Physiology Friday #288: Low-Carb Erodes Endurance Performance Gains, Even with Caffeine

Caffeine improves performance across diets—but high carbohydrate availability still wins at race pace.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, and my book “VO2 Max Essentials,” can be found at the end of the post. You can find more products I’m affiliated with on my website.

You don’t see many low-carb or keto athletes dominating the ranks of high-level endurance sports (really, any sport for that matter). And there’s a good reason for this—carbs are king when it comes to exercise performance. When you cut them out, adaptation suffers, and one’s performance ceiling drops…at least that’s what the research shows.

Leading the way in this field is a team headed by Dr. Louise Burke, who, over the last decade of running tightly controlled human studies, has tested versions of “fat adaptation” and ketogenic (low-carb, high-fat or LCHF) strategies in trained and elite endurance athletes.

A consistent pattern is clear—low-carb approaches reliably increase fat oxidation, but at the speeds that decide races (when it really matters), they also increase the oxygen cost of movement (worsen economy) and blunt the normal performance gains from hard training. High-carb strategies, including periodized carbohydrate availability, enable faster training and better race outcomes. Surprisingly, even brief LCHF “blocks” don’t create a later performance rebound once carbs are reintroduced.

One could potentially argue that, in some cases, low-carb and high-carb diets can produce equivalent performance outcomes. One thing is clear, though—low carb is never superior.

Despite some backlash from the low-carb community about inadequate study methods and other “flaws” (the studies are never long enough), the literature paints an unequivocal picture of exercise metabolism. If you want to go hard, you need carbs.

A new study by this group asks something entirely novel and, in my opinion, incredibly practical:1

Could using caffeine reverse some of these changes caused by low-carb, essentially “rescuing” performance impairments seen in previous studies?

