Physiology Friday #289: Have We Underestimated the Health Benefits of Vigorous Activity?

For decades, we’ve assumed that one minute of vigorous activity equals two minutes of moderate activity. But that assumption might be wrong.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, and my book “VO2 Max Essentials,” can be found at the end of the post. You can find more products I’m affiliated with on my website.

Most of us have heard the physical activity recommendations by now: aim for 150 to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week, or if you’re short on time (perhaps you prefer to call it “efficient”), 75 to 100 minutes of vigorous-intensity (or high-intensity) activity.

In other words, you can do more at a lower intensity or less at a higher intensity and still achieve similar health benefits—whether that’s improved metabolic health, a higher VO2 max, or a lower cardiovascular disease risk (a few of the many reasons to exercise).

It’s a trade-off we’ve accepted for years, and it’s based on the assumption that one minute of vigorous activity equals two minutes of moderate activity.

But that assumption might be wrong.

Despite these recommendations, only about 20–25% of adults actually meet them. And even among those who do, we still don’t fully understand the optimal amount of physical activity for health or whether there’s a point of diminishing returns. What we do know is that something is better than nothing, and more is generally better than less.

The current equivalence between vigorous and moderate exercise is based primarily on energy expenditure—the calories burned per minute of exercise that’s often described in terms of metabolic equivalents of task or METs. Because you burn roughly twice as many calories doing vigorous exercise as you do during moderate exercise, it makes sense to say that one minute of vigorous exercise equals two minutes of moderate. But health outcomes aren’t determined by calorie burn alone.

Physical activity exerts its benefits through complex physiological and molecular pathways, from cardiovascular remodeling to hormonal and inflammatory changes, that energy expenditure can’t fully capture. It’s one of the reasons I frequently push back against the narrative that low-intensity activity like walking is sufficient for optimal health. It’s just not true.

Now, research is challenging this long-standing assumption. Using device-measured activity data (rather than self-reports, as previous studies implemented), a new study finds that vigorous activity may be exponentially more beneficial for health outcomes like cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes than we previously thought. The findings could change not only how we think about exercise but how we write public health recommendations altogether. So let’s dig in.1

The study was part of the UK Biobank, one of the largest and most detailed biomedical databases in the world. It included 73,485 adults who had valid data from 7 days of continuous wrist-worn accelerometry (activity tracking), meaning their movement intensity could be measured objectively and continuously throughout the day. Participants were then followed for an average of 8 years using national health registries to track major outcomes, including all-cause mortality (death from any cause), cardiovascular disease mortality and events (e.g., heart attack, stroke, heart failure), type 2 diabetes, and cancer mortality and incidence.

The analysis adjusted for dozens of lifestyle and demographic factors, including age, sex, smoking status, alcohol intake, diet, sleep, medication use, and family history—those confounding variables that might introduce noise into the data and skew the results. It also excluded participants who developed disease early in follow-up to minimize the chance that poor health influenced physical activity levels (a problem known as reverse causation).

Three activity intensities were defined:

Light-intensity activity (LPA): slow walking, household chores, etc.

Moderate-intensity activity (MPA): brisk walking, cycling at an easy pace.

Vigorous-intensity activity (VPA): running, climbing stairs quickly, or anything that makes breathing rapid.

