Physiology Friday #283: Does 'Extreme' Exercise Raise Colon Cancer Risk?

Recent headlines draw premature conclusions about a potential link between long-distance running and precancerous adenomas.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

If you’ve jumped on the creatine bandwagon (who hasn’t) but aren’t sure where to start, I suggest you try out Create—the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of gummies (and yeah…their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands), flavored creatine monohydrate single-serve packets, and a daily performance greens gummy (my personal favorite).

They’re giving my audience 20% off of their order. So stock up!

Details about the other sponsors of this newsletter, including Ketone-IQ, Examine.com, and my book “VO2 Max Essentials,” can be found at the end of the post. You can find more products I’m affiliated with on my website.

Last week, several media outlets—including The New York Times—covered a provocative new “study” suggesting ultramarathoners may face a higher risk of colon cancer. The catch? This study exists only as a conference abstract. It hasn’t been peer-reviewed or published in full. That hasn’t stopped headlines from making it sound like an established fact. Not unusual in mainstream science reporting—but it’s not responsible, either. Some of these headlines (like the one from the NY Post) are laughably disingenuous.

Once a narrative reaches the public, it’s hard to correct it, and fear mongering over a small, yet-to-be-published study does more harm than good.

So, let’s talk about it.

Ultrarunning, marathoning, and colon cancer risk

Dr. Timothy Cannon and colleagues (from the Inova Schar Cancer Institute in Maryland) enrolled 100 endurance athletes aged 35–50 who had completed either at least 2 ultramarathons (≥50 km) or 5 marathons.1 Participants underwent a colonoscopy, and all polyps were reviewed by a multi-disciplinary team. The key outcome was advanced adenomas—polyps >10 mm, with tubulovillous histology, or high-grade dysplasia—these are the ones most likely to become cancerous.

The motivation for the study? Dr. Timothy Cannon, the study’s senior author, explained in a press release that he had “observed multiple young ultramarathoners presenting to our cancer center with advanced colorectal cancer despite having no obvious risk factors. That’s what prompted us to look systematically at this group.” I’m a huge fan of turning an observation into a hypothesis and then systematically studying it. It’s how a lot of interesting (and surprising) scientific findings are unearthed. Kudos to them.