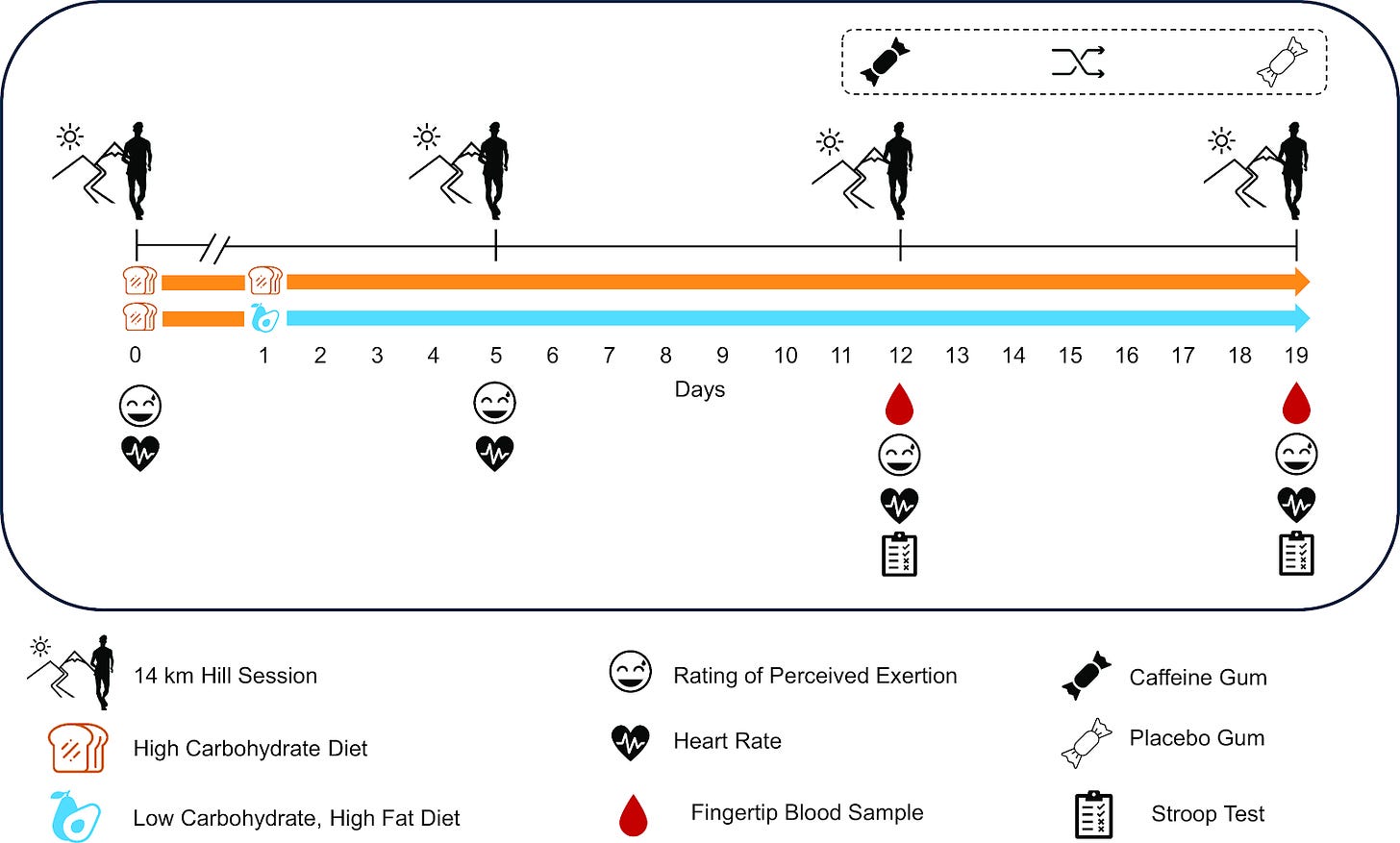

To test this, Burke and colleagues embedded a caffeine–placebo trial inside a 3-week training camp with 21 world-class race walkers.

Everyone began with a baseline 14-kilometer tempo hill session on high carbs (their usual diet). Then, athletes split into one of two energy- and protein-matched diets, but which differed in their carbohydrate content:

High-carb group (HCHO): consumed ~8 grams of carbs per kilogram of body weight per day and ate carbs before and during key training sessions.

Ketogenic group (LCHF): consumed 0.5 grams of carbohydrates per kilogram of body weight per day (less than 50 grams), with 78% of their diet coming from fat. They consumed only water with electrolytes during their training sessions.

Over the next three weeks, they repeated the same 14-kilometer session weekly. The week 1 test was done under normal conditions, but in weeks 2 and 3, each athlete chewed either a caffeine gum (~3 mg/kg of body weight via caffeinated gum) or a placebo. Researchers measured walking speed, intensity (speed) relative to VO₂max, heart rate, perceived exertion, blood metabolites, and even cognitive performance via a Stroop test (more on that later).

