I’d highly recommend checking out the Elite Edge ReBUILD program—started by my good friend Max Stoneking. Elite Edge is the premier destination for athletes, looking to rebuild back from an injury or chase performance goals in running, triathlon or the like.

With a Coach skilled on rehabilitation, training and performance, Athletes will find themselves building a partnership with Max that Goes far beyond the races. He’s been influential in my own rehabilitation process and offers a variety of services based on your individual needs. Visit eliteedgecoached.com to learn more.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter including Ketone-IQ, Examine.com, and my book “VO2 Max Essentials” can be found at the end of the post. You can find more products I’m affiliated with on my website.

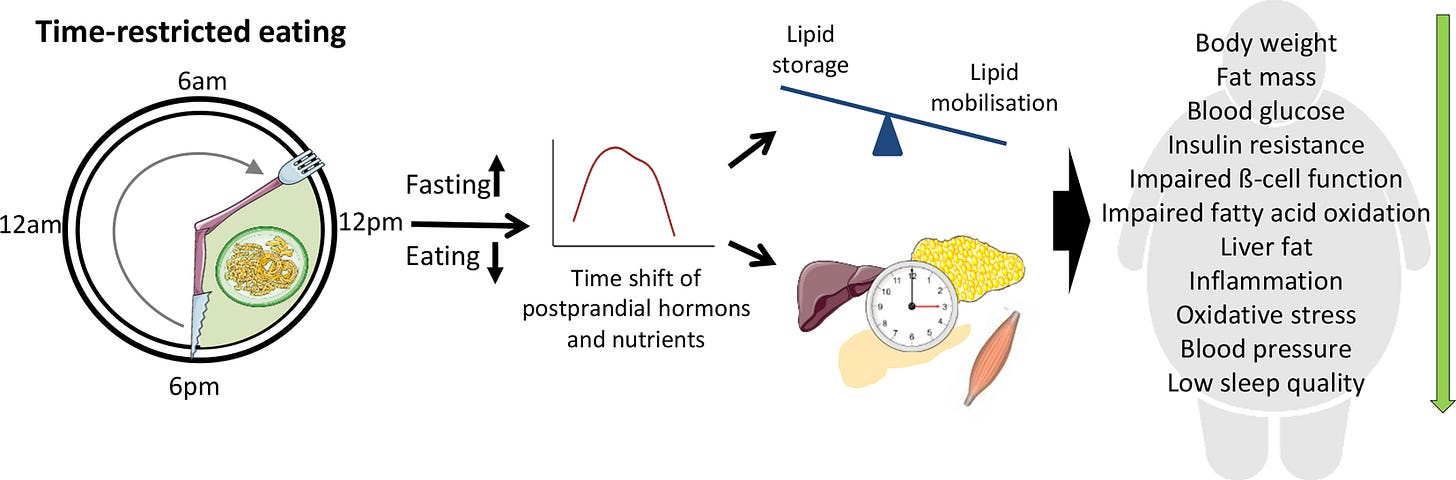

Time-restricted eating (or TRE for short) is a buzzword in the health space but, surprisingly, there’s a lot of good evidence to support this way of eating. By aligning meals with our body’s circadian clock, TRE works in favor of our biological rhythms to support health and longevity.

However, when it comes to performance nutrition—jumping higher, running faster, lifting heavier, etc.—the evidence isn’t so clear cut.

At its simplest, TRE confines all caloric intake to a narrow daily window—often 8 hours—followed by a prolonged overnight fast. There’s not anything special about it: everybody sleeps, ergo everybody fasts. But most Americans (and most people around the world) often consume food within a 16-18 hour window, leaving only a meager 6-8 hours per day when they’re in a “fasted” state.

For metabolic health, TRE seems promising. It can help improve insulin sensitivity, manage blood pressure, and might have a minor edge when it comes to weight loss compared to conventional calorie restriction. Some people (myself included) just find the pattern to be an easy and enjoyable way to eat.

But not everyone is a fan of TRE, for decent reasons. Skipping meals or fasting too long before and after workouts can have negative effects on training adaptations, especially for athletes in energy-demanding sports where fueling is paramount to performance.