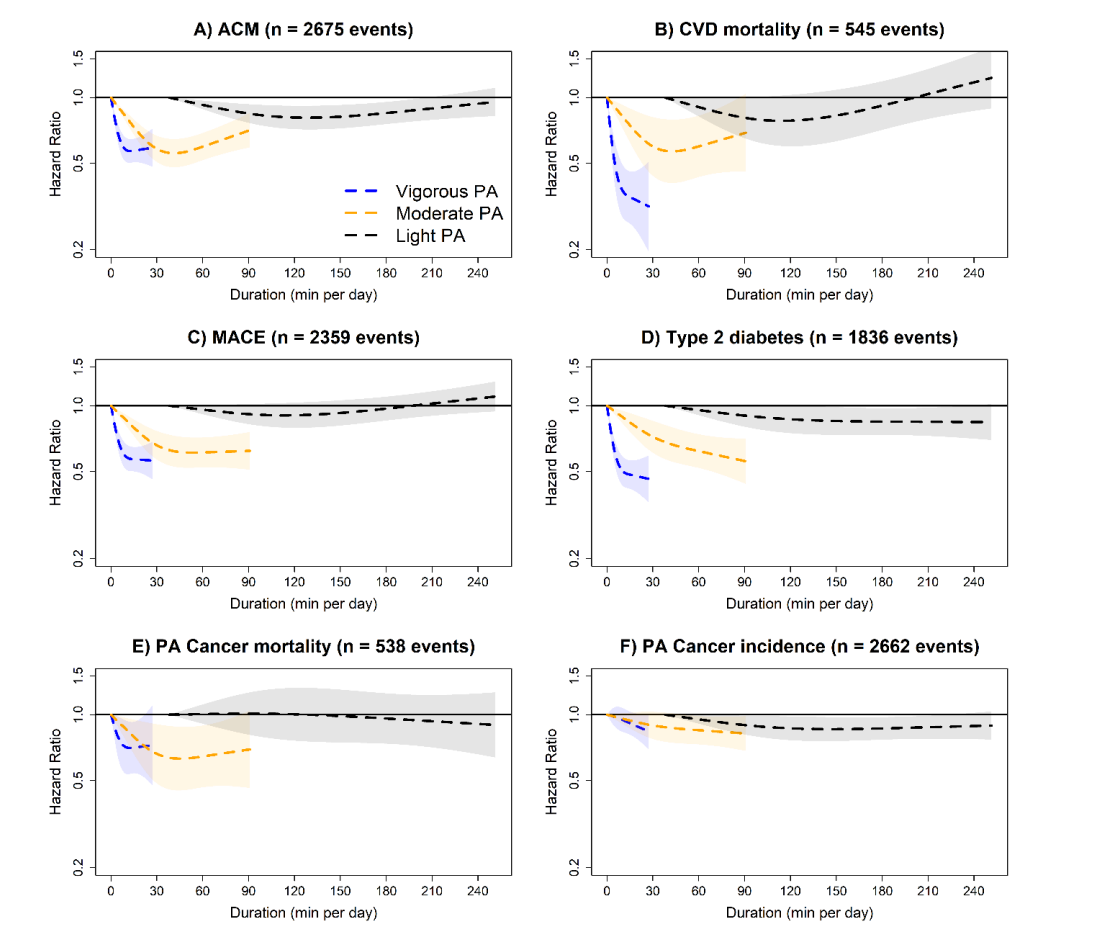

When researchers mapped how disease risk changed with increasing amounts of physical activity, a clear pattern emerged: intensity matters. Vigorous activity produced the steepest and most consistent declines in disease risk (sometimes with little evidence of a plateau at higher volumes), moderate activity offered meaningful but smaller benefits that began to plateau at higher levels, and light activity provided only modest improvements, even at very large volumes, rarely reaching statistical significance.

For all-cause mortality, each increase in vigorous activity was associated with a nearly linear drop in risk—people who regularly engaged in higher-intensity movement had roughly 30–40% lower risk of premature death compared to those who did little to none. Moderate activity also reduced mortality, though its benefits began to flatten after about 30–40 minutes per day (yielding around a 15–20% risk reduction). Light activity, on the other hand, provided smaller returns—requiring hours of movement to achieve only a 10–15% lower risk of death.

When it came to cardiovascular outcomes—including both cardiovascular mortality and major events such as heart attack and stroke—those who accumulated the most vigorous activity had roughly 35–40% lower cardiovascular risk, compared to 20–25% for high amounts of moderate activity and again, only minor benefits from light activity.

For type 2 diabetes, intensity again dominated. Vigorous activity showed some of the strongest associations in the study, with the most active individuals experiencing up to 40–50% lower risk of developing diabetes. Moderate activity provided noticeable but slower gains (around 20–25% lower risk at higher volumes) while light activity produced only modest improvements.