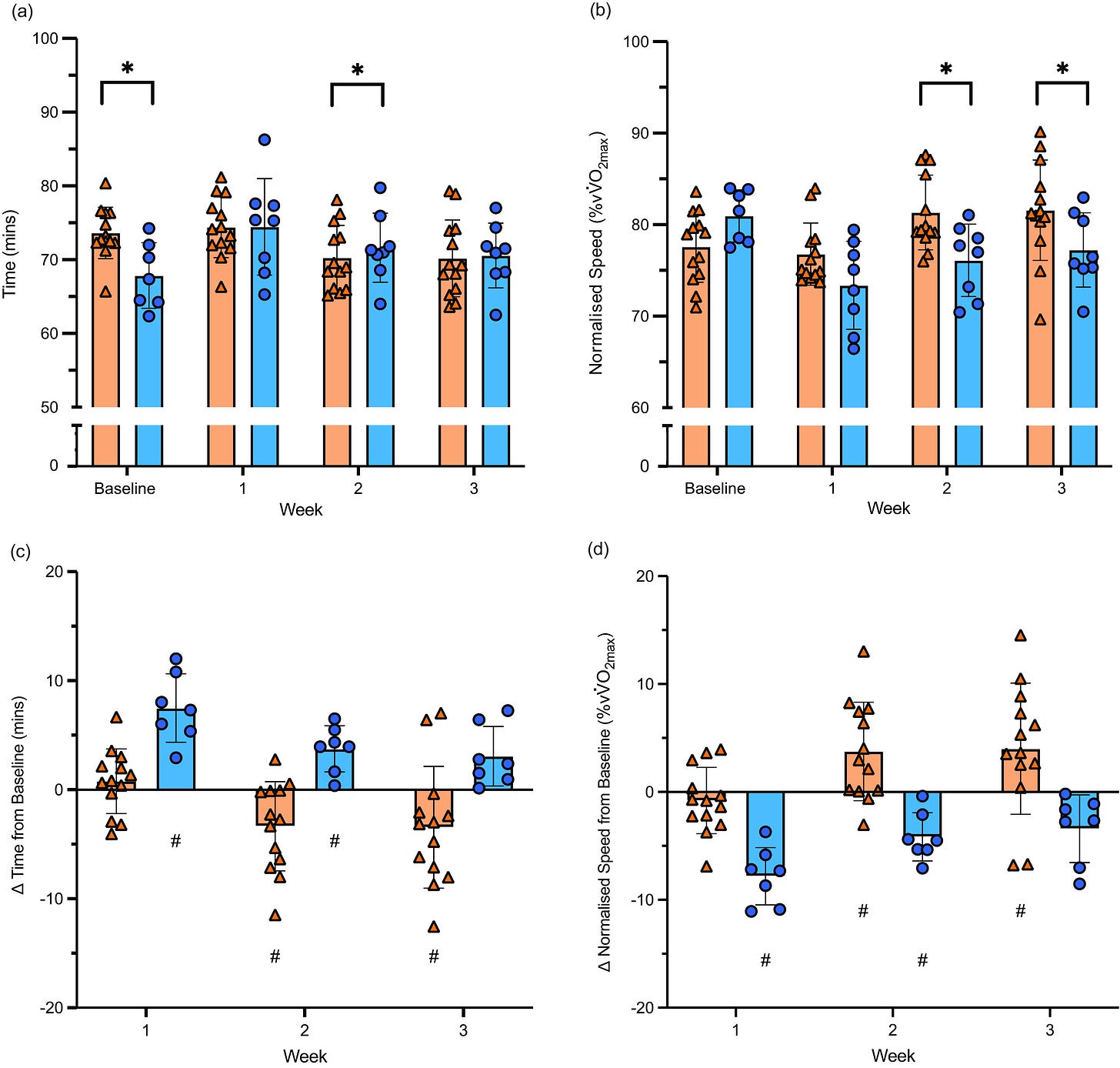

Steady performance declines with low-carb

At baseline, the keto athletes actually held a small advantage—about 6 minutes faster and working at a roughly 3.4% higher percentage of their speed at VO₂max than the high-carb group on the 14-kilometer hill course. This represents a “statistical artifact”—the groups just weren’t balanced at baseline. In fact, it’s entirely explained by the fact that the high-carb group comprised 5 female athletes (and 8 males) while the low-carb group comprised 7 males and just 1 female. Averaged times in the group assigned to low-carb were just faster before the diets began.

Over the next three weeks, LCHF slowed by ~7 minutes in week 1 and ~3 minutes by week 3 versus their own baseline, while HCHO improved by ~3.5 minutes by week 3. When you normalize speed to capacity, the pattern is the same. By weeks 2 and 3, HCHO was training at a 5.2% and 4.4% higher percentage of their speed at VO₂max than LCHF, respectively. The keto group that started faster ended up training slower and at a lower relative intensity, whereas carbs supported steady gains and higher-quality training. And despite moving in opposite performance directions, the sessions felt equally “very hard” for both groups (RPE was the same). Another tell was in the heart-rate trend. The high-carb group’s average heart rate fell from ~170 to ~158 bpm by week 3, a classic sign of improving economy at a given perceived effort, while the low-carb group’s heart rate never showed a comparable drop across weeks 2 and 3.

