Physiology Friday #282: Why Athletes Need Low-Intensity Training

There's truth behind the advice "run slow to run fast."

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Quickly: My good acquaintance Brad Culp is swimming the Chicago River to fundraise to support ALS research, as well as provide swim lessons for Chicago's underprivileged youth. He’s a good guy (and a great triathlete), so if the spirit moves you, maybe send a few dollars his way to support a good cause (and a crazy guy).

Details about the other sponsors of this newsletter, including Ketone-IQ, Examine.com, and my book “VO2 Max Essentials,” can be found at the end of the post. You can find more products I’m affiliated with on my website.

Elite runners, cyclists, and triathletes—the fastest athletes on the planet—spend an extraordinary amount of time training at what seems like an "easy" pace. Logic (and evidence) would suggest that training closer to race pace or at higher intensities would yield better performance. Yet, athletes across the board continue to pile on miles of slow, low-intensity training. Why is this the case?

A recent perspective article dives into this fascinating paradox. It presents seven intriguing hypotheses explaining why low-intensity training might be the secret sauce behind elite endurance performance, including one hypothesis that low-intensity training may in fact be replaceable.

This one got me to think about—and even question—some of my preconceived notions about why we “run slow” (and why it’s so important).

Understanding the Paradox

At first glance, low-intensity training doesn't seem very stimulating, especially for athletes whose bodies have already adapted to high levels of fitness. Low-intensity training is defined by efforts below the lactate threshold, and generally doesn't significantly challenge the cardiopulmonary system (the heart and lungs) of well-trained athletes. That comes from moderate- (threshold) and high-intensity training.

