Physiology Friday #296: Can Excessive Exercise Cause Cognitive Decline?

A specific muscle-to-brain pathway explains why overtraining may sap the brain's valuable energy reserves.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter and deals on products, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, Equip Foods, Consensus, and ProBio Nutrition can be found at the end of the post.

Exercise is good for your brain.

This is one of those undisputed statements in exercise physiology and health.

In fact, the other day I posted on X that “Physical activity is perhaps the best defense we have against Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline.”

Furthermore, engaging in exercise—in particular, high-intensity interval training—enhances brain blood flow and acutely improves cognitive performance, in part due to high levels of lactate stimulating the production of a brain growth factor called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the brain (if you want the best overview of exercise and BDNF, check out Dr. Rhonda Patrick’s content).

But what if it’s not always the case that more is better? Earlier this year, I covered a study showing that running a marathon causes the loss of myelin (the protective coating around neurons) in the brain. Up to a 28% drop in myelin was observed in critical white matter regions that didn’t fully recover for up to 2 months post-race.

This begs the question. What if too much vigorous exercise doesn’t just stop being helpful, but actively harms cognition?

A new study shows that this might be true, and it happens via a very specific muscle-to-brain signaling pathway.1

The J-shaped curve: How much exercise is too much?

The paper starts at the population level, using the UK Biobank—a cohort of over half a million adults with detailed lifestyle, health, and cognitive data. The authors analyzed 316,678 people with complete information on physical activity and cognition. Physical activity volume was quantified in MET-minutes per week (MET = metabolic equivalent, a measure of physical activity intensity).

They found two key patterns:

1. More activity is generally good—up to a point. Total physical activity showed a J-shaped association with the risk of cognitive impairment over a median of ~14 years of follow-up. Risk fell as activity increased, hit a minimum around 3,972 MET-minutes per week (where the risk of cognitive impairment dropped by about 27%), and then started creeping back up at the very high end.

2. When the authors zoomed in on vigorous activity specifically, the “sweet spot” was 1,216 MET-minutes per week, again corresponding to about a 27% lower risk of cognitive impairment. Beyond that, the curve bent back upward.

They then stratified by sex and age and saw the same J-shape, with the lowest risk of cognitive decline occurring at different activity levels for certain groups:

Women: 1,013 MET-min/week of vigorous activity

Men: 1,368 MET-min/week

Adults ≥65: 1,165 MET-min/week

Adults <65: 1,418 MET-min/week

Two things are worth emphasizing here. First, roughly speaking, 1,200 MET-min/week of vigorous activity is in the ballpark of ~200 minutes per week of something like hard running, rowing, or intervals, depending on the assumed MET value. That’s already near the top end of WHO’s recommended 75–150 minutes/week of vigorous activity—and the authors note that only a minority of people in the cohort exceeded the “optimal” range. Second, for moderate-intensity movement, the curve was much flatter. Once people crossed the moderate sweet spot, risk didn’t shoot up in the same way it did for vigorous activity.

So at the epidemiological level, the signal is that moderate exercise is broadly safe and beneficial; extremely high volumes of vigorous exercise might be a different story.

But observational data can’t tell us why this happens. For that, the study turned to mice.

Researchers put mice through a 12-week treadmill exercise program, carefully quantifying workload using METs to mirror the human data. They defined moderate exercise as 281–563 MET-min/week and excessive vigorous exercise as vigorous-intensity of more than 450 MET-min/week—that’s where the cognitive benefits flipped to harm in the dose-response experiments.

Mice in the excessive groups (the “overtrained mice”) performed worse on both spatial and non-spatial memory tests after the training. Basically, learning and memory were worse compared to the control mice performing normal levels of exercise.

Overtrained mice also had clear structural damage to their hippocampus (the brain’s key learning and memory hub), with reduced density of dendritic spines, lower levels of synaptic proteins, and shortened postsynaptic density length—all markers that the brain’s communication networks were impaired.

