Physiology Friday #280: Is 7,000 Steps Per Day the New ‘Sweet Spot’ for Disease Prevention?

The evidence is clear—more walking is better (and the limit doesn’t exist).

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

If you’ve jumped on the creatine bandwagon (who hasn’t) but aren’t sure where to start, I suggest you try out Create—the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of gummies (and yeah…their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands), flavored creatine monohydrate single-serve packets, and a daily performance greens gummy (my personal favorite).

This week, they’re giving my audience 25% off of their entire order, but the sale ends today. So stock up!

Details about the other sponsors of this newsletter, including Ketone-IQ, Examine.com, and my book “VO2 Max Essentials,” can be found at the end of the post. You can find more products I’m affiliated with on my website.

Did you get your steps in today?

Odds are, you did, and you know exactly how many. It’s rare to find someone who doesn’t own a smartwatch or activity tracker that tallies their every step. Steps have become the health metric du jour, partly because step-count studies have surged in recent years, each proposing a different threshold for optimal health benefits.

Some studies highlight modest gains at lower counts, such as 4,000–5,000 steps per day, while others advocate for mid-range targets around 7,000–8,000 steps or the well-known 10,000-step goal for significant disease risk reduction.

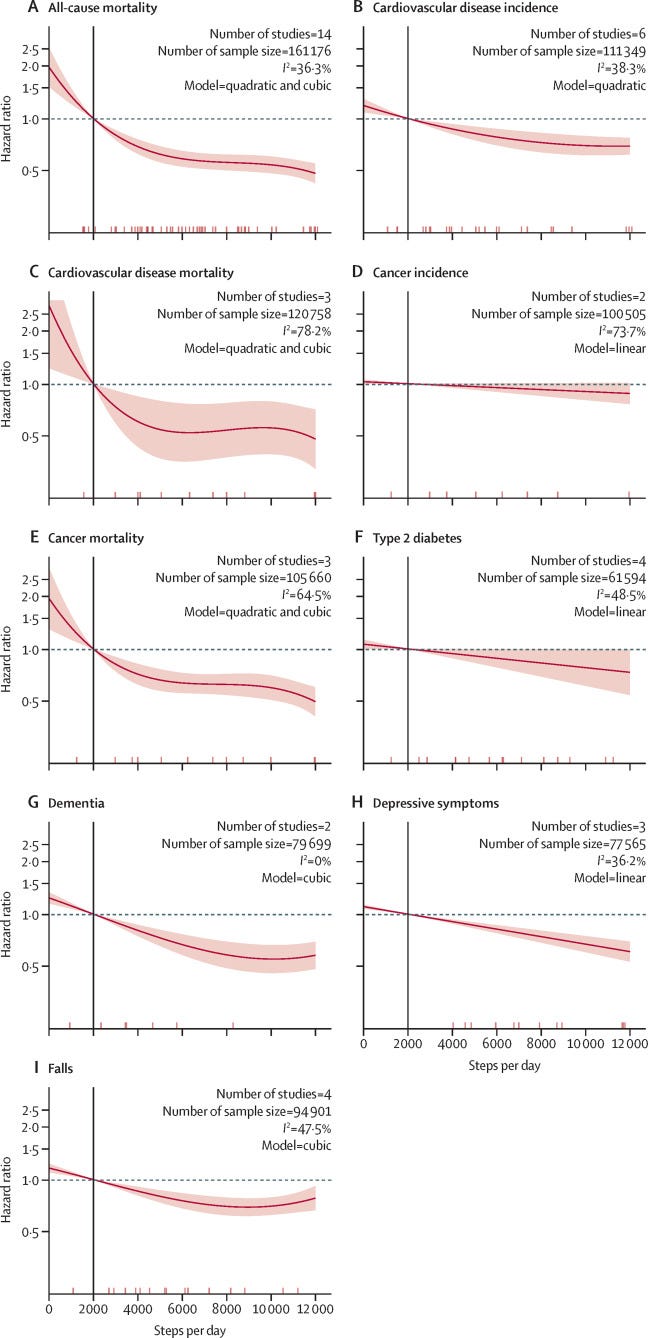

A common finding is a non-linear dose-response curve: very low step counts are associated with higher risks, and benefits increase with more steps, sometimes leveling off or slightly declining at very high counts (greater than 12,000). I attribute these declines at extreme step counts to limited sample sizes in most studies, as few participants consistently achieve such high daily totals. Confounding factors, such as overexertion in less healthy individuals or reverse causality, may also contribute. That said, we still don’t have a definitive answer to the optimal number of steps per day, as every study seems to propose a new “benchmark.”