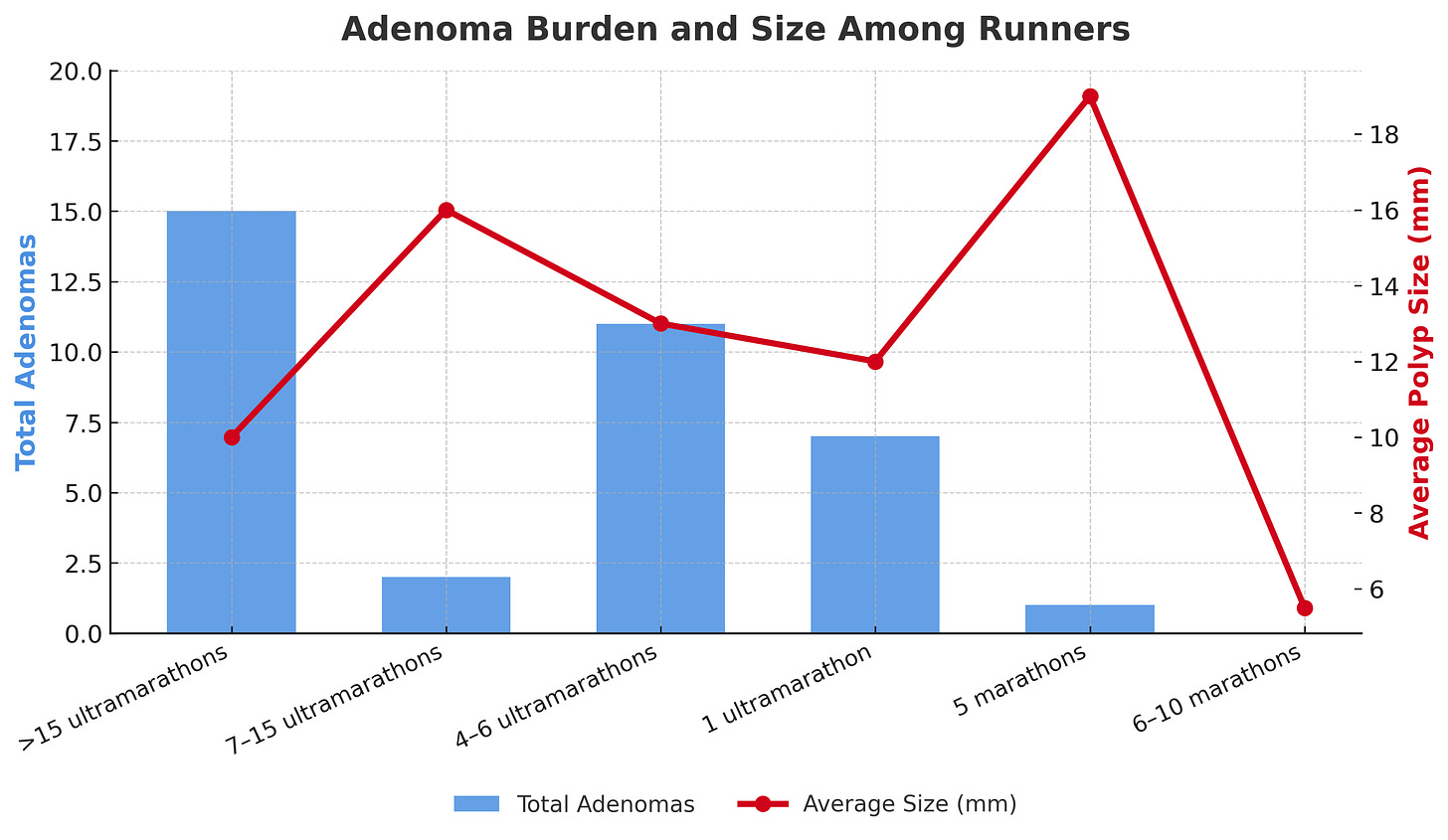

For reference, the expected prevalence of advanced adenomas in average-risk adults 40–49 is ~1.2%. In this runner cohort, 15% had advanced adenomas—more than 10 times higher. Nearly 40% had at least one adenoma of any type. The study’s table of runners with advanced adenomas reveals interesting patterns when broken down by training background. The heaviest ultrarunners (>15 ultras) had the greatest quantity of polyps, while some marathon-only athletes showed the largest individual lesions. Moderate ultramarathon exposure (4–15 races) sat somewhere in between, with concerning average sizes among this group. Here’s a breakdown:

Ultramarathon runners

>15 ultramarathons (5 runners): average polyp size was ~10 mm, but they had the highest total burden with 15 adenomas across the group.

7–15 ultramarathons (2 runners): average polyp size was ~16 mm. They had fewer polyps, but larger ones.

4–6 ultramarathons (3 runners) average polyp size ~13 mm, 11 total polyps.

1 ultramarathon: 1 runner with 7 polyps averaging 12 mm—they were an outlier in sheer number despite relatively low exposure.

Marathon-only runners

5 marathons: 1 runner with a 19 mm polyp (one of the largest in the cohort).

6–10 marathons (3 runners): smaller polyps (5–6 mm) overall.

This shows that risk may express itself in different ways—either more lesions (in the heaviest ultra exposure) or bigger, more advanced lesions (in some marathon runners). Both scenarios increase the potential for progression to colorectal cancer.

Why might extreme running raise risk?

At first glance, this seems to contradict decades of data. The overwhelming weight of evidence says exercise reduces colon cancer risk. A 2016 meta-analysis of 52 prospective studies found physically active individuals had a 24% lower risk of colon cancer compared to sedentary peers. The American Cancer Society, WHO, and multiple national guidelines recognize exercise as a key cancer-preventive behavior.

But extreme endurance training imposes unique stresses. Ischemia during long, hard runs reduces blood flow to the gut and can repeatedly injure the intestinal lining. And while moderate exercise lowers systemic inflammation, ultra-level training could heighten localized inflammation in the gut, which frequent high-volume racing could exacerbate. There’s also “leaky gut” (more formally known as intestinal permeability) that’s caused by repeated stress and made worse by intense exercise in the heat. Chronic GI stress may also impair the absorption of fiber and micronutrients that normally protect the colon. In other words—there is some mechanistic plausibility to these findings.

This brings us to a paradox of exercise and cancer, with the key nuance being dose. Moderate and even high training volumes are overwhelmingly protective against colon cancer. But when training shifts into the realm of chronic ultradistance competition with multiple races per year, the physiology may change. The heart and muscles adapt impressively—but the gut may remain vulnerable to repeated ischemia and inflammatory insults, especially if recovery time isn’t adequate. I don’t know many people who run more than a few ultras per year or even up to 10 marathons.

Let’s be cautious

This abstract certainly raises some interesting questions but leaves several unanswered ones—questions that will paint a fuller picture of this story (the authors note that they plan to publish on participant characteristics like training volume in the future).

For example, could diet confound these findings? We know that (ultra)endurance athletes sometimes eat carb-heavy and calorie-rich diets, which could promote the development of precancerous adenomas or shift the microbiome to a pro-carcinogenic makeup. Were some of these athletes predisposed to colon cancer given their genetics? Perhaps most importantly, do these adenomas even progress to cancer more frequently in runners, or do they stay benign at similar rates?

I can’t help but draw an analogy to findings regarding coronary artery calcium (CAC) in veteran endurance athletes—another seeming paradox of exercise and cardiovascular health. Is the higher prevalence actually due to running “too much” or other factors like diet, alcohol intake, or genetics? And does a higher CAC score translate into worse long-term outcomes for these athletes (i.e., do they get and diet of cardiovascular disease more)?

This study is intriguing, but far from definitive. It was a small study of 100 athletes with no control group. We need larger, controlled, peer-reviewed investigations before concluding that ultrarunning increases colon cancer risk. For now, it’s a reminder that even with something as beneficial as exercise, there may be a point where “more” is not “better.” But let’s wait and see.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.