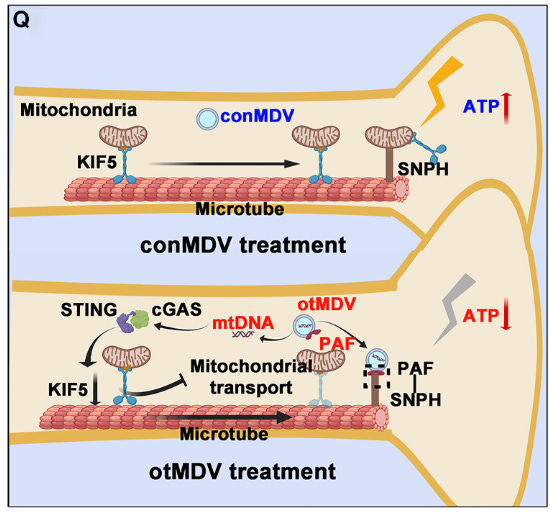

How does stress in skeletal muscle end up stripping synapses in the brain? The surprising culprit in all of this was something the authors term “mitochondrial pretenders.” And this is where the study gets fun. It identifies a subpopulation of mitochondria-derived vesicles (or MDVs) that are released from overworked muscle and travel to the brain.

MDVs are small extracellular vesicles that specifically package pieces of mitochondria. They’re an emerging mechanism for mitochondrial quality control and inter-organ communication.

Excessive vigorous exercise did several things to skeletal muscle mitochondria: it led to noticeably swollen mitochondria and several indicators of heightened MDV production. And the MDVs from overtrained mice were distinct from those of the control mice. They were enriched in mitochondrial proteins and had more mitochondrial DNA than typical; they “leaked” into the brain across the blood-brain barrier; and they were causally harmful. Injecting the “overtrained” MDVs into healthy mice was sufficient to impair cognitive performance and elevate markers of synaptic dysfunction in the hippocampus. Conversely, blocking MDV secretion from muscle protected excessively exercised mice from cognitive decline and synaptic loss.

Next up was figuring out exactly how these “mitochondrial pretenders” harm synapses in the brain. Well, synapses rely heavily on local mitochondria both for ATP production and for calcium buffering. Two processes are critical for this to happen: transporting mitochondria to the synapses and anchoring them to the synapses.

The “mitochondrial pretenders” (the “overtrained” MDVs) attack both of these processes: they downregulate the motor proteins that are crucial for transporting mitochondria along axons in the brain, and they displace “real” mitochondria from anchoring sites on synapses.

The result is straightforward. Synapses lose their on-site energy factories, creating an energy deficit in the brain.

Lactate is the source of “mitochondrial pretenders”

What triggers a muscle to start mass-producing these mitochondrial pretenders in the first place? The authors focus on lactate, which rises sharply with intense exercise.

Excessive vigorous exercise in mice drove substantial lactate accumulation in muscle tissue. And when they injected high-dose lactate directly into muscle, they reproduced the key features of excessive exercise. However, simply mimicking high blood lactate levels did not trigger the same MDV response. It was local lactate buildup in muscle, not just elevated systemic lactate, that mattered.

This pathway links intramuscular metabolic stress—specifically, excessive lactate buildup during high-intensity loads—to the production of these vesicles that can reach the brain and disturb synaptic energy production.

It’s important because it indicates that lactate is not inherently bad. At moderate levels, lactate acts as both a fuel and a signaling molecule that can support brain function. This study is about what happens when lactate accumulates in muscle past a certain threshold repeatedly, in the context of chronic excessive vigorous training.

Human evidence of the harms of excessive exercise

Results in mice are only half the story (and arguably the least interesting to human readers). Luckily, this study also asked whether we see similar signals in humans actually performing exercise.

In a small acute-exercise study, researchers recruited people performing badminton, running, and weightlifting.

Blood was drawn immediately after exercise. Across all three activities, there was a significant positive correlation between plasma lactate levels and circulating MDVs (more lactate = more MDVs).

So in humans, as in mice, harder efforts with higher lactate are associated with higher levels of these potentially harmful vesicles.

More compelling was a 6-week randomized controlled trial in which 40 participants were randomized to a moderate-duration vigorous exercise group (who performed 1,000 MET-min/week or about 150 minutes of vigorous exercise) and an excessive vigorous exercise group (who started at 150 minutes of vigorous exercise per week and increased up to 450 minutes per week by the end of the study).