Despite this variability, a clear trend emerges: higher step counts generally align with better health outcomes, often without a definitive point of diminishing returns. However, much of the step-count research has limitations.

Observational studies, including those using large-scale accelerometry data from cohorts like the UK Biobank or NHANES, face inherent challenges. Step counts, whether self-reported or device-tracked, are prone to measurement errors. These studies often fail to account for step intensity, accumulation patterns (e.g., sustained walks versus sporadic movement), or concurrent activities like structured exercise. Confounders such as socioeconomic status, diet, and genetics further complicate interpretations, and the predominance of data from high-income countries limits global applicability.

This leaves the question of causality unresolved: Does walking more prevent disease, or do healthier people simply walk more? Reverse causality is plausible, as those with emerging health issues may reduce activity. Long-term randomized controlled trials, while ideal for establishing causation, are logistically challenging, leaving us with robust but associative evidence.

The latest step-count meta-analysis,1 spanning cohorts from 2014 to early 2025, provides a robust update to the evidence base. It demonstrates that health benefits begin at relatively low thresholds. Compared to a baseline of 2,000 steps per day, achieving approximately 4,000 steps yields initial reductions in risk, including a 15% lower risk of all-cause mortality, a 6% reduction in cancer incidence (though borderline significant), and a 14% decrease in type 2 diabetes incidence.

At 7,000 steps per day, the benefits become more pronounced, with risk reductions ranging from 6–47% compared to the 2,000-step baseline. Specifically, this level correlates with a 47% reduction in all-cause mortality, a 25% lower cardiovascular disease (CVD) incidence, a 37% decrease in cancer mortality, a 14% reduction in type 2 diabetes, a 38% lower dementia risk, a 22% reduction in depressive symptoms, and a 28% decrease in falls. For outcomes like all-cause mortality, CVD incidence, dementia, and falls, the dose-response curve is non-linear, with the steepest benefits occurring around 5,000–7,000 steps. In contrast, CVD mortality, cancer mortality, type 2 diabetes, and depressive symptoms show a more linear relationship, with continued improvements at higher step counts.

At 10,000 steps per day, additional gains include a 7–10% further reduction in all-cause mortality and dementia risk compared to 7,000 steps. At 12,000 steps, the maximum reductions reach up to 55% for all-cause mortality and 12% for cancer incidence, with sustained benefits for dementia and depressive symptoms.

The study also provides some novel insights through subgroup analyses. Younger adults (<60 years) may require 8,000–10,000 steps for optimal benefits, while older adults (≥60 years) see most gains at 6,000–8,000 steps.

Personally, I’ve long targeted around 7,000 steps per day in addition to structured exercise like running or cycling. Research suggests that background activity enhances the benefits of formal workouts; low-step days (<5,000) may hinder exercise adaptations, while higher incidental steps support recovery and metabolic health. This study reinforces that approach, particularly with the significant risk reductions at 10,000–12,000 steps, which likely reflect a blend of intentional and incidental movement (though this is speculative).

The 10,000-step goal, often criticized as arbitrary due to its origins in a 1960s Japanese pedometer campaign, remains appealing as a clear, memorable target. However, any prescribed number—7,000 included—is somewhat arbitrary, chosen for its balance of evidence and feasibility. Some argue for lower recommendations to ensure accessibility, noting that 10,000 steps can feel daunting or unachievable.

I take a different view.

Preventing major diseases like CVD, dementia, and diabetes requires effort, especially as we age. Setting ambitious targets, such as 10,000 steps, could maximize health benefits by encouraging lifestyles that significantly reduce disease risk. While lower thresholds like 4,000 steps are a valuable starting point for beginners, public health messaging should inspire progress toward evidence-based optima rather than settling for the bare minimum gains. Besides, I’m not yet convinced that setting “unrealistic” targets hampers attempts to achieve them.

As a reader of this newsletter, you probably don’t need convincing to “walk more.”

But it never hurts to have some reinforcement.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Thank you for that. My question is how to impute other activities in addition to walking. I go up and down steps at least 10x a day without my phone and swim daily (without my phone) and workout with my phone stationary not on me. I’m hoping walking 5k and other activities will hit a sweet spot.

Excellent presentation of health benefit thresholds from steps