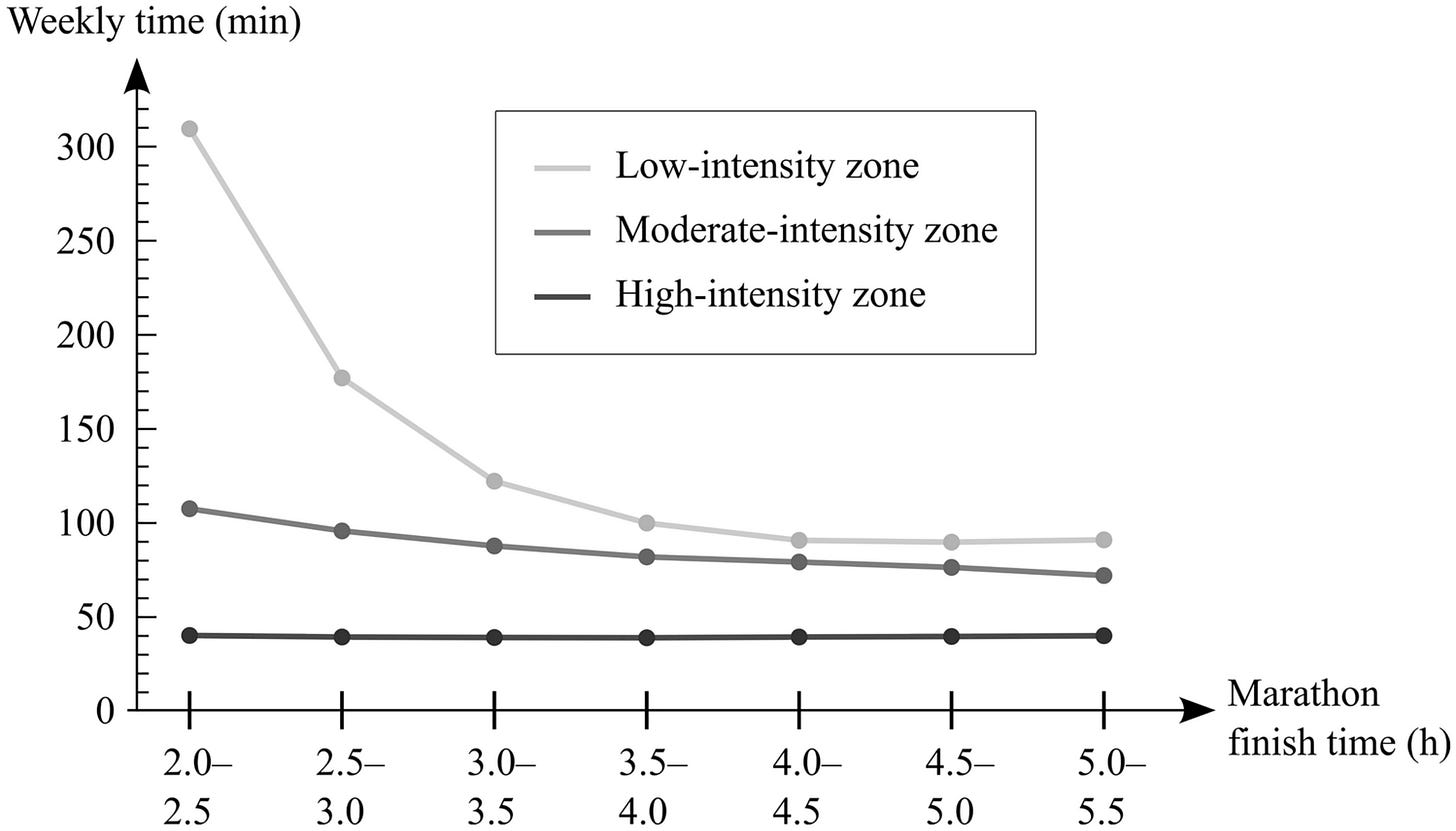

Yet, data from marathon runners show that athletes with faster finishing times spend far more time in the low-intensity zone compared to their slower peers. This is somewhat confounded by the fact that most faster athletes generally spend more time training overall. But it begs the question why elite athletes don’t invest their larger allotment of training into moderate- and high-intensity training, those intensities that actually lead to beneficial adaptations?

This suggests there must be hidden benefits at play, and that's exactly what this new article explores.

The Seven Hypotheses

1. Low-intensity training provides fitness maintenance without stress

One of the simplest explanations is that low-intensity training allows athletes to maintain or slightly improve their fitness without accumulating significant stress. High-intensity training sessions, while incredibly effective, require prolonged recovery—up to two days for complete cardiac autonomic recovery. In contrast, low-intensity workouts typically require less than 24 hours, allowing athletes to train frequently without compromising recovery or risking burnout. Most of us (elite or not) can’t do more than a few hard training sessions per week. And we’ve gotta fill those other days with something, right?

2. Low-intensity training provides alternative molecular signals

Different training intensities activate different molecular pathways. While high-intensity training primarily triggers metabolic stress pathways (it elevates lactate, for example), low-intensity training might stimulate adaptation through fatty acid metabolism and calcium fluxes. By diversifying the adaptation pathways, low-intensity training could enhance overall endurance capacity through complementary mechanisms (there’s a neat little protein called PGC-1 alpha that’s centrally involved here. I’ll spare you the details).

3. Low-intensity training has unique long-term structural adaptations

Consistent, high-volume, low-intensity training over years or decades might facilitate profound structural adaptations. These include increased left ventricular size, greater capillary density, a higher proportion of economical slow-twitch muscle fibers, and expanded mitochondrial mass—all of which enhance endurance performance over a long athletic career. There's even the idea that low-intensity training might preferentially enhance the efficiency of our mitochondria to produce energy, while higher-intensity training preferentially stimulates the production of more or denser mitochondria.

4. Unknown performance factors (we just haven’t measured enough)

As it goes with science, there may be elements of endurance performance enhanced by low-intensity training that we simply haven't measured yet. Factors like durability (a.k.a. "physiological resilience", the ability to resist deterioration of one’s physiology over prolonged running events) and rapid recovery might be significantly bolstered by extensive low-intensity training. (More on this later)

Run Long, Run Healthy is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

5. Low-intensity training benefits psychology and recovery

Let's face it—training hard all the time (while fun) is mentally taxing. Low-intensity training offers a psychological break, reducing mental fatigue and distress. This mental relief might be critical in maintaining an athlete's motivation, consistency, and overall training quality over time.

6. Low-intensity training enhances high-intensity adaptations

Surprisingly, low-intensity training might actually boost the effectiveness of high-intensity workouts. It prepares the body to absorb and recover from intense training by improving baseline fitness and ensuring that the body doesn't resist further adaptations. Essentially, low-intensity training sets the stage for high-intensity efforts to be more effective.

The recovery aspect is something that intrigues me. There's good evidence that combining low-intensity activity (by simply increasing one's daily step count) enhances endurance training adaptations compared to the same training program with fewer steps or more sedentary time outside the context of training. Low-intensity activity might not stimulate beneficial adaptations per se, but rather, augment the benefits of moderate- or high-intensity training sessions.

7. Low-intensity training is potentially replaceable

An intriguing, albeit controversial, hypothesis is that perhaps low-intensity training is replaceable. With optimal programming and meticulous recovery strategies, athletes might sustain high-intensity training without extensive low-intensity work. However, this comes with risks like increased injury rates and the potential for overtraining, suggesting that low-intensity training serves as a “safety net” for long-term athlete health and career longevity.

Ultimately, the fact that a majority of elite (and even non-elite) athletes include lots of low-intensity training into their programs indicates—to me at least—it may not in fact be “replaceable.” Decades and perhaps centuries of practice prove otherwise. If there were a better way, we’d likely have figured it out by now.

As much as I talk about the hype of zone 2 training, most of my qualms are about the emphasis rather than the lack of efficacy. Low-intensity movement is what defines our species, and the more we do of it, the better off we’ll be, whether we’re training for an Ironman or just training to be the best version of ourselves.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

I did more zone 2 than I’d ever done in my life when I trained for marathon last year and got through my entire training block injury free and smashed my time goal too!

Love this rebuttal to the anti zone 2 stuff with Kristi. Also love that you can argue both sides effectively. Thanks for this.