Enter caffeine…

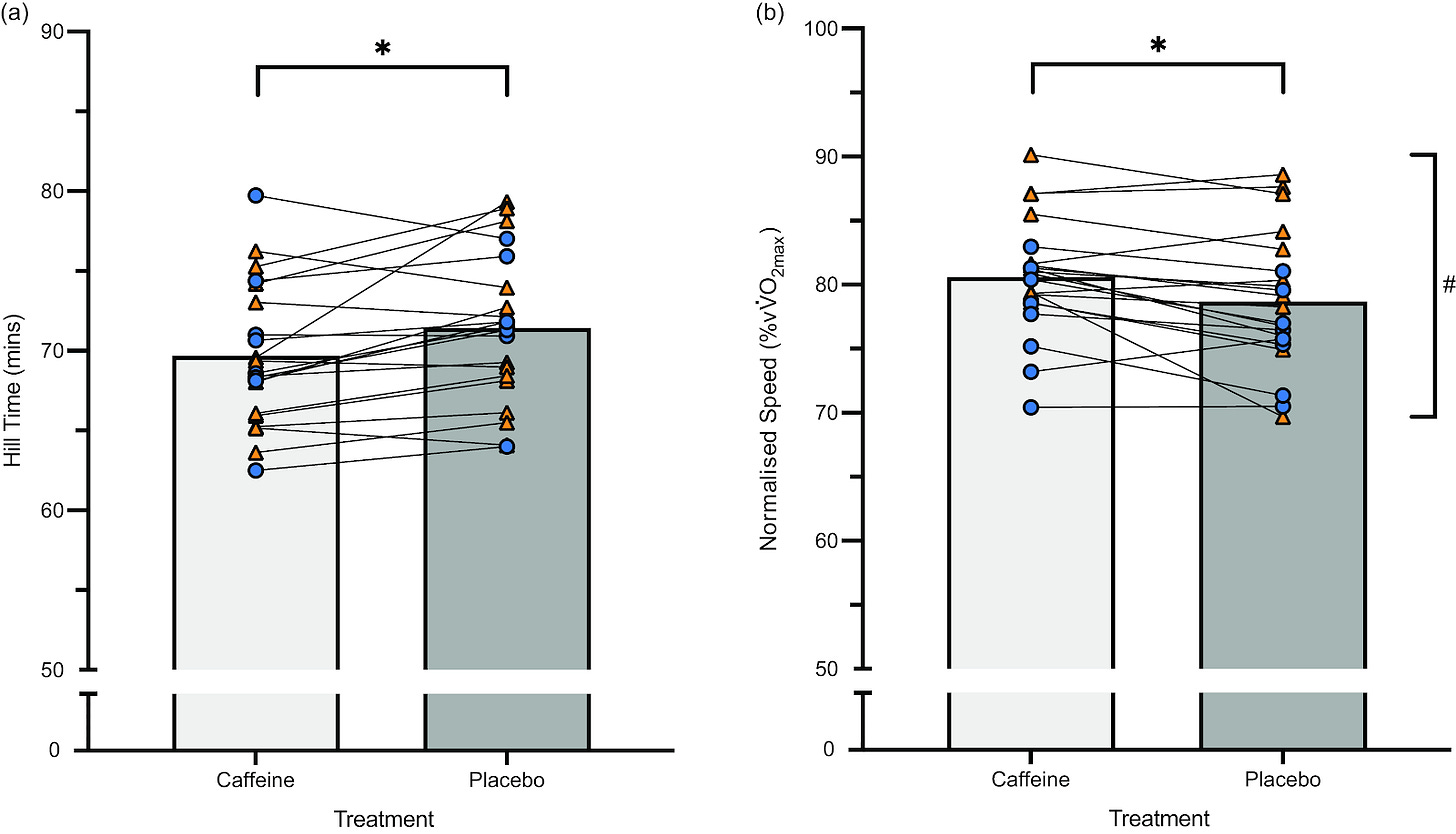

Layering in caffeine didn’t change the hierarchy, but it did move the needle for everyone, improving hill-course time by about 2.4% and lifting relative intensity by ~2.39% versus placebo—an unmistakable performance bump without extra strain (RPE and heart rate were unchanged).

Even so, the fastest combination remained high carbohydrate availability + caffeine. Athletes on LCHF improved with caffeine, but still trained at a lower race-relative intensity than the carb-supported group. In fact, the low-carb group still performed worse with caffeine than the high-carb group did without caffeine (as a brief glance at the top left graph in the figure above shows).