Nonetheless, advocates point to studies suggesting that front-loading fasting hours—a strategy known as early TRE—can sharpen metabolic flexibility, elevate growth-hormone release, and make it easier to eat in line with circadian rhythms. This, presumably, could benefit body composition, athletic performance, and even muscle gain.

Critics counter that extended periods without fuel could blunt glycogen resynthesis, impair high-volume training, and erode the very muscle athletes work so hard to build.

Those opposing narratives share one blind spot: Most existing data come from weight-loss interventions, not muscle-gain phases. In caloric-deficit studies, TRE usually protects lean mass while helping subjects drop fat—an attractive outcome for athletes competing in weight-class sports or people with overweight or obesity.

But building muscle and strength (and even improving speed and endurance) is metabolically different. Building new contractile tissue (a fancy word for muscle) demands a sustained surplus of energy and amino acids, and conventional wisdom insists that evenly spaced protein feedings maximize the anabolic machinery of muscle. In other words, a feeding pattern uncharacteristic of TRE.

So here’s the question: Does compressing meals into an eight-hour window undermine that process—or might it let athletes add size while simultaneously improving body composition?

A new study co-authored by Dr. Andy Galpin tackles that question head-on, pitting a 16:8 TRE protocol against a traditional eating schedule during eight weeks of intense, hyper-caloric resistance training.1

The study involved 17 healthy, resistance-trained individuals (10 men, 7 women) divided into two distinct dietary regimens over eight weeks. Both groups adhered strictly to a hypercaloric diet—consuming approximately 10% more calories than their baseline energy requirements—with a high protein intake set at 2.2 grams per kilogram of body weight daily (or 1 gram per pound). However, the timing of their meals differed markedly:

The TRE group ate all their daily calories within a strict eight-hour window, starting at least one hour post-exercise, typically finishing their meals later in the day. That means they exercised fasted and remained fasted for at least 60 minutes after their workout. A crucial detail.

The control (FED) group consumed the same caloric surplus spread across approximately 13 hours, including eating a meal before their morning training session.

All participants completed identical, carefully supervised resistance training routines four times per week, employing progressive resistance exercise methods to maximize muscle strength and size.

Despite significant differences in meal timing, both dietary strategies supported substantial gains in fat-free mass (including muscle). TRE participants gained an average of 2.67 kilograms of lean mass, while FED participants increased their muscle mass by approximately 1.82 kilograms—numerically different but statistically speaking, similar gains.

Some clear distinctions emerged when examining strength gains and training volume. Both groups improved their lower body strength, but TRE participants saw significantly less improvement in maximal squat strength—around 4 kilograms less than FED. Total reps (training volume) across the training period were notably lower in the TRE group (6,960 reps) compared to the FED group (7,334 reps), indicating reduced overall training capacity or increased fatigue in the fasting group.

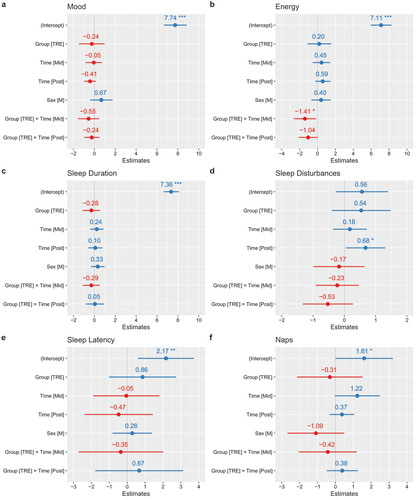

The TRE participants consistently reported lower subjective energy levels, particularly at the study’s midpoint (week 4), which may partly explain their decreased training volume and slightly impaired strength gains.

Interestingly, the TRE group exhibited significantly less fat gain (0.26 kilograms) compared to their FED counterparts, who gained around 1.67 kilograms of fat—that’s a noteworthy difference given that both groups consumed a similar total caloric surplus. This outcome suggests that TRE might offer superior nutrient partitioning, potentially leveraging fasting-induced hormonal shifts to limit fat storage during periods of caloric excess.

Importantly, several outcomes were NOT different between the groups, a point that should be underscored given the somewhat varied diet patterns.