Finally, the relationships with cancer outcomes were generally weaker but still notable. Vigorous activity was linked to roughly 20–25% lower cancer mortality, while moderate activity yielded smaller reductions, and light activity showed minimal impact. For overall cancer incidence, the trends were even flatter.

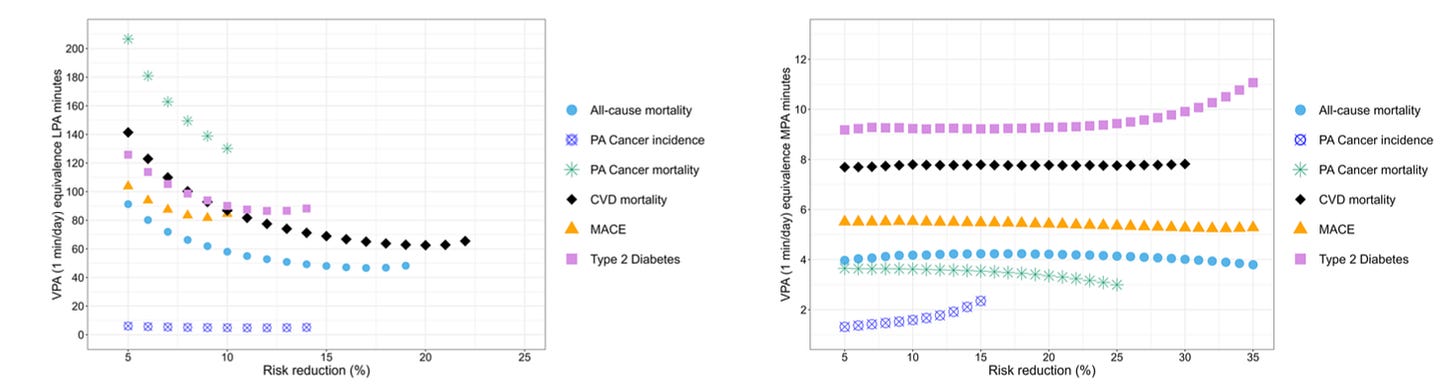

Health equivalence of vigorous, moderate, and light activity

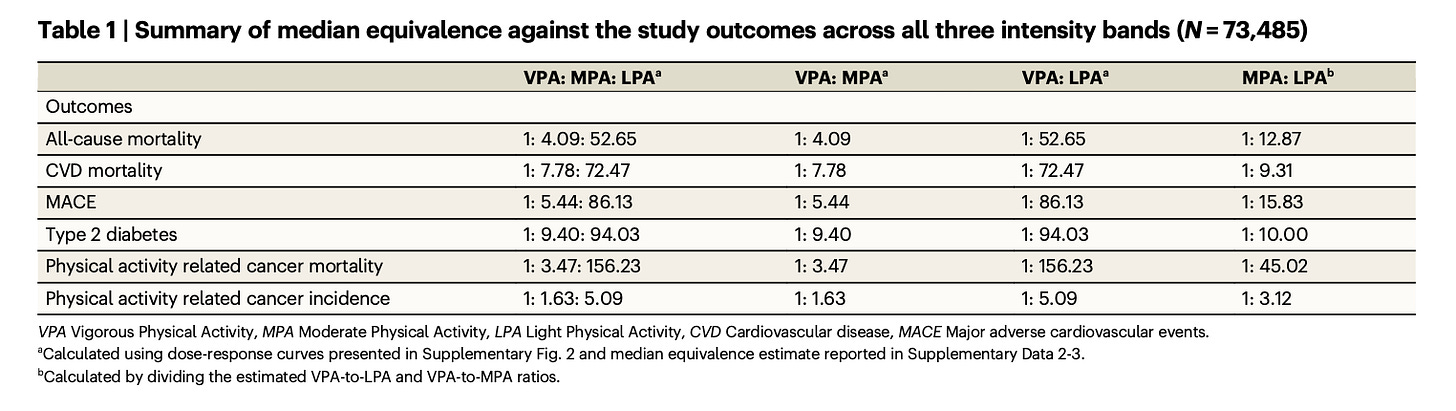

Instead of assuming a 1:2 equivalence between vigorous and moderate activity, the researchers directly calculated how many minutes of MPA or LPA were needed to achieve the same 5–35% reduction in disease risk as one minute of VPA. That ratio—expressed as “minutes of MPA (or LPA) per 1 minute of VPA”—is what they call the health equivalence ratio.