Caffeine boosts cognitive performance after exercise

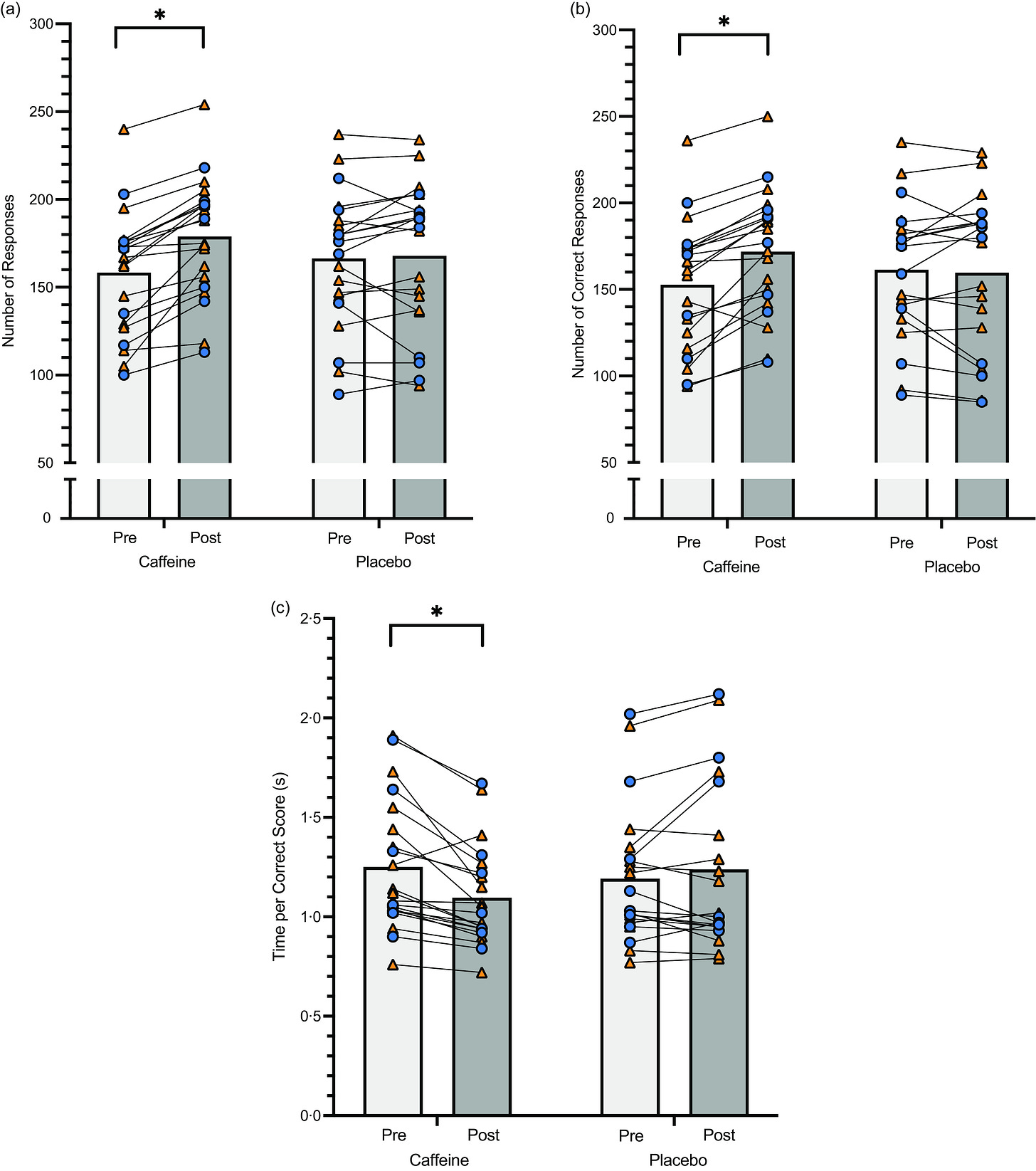

The 3-minute Stroop test—a widely-used test of attention, processing speed, and response inhibition—was run immediately before and after the exercise session and painted a clear picture. With caffeine, athletes finished the workout answering more items overall and more items correctly than they had pre-session, and they did so more quickly per correct response. With placebo, none of those pre- to post improvements appeared. In other words, the session ended with athletes sharper and faster-thinking only when they’d taken caffeine beforehand. However, they didn’t have worse cognitive performance without caffeine, and that’s an important finding too.

These cognitive gains were diet-independent: LCHF and HCHO athletes showed the same direction and magnitude of post-exercise improvements on caffeine, and neither diet showed meaningful pre to post change on placebo (so much for the idea that keto boosts brain power).

Rather than beat a dead horse and talk about the downsides of low-carb that were illuminated (again) in this study, I’ll instead focus on the caffeine component.

Despite caffeine’s well-known ergogenicity, it wasn’t enough to bring the low-carb group’s ceiling back to normal! Not only were they much slower than the high-carb group, but they were also much slower than themselves at baseline (without caffeine), despite an extra 3 weeks of intensified training.

Low carb hurts performance more than caffeine helps it, but if you are low-carb, or perhaps exercising in a fasted or carb-restricted state, the good news is that you can still get a notable performance bump from caffeine.