Strength and muscular performance (bench press 1RM, leg extension 1RM)

Muscular endurance (bench press, leg press)

Total body mass (overall weight gain) and fat-free mass (lean mass)

Nutrition and dietary adherence including caloric intake, protein intake, fat intake, and “difficulty” adhering to each diet

Exercise and training outcomes (total training days completed, average load during training sessions, total tonnage (load x volume across the 8-week study)

Subjective ratings of mood, sleep quality and duration, sleep disturbances, and naps

Does this study prove once and for all that when you eat doesn’t really matter that much if your goal is to gain muscle, build strength, or improve your body composition? Not quite.

While meal timing may not strongly affect short-term exercise performance (as shown in this study), the cumulative impact of fasting on recovery, hormonal responses, and psychological factors like perceived energy availability could become significant over several weeks, especially under intense training conditions.

After all, there were some minor but noteworthy differences in training quality observed here, and that could have to do with the pre- and post-workout nutrition timing.

Carbohydrate timing, particularly immediately post-exercise, is known to enhance recovery, maintain glycogen stores, and optimize performance in subsequent training sessions. The delayed intake in the TRE group could have hindered optimal recovery between sessions, negatively affecting training quality especially as the training progressed. If this study had gone beyond 8 weeks, I speculate the differences between the groups would have become even more drastic.

Nevertheless, this study provides evidence that 16:8 intermittent fasting can be effectively integrated into muscle-building diets, with some notable advantages for body composition. However, athletes and serious trainers might approach TRE with cautious consideration of their specific performance and recovery demands. That might mean modifying TRE to include breakfast or at least an immediate post-workout meal to optimize recovery. Fasted exercise and TRE don’t have to be mutually exclusive.

Personally, I’m a fan of TRE even though I’m not religious about it. I stop eating around 8 at night and break my fast soon after my morning workout—often resulting in a 12–13 hour fast. I used to delay my first meal by a few hours before coming to the obvious conclusion that this wasn’t helping—and in fact, was probably hindering—my training and performance. Athletes have to fuel properly, but this doesn’t mean we can’t also practice a circadian-friendly eating pattern.

Consider the myth that “you can’t build muscle while fasting” busted. If you eat enough protein and calories, it’s definitely possible.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

FSTFUEL combines electrolytes with amino acids to help your body maintain hydration and optimal functioning during exercise or intermittent fasting, so you don't have to choose between fasting and fitness. If you want to try some, the guys at FSTFUEL have agreed to give my audience a 30% discount on their orders. Just use the coupon code BRADY30 at checkout.

I've recently started reading your newsletter and enjoy it. As a 50-something who has had an up-and-down relationship with running (and eating/weight loss) over the past 3+ decades, I've been consistently running for about 6 years now, completing 3 HMs and finally, a FM about a month ago. Today's newsletter is particularly interesting to me because in January of 2024, I began intermittent fasting. While the immediate reason was to curb my weight gain before it got out of control (again), I had been coasting for a few years at between 170-180 lbs, which at 5'9" seemed pretty reasonable for me. Until I started fasting.

Early on, I mainly stuck to a 5-7 hour eating window. I workout/run at lunch most days, so most of my workouts are fasted. I make sure to eat within 15-30 minutes of finishing, though, as I understand that is important to maximize gains/recovery. So I'm curious why the study held people from eating for a full hour (although maybe the difference isn't that important?). In any event, my body fat percentage (as measured by a smart scale I purchased, not sure how accurate it is) went from 26% to under 12%, and at my lowest weight, I got down to 142 lbs (I'm now around 150). I feel great. And, while I don't do a ton of weight training, my biceps/triceps are bigger than they have ever been., and the lack of fat across my entire body is noticeable.

Since I'm in more of a "maintenance mode" now, I have a 6-8 hour eating window, and on vacation or when my schedule is out of whack, I will eat outside the window. Also important - when I do long runs, I eat a breakfast similar to what I eat on race mornings, and I will fuel during the runs. I'm a big supporter of IF, but I also understand the importance of fueling for performance.

I see no obstacle for TRE even with eating before session: I can have breakfast at 7 am then consume post recovery drink after, lunch at 12 and dinner at 5 pm.