Physiology Friday #297: Post-Workout Hot Baths Provide a VO₂max Boost

Passive heat training is altitude in disguise.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter and deals on products, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, Equip Foods, Consensus, and ProBio Nutrition can be found at the end of the post.

Heat training is suddenly everywhere, not just in endurance circles, but across the broader “health optimization” world too.

People are experimenting with heat suits, layered workouts, post-training saunas, and hot baths, all chasing a certain goal. For some, that goal is longevity or a lower risk of dementia (which heat shock proteins promise to deliver). For others, it’s a healthier, stronger heart. For athletes, it’s often greater strength gains or more aerobic adaptation without necessarily doing more pounding, more volume, or more high-intensity work.

For now, we’ll focus on aerobic adaptations. And the appeal of heat training here makes sense… if you can elevate VO₂max (and overall aerobic capacity) by adding a thermal stressor instead of piling on more mechanical stress with training, that’s a meaningful lever for both performance and healthspan.

The catch is that heat training can be brutally taxing and—if you’re careless—can backfire by cratering recovery, sleep, and training progress. Running with layers or working out in the middle of the day can truly be miserable (take it from a Texan who trained for a marathon all summer).

That’s where passive heat acclimation gets interesting. Instead of trying to “earn” heat stress by suffering through overheated training sessions, the idea is that one can apply heat after their normal workout (or on its own) via a hot bath or sauna and let physiology do the heavy lifting.

Conceptually, it’s a cousin of the “live high, train low” philosophy of altitude training: keep the quality of training intact (by working out at sea level) but add an environmental stimulus that nudges the body toward adaptations that support better oxygen delivery (by sleeping and living at high altitude).

Does passive heat training actually deliver? Or is more fitness without extra training too good to be true?