What I find most interesting about this study is the cognitive boost from caffeine post-workout. We’ve all experienced the post-workout brain fog, especially if it’s hot and humid and the workout was intense. It can take a while for your brain to start working normally again. Well, having a strong dose of pre-workout caffeine (at my weight of ~145 lb, I’d need to take about 200 mg of caffeine) appears to boost brain performance above pre-workout levels. Better attention, quicker processing speed, etc. If you take more caffeine after your workout, you might just have superpowers.

I don’t really have any deep conclusions or insights from this study, but I can offer some very practical takeaways: Low-carb bad. Caffeine good. Low-carb plus caffeine, less bad. Caffeine plus carbs, even better.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 20% off their order. So stock up!

I am curious about this study as a generally low carb athlete. I went low carb 15 years ago when I was training for a natural bodybuilding competition. I appreciated how it helped me lean out and was not difficult to sustain, so I just kept it - in a moderated form. As I went through menopause and since then I have never struggled with the weight gain that many women deal with. And I prefer to run or ride on just coffee with MCT oil and a bit of cream in it. I have taken gel packs during 2-3 hour efforts but have never noticed getting any boost in energy from the sugar. I'm wondering if this is because I'm fat adapted and so do not metabolize the sugar very effectively. I'd love to get some theories on what might be going on. Thanks for the work you're doing.

I traditionally eat moderate amount of carbs. I decided to support my husband and go Keto and limit carbs. The timing worked against the last month on training for a half marathon. I am not speedy but could definitely tell the difference in endurance.