For every 1 minute of vigorous activity, it took 4 to 9 minutes of moderate activity to achieve the same reduction in risk for major outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and all-cause mortality. It took a staggering 53 to 156 minutes of light activity to achieve the same effect, depending on the health outcome.

To put it in simpler terms, the traditional 1:2 equivalence ratio is way off. Vigorous activity appears to be 2 to 4 times more potent than old assumptions suggest.

Here’s a breakdown of the findings by outcome:

For all-cause mortality, every 1 minute of VPA equated to roughly 4 minutes of MPA or 53 minutes of LPA.

VPA was even more powerful for cardiovascular disease mortality and events. 1 minute of VPA was equivalent to ~8 minutes of MPA or 73 minutes of LPA.

For type 2 diabetes, 1 minute of VPA corresponded to roughly 9 minutes of MPA or 94 minutes of LPA for equivalent risk reduction.

The pattern was weaker but still present for cancer-related outcomes. 1 minute of VPA equaled about 3.5 minutes of MPA for cancer mortality, and the equivalent ratio for cancer incidence was closer to 1.5 minutes.

If you’re someone who prefers lighter or moderate exercise, that’s still great—but this study suggests you may need to do far more than you think to achieve the same biological and physiological benefits as a smaller dose of vigorous activity.

We know from physiology why this makes sense. High-intensity exercise produces greater vascular shear stress, drives up hormonal and neurotransmitter responses, and, perhaps most importantly, triggers cardiac adaptations like improved stroke volume and maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂ max). These are adaptations you simply don’t get (or don’t get as efficiently) from slower, lower-intensity movement, regardless of how much you do! It’s why elevating your heart rate close to its maximum at least once per week may be critical for long-term cardiovascular health.

So, while walking is wonderful—and it absolutely has a place in every health routine (including mine)—we shouldn’t fall for the comforting narrative that “walking is all you need.” The biology tells us otherwise. As the study authors put it, “not even the largest amounts of daily light activity can elicit the beneficial effects of moderate or vigorous intensities.” Our bodies (and probably our minds) crave the stimulus that only higher-intensity movement provides.

From a public health standpoint, this creates a dilemma, because on one hand, these findings suggest we may need to raise the bar for what’s considered sufficient physical activity. On the other hand, only about 20% of people currently meet our already low guidelines. Raising them further might only widen the gap between recommendation and reality.

Perhaps the most practical path forward is to update how we talk about equivalence, recognizing that it’s not a one-to-one (or even a one-to-two) trade-off. Vigorous activity packs a much greater punch, and guidelines should reflect that. Fortunately, modern wearables now make it easier than ever for us to monitor our activity levels and intensity zones, turning data like this into actionable feedback that can be used on a personal level (and as this study shows us, on a public-health level too).

We don’t always need to move more to get healthier. Sometimes we may just need to move harder (though more is helpful too).

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 25% off their order. So stock up!

From my interpretation, their VPA category sounded like more base/z2 efforts, which we all know is beneficial. In my mind when I hear the word “vigorous” I always think threshold workouts or above. Either way, data still holds, need to up the intensity to experience more adaptations.

This was a timely post. I have a foot issue I’m dealing with so I had to curtail my rucking and running and supplement with HIIT sessions using sandbags and kettlebells between my twice-weekly resistance training.

Unlike an hour or rucking, these HIIT sessions are usually 20-25 minutes and I’m gassed. The amount of time I’m spending exercising per week has gone down but the intensity feels much higher (which I know is subjective).

The other thought I had reading this is if done right, all our days should ideally be a mix of LPA, MPA and HPA. I don’t know how to convey that from a policy perspective. We’re so much an all or nothing society, always looking for the next hack or optimization. As you and others have written, we’ve made “exercise” this separate thing from our day to day that it’s an extra thing people must do instead of something that’s part of their lives.