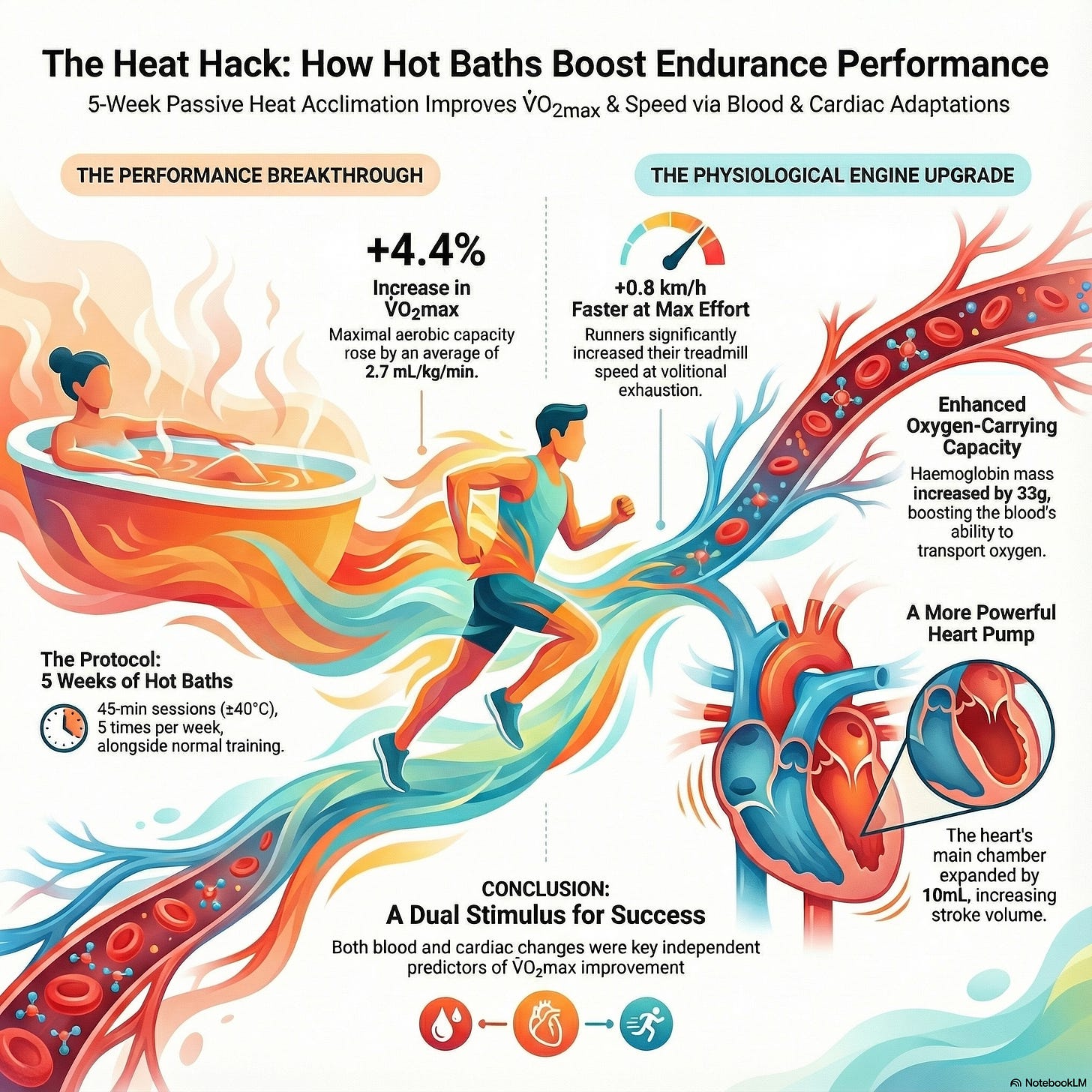

A new paper in The Journal of Physiology tested this idea by asking whether long-term passive heat acclimation, achieved through hot-water immersion, can increase VO₂max and even improve performance. And if it does, how is it working?1

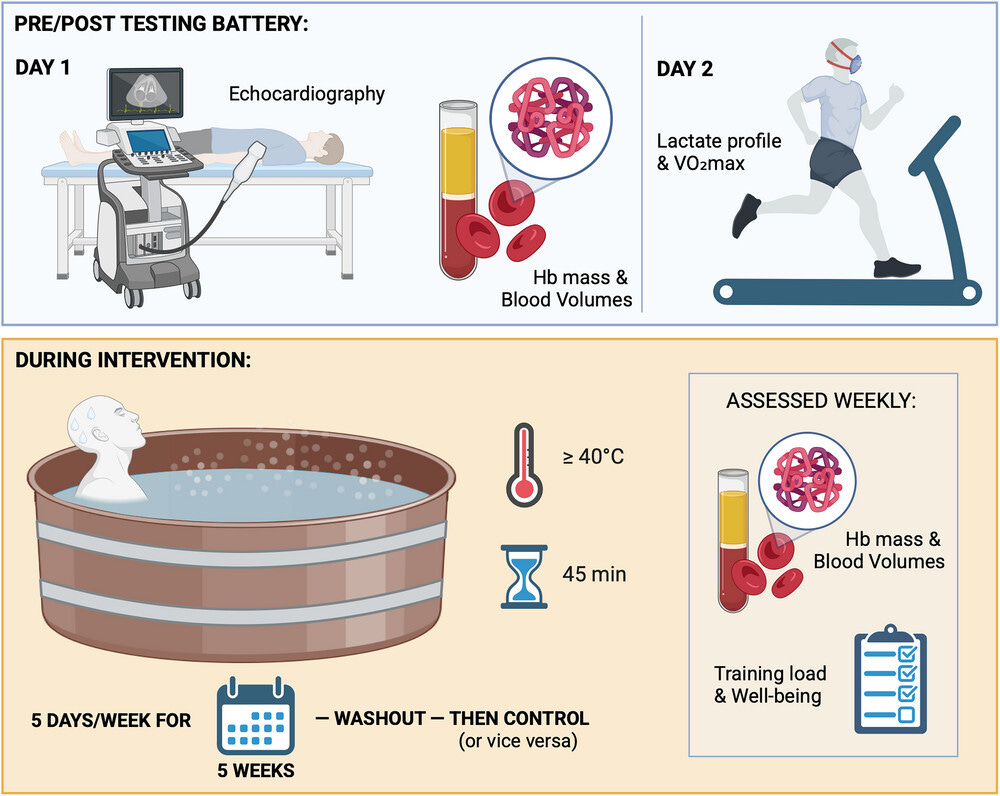

Ten endurance-trained runners (9 men, 1 woman; average VO₂max ~65 mL/kg/min—so very fit) completed two 5-week blocks in a counterbalanced crossover design (that simply means that all runners did both of the training blocks):

Hot-water immersion: 5 days per week, 45 minutes per session, starting at 104℉/40°C and gradually progressing to ~107℉/42°C by week 5. Most did the baths right after their normal run.