After 6 weeks, both groups had higher lactate after training, but increases were significantly larger in the excessive group. Only the excessive group showed marked increases in MDVs and mitochondrial DNA in those vesicles. The authors also measured something known as the N-acetyl-aspartate to creatine ratio (NAA/Cr) in the hippocampus—a marker of neuronal health. This ratio fell in the excessive group, consistent with neuronal distress, but not in the control group.

On cognitive testing, participants in the excessive group showed declines in fluid intelligence and numeric memory scores, while the moderate group did not.

Changes in the MDVs (those “mitochondrial pretenders” induced by excessive vigorous exercise) negatively correlated with changes in cognitive performance, even after adjusting for other factors like cortisol, BDNF, and an inflammatory marker called IL-6. MDVs emerged as an independent risk marker for cognitive dysfunction.

The full human picture looks like this:

Very high volumes of vigorous exercise in big observational cohorts are linked to higher risk of cognitive impairment.

Acute human exercise elevates both lactate and MDVs in a dose-dependent way.

Pushing people into an “excessive” vigorous training zone raises MDVs and subtly impairs cognitive performance over just six weeks.

At this point, it’s natural to ask: Should I be worried about my training harming my brain?

My take? Probably not. But there are a few key points of context.

Most people are not in the danger zone. In the UK Biobank data, only a relatively small fraction of participants exceeded the optimized vigorous-exercise threshold. The majority of the population is well below even the “sweet spot,” let alone the “too much” category. But chances are, if you’re reading this, you’re closer to the far right of the exercise threshold than most people (just a hunch).

Furthermore, moderate exercise remains unequivocally beneficial. The J-shaped risk curve is steeply protective up to that moderate/vigorous nadir and only bends upward at the far right tail. There’s no signal here that going from inactive to active to moderately vigorous is anything but good for the brain.

Perhaps most importantly, “excessive vigorous exercise” here is specific. In both mice and humans, the authors define precise thresholds using METs and %VO₂max. So this isn’t about someone doing a couple of HIIT sessions per week—it’s about chronic high volumes of near-maximal effort with substantial intramuscular lactate accumulation, sustained over weeks to months. What one might consider to be true overtraining (a rare but not unachievable phenomenon).

One novel aspect of this study is that it suggests that these MDVs could serve as a biomarker for individuals at risk of exercise-induced cognitive impairment. In humans, measuring MDVs might eventually help distinguish between “healthy” vigorous exercise training and “excessive” training that’s beginning to stress the brain rather than benefit it, even before overt symptoms of cognitive dysfunction appear.

Practically, for highly active people and athletes, I think this study supports the intuition that yes, exercise is good, but there’s likely a ceiling to productive high-intensity volume when it comes to the brain (just as there likely is for cardiovascular health or performance).

As always in physiology, it comes back to dose.

Exercise is medicine, but like any medicine, the dose and schedule matter.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 30% off their order this week. So stock up!

ProBio Nutrition—the all-in-one supplement that I use every single day—is offering 20% off. My preference is the tangy orange flavor, but they also sell an unflavored “smoothie booster” that’s great in a shake, smoothie, or juice.

Equip Foods makes some of the cleanest, best-tasting protein products around. I am absolutely obsessed with their Prime grass-fed protein bars (the peanut butter ones are to die for). Take up to 10% off site-wide!

Consensus is the AI-powered research engine that I use daily to stay up to date on the literature and make sure I’m covering the latest and most rigorous science. They’re giving my audience 1 month of premium for free.

Hello Brady, there is some kind of difficulty for a non English speaker to translate moderate and vigorous since I feel like these two words mean something lighter that I would intuitively think of. In Medicine, we use a lot the 4 MET threshold. It’s just two flights of stairs !

When we recreationnal athlete do interval training we can hover in 12-16 MET range for 10-30 minutes usually. That’s between 120 and 480 MET-mins for one interval workout without warming up and cool down…

So saying that 1200 MET-mins/wk is a threshold in athletes seems odd to me. I guess we, athletes, have developed some fortitude in the muscle used to deal with metabolic stress. 1200 seems like 3h20 minutes of light jog to me… am I wrong ?

Thanks

Ok…I’m not nearly as smart as you guys 😂…just a 61 year old dude hoping I’m not hurting myself by training, in my opinion , fairly hard.

My tracking app shows me a MET value of 10.4 for my 86 minute trail run. Does that mean 894 Met/Min just for that workout? If additional data helps with context, my Average Power shows 232w