Control: same training as usual, no heat exposure

Crucially, the runners’ training volume, intensity (time in heart rate zones), and daily well-being (fatigue, soreness, mood, sleep, stress) were the same between conditions. So any changes are very likely coming from the heat, not extra training. This also indicates that the added heat stress didn’t compromise training quality—that’s a huge finding in my opinion.

Before and after each 5-week block, researchers measured dozens of blood markers, the runners’ heart structure and function, and even performance via a treadmill VO₂max, running economy, and lactate threshold test.

Altitude-like adaptations after hot bathing

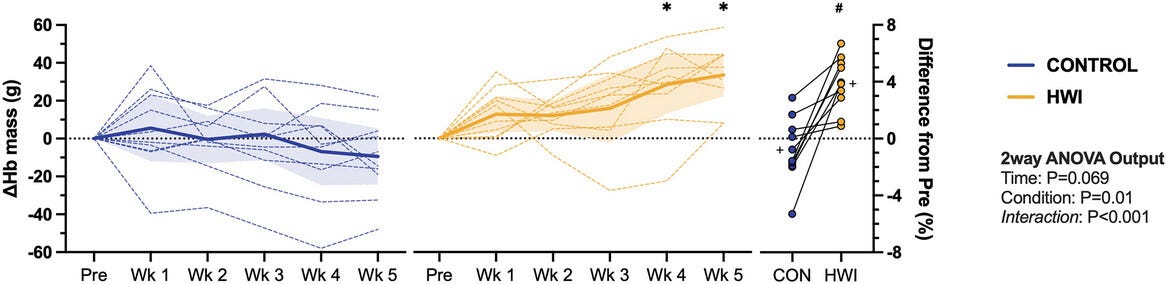

After 5 weeks of hot water immersion, hemoglobin mass (hemoglobin is the oxygen-carrying protein in our blood) increased by nearly 4%. The runners also had a higher total blood volume and more red blood cells after the training intervention.

But these changes didn’t happen all at once. They followed a very specific (and physiologically compatible) time course. Weeks 1–2 were characterized by a big jump in plasma volume that made the blood thinner (hematocrit, the percent of red blood cells that make up your total blood volume, declined by nearly 2%). During weeks 4–5, plasma volume started to drift toward pre-training values, while red blood cell volume and hemoglobin levels started to rise.

That staggered response fits the something the authors call the “kidney critmeter” idea: first, you expand plasma, which lowers hematocrit and oxygen content (the “diluting” effect observed in weeks 1–2); the kidneys sense that and turn up EPO (erythropoietin) and red blood cell production to restore an optimal hematocrit. You end up with more total blood and more hemoglobin on board without permanently thinning or thickening the blood.

Interestingly, hemoglobin concentration didn’t really change during the study, because both plasma and red cells increased. As we’ll see, this led to some notable changes in the runners’ oxygen-carrying capacity.

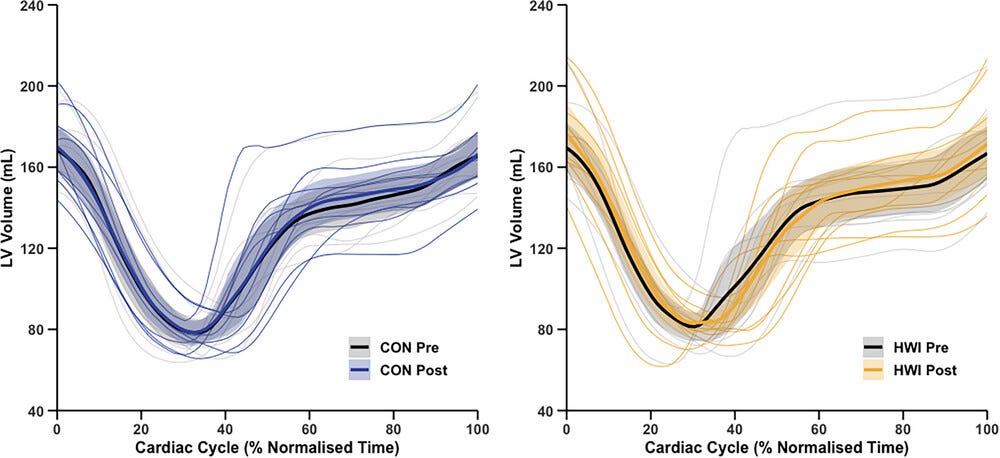

What changed in the heart?

The runners’ hearts were able to store more blood in the “relaxed” state (known as diastole), as shown by an increase in their left-ventricular end-diastolic volume or LVEDV, which rose by 10 mL after the hot water immersion condition but didn’t change after the control condition (even with training). The runner’s stroke volume—how much blood their hearts could pump with each beat—increased by 7 mL, and their resting cardiac output rose by 0.6 liters per minute.

On the other hand, the mass of their left ventricle (the main pumping chamber of the heart) or other measures of heart function (e.g., end systolic volume or left ventricular mass) didn’t change much. So we’re not seeing a thicker, more muscular heart, but rather, more of a bigger, better-filled reservoir. With more blood volume returning to the heart, it stretches more, fills more, and pumps more per beat (via the Frank-Starling mechanism).

The authors even estimate that, if the stroke-volume increase at rest carries over to maximal exercise, the heart could deliver ~200 mL or more oxygen per minute at maximal effort—enough to explain the VO₂max gains they observed!

Did heat training actually move performance?

It did, but in a very specific way.

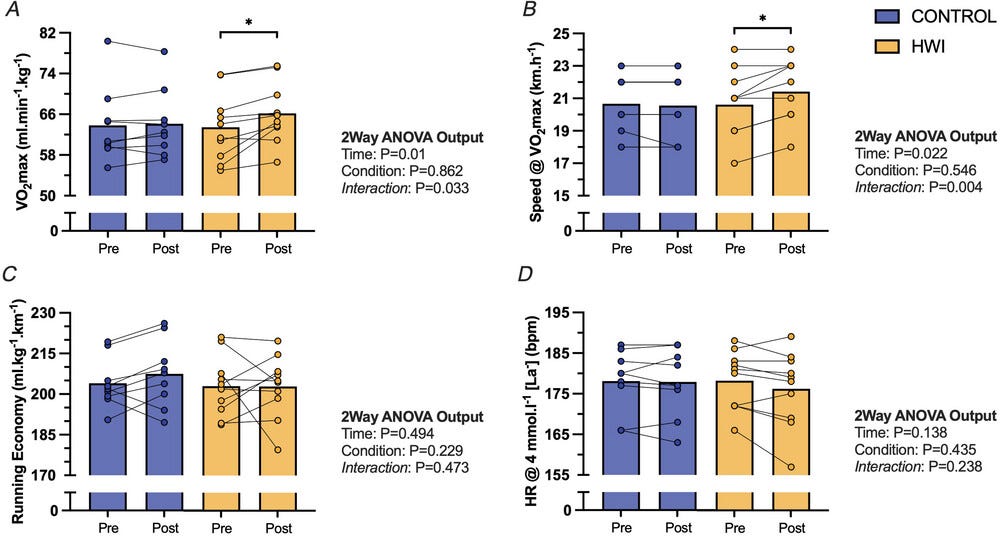

The runners’ relative VO₂max increased by 2.7 mL/kg/min (about ~4.4%). That’s the kind of VO₂max bump you might hope for from a well-designed altitude camp, and it happened with zero added mileage and no change in workout intensity.

The runners also improved their running speed at VO₂max by 0.5 mph or 0.8 km/h. Simply put, they could run at a faster “all-out” speed after the 5 weeks than they could before.

But here’s the nuance: running economy didn’t change, nor did speed or heart rate at lactate threshold—two crucially important pieces of running performance! The heat didn’t make these runners more economical or shift their threshold, but it did raise their ceiling.

The authors also ran an analysis to see which variables “explain” VO₂max changes best, and two stood out: hemoglobin mass and heart function. Each 1 g increase in hemoglobin mass was associated with a 3.8 mL/min increase in VO₂max, while each 1 mL increase in LVEDV was worth 11.7 mL/min of VO₂max.

Together, these two explained about 82% of the variance in VO₂max across all measurements. In their words, the VO₂max gains after hot water immersion can be “largely explained” by simultaneous adaptations in blood and heart volume. Passive heat training seems to act on both sides of the determinants of VO₂max: more oxygen in the blood and a bigger pump to deliver it.

If you zoom out, the reason this study is exciting has less to do with any single sport and more to do with the underlying target: raising your aerobic ceiling.

VO₂max isn’t just a “performance metric.” It’s a proxy for your ability to deliver and use oxygen—tightly tied to cardiac output, blood volume, and mitochondrial capacity. In the real world, higher aerobic fitness tends to translate into a bigger buffer for daily life. Climbing stairs, carrying groceries, playing with your kids, tolerating stress, bouncing back faster, and yes, performing better in whatever training you care about. It’s also one of the strongest predictors of healthspan and longevity.'

In fact, the change in VO₂max observed among the runners in the study (2.7 ml/kg/min or about 4%) is also clinically meaningful. A ~3.5 ml/kg/min increase in aerobic capacity is associated with a 13% lower risk of all-cause mortality and a 15% lower risk of cardiovascular disease in meta-analyses.2 (Is this why we see lower rates of CVD and other chronic diseases among long-term and frequent sauna users? Perhaps).

This paper suggests something pretty specific (and pretty rare among health or performance interventions)—a meaningful VO₂max bump without adding training volume or intensity. That’s something no supplement or biohacker therapy can come close to achieving.

Mechanistically, hot baths (and sauna) are compelling because they target two major bottlenecks that matter for VO₂max and long-term cardiovascular resilience:

More oxygen-carrying capacity (hemoglobin mass/blood volume changes)

A heart that fills and pumps more per beat (bigger “reservoir,” higher stroke volume)

The fact that a passive heat stress was able to not only improve aerobic fitness and performance in well-trained runners, but also improve their heart’s structure and function, is somewhat remarkable. Elite-level training generally leaves little room for the heart to adapt (it’s pretty optimized).

I think it shows how powerful heat is as a novel stimulus.

How to use this (without making your life miserable)

Now for the disclaimers.

All of us should be thinking of passive heat as a “multiplier,” not a replacement. You still need the foundation (regular aerobic work and some intensity over time). Heat is an add-on that may help elevate the ceiling.

Based on this study, a realistic starting template is 4–5 sessions/week of hot-water immersion, ~30–45 minutes, ~104–107℉ (40–42°C), often done after training.

But scale it like an adult. The study protocol is legitimately hard. And heat is a real physiological stressor. Start with a lower temperature, shorter duration, or fewer sessions per week, and build tolerance gradually. No need for hero sessions. And this should go without saying: be safe and take your personal medical issues into consideration (if applicable).

Where do I see heat training fitting into your regimen? Use it strategically when training load is already high. If you’re strength training hard, ramping conditioning, or managing joint/tendon limits with running mileage, passive heat may be one way to add cardiovascular stimulus without more impact.

Finally, let’s remember the boundary of the evidence here. This is a 10-person study, mostly male, for 5 weeks, in highly trained runners. We don’t yet know how well it generalizes to other populations, other heat modalities (like sauna), or longer time horizons. My hunch, though, is that people with more “adaptation runway” may respond at least as well… but that remains a hypothesis.

Sometimes (okay, most of the time) the simplest path to a higher VO₂max is still the boring one—train consistently, progress gradually, and recover well.

However, if you’re already doing that, and you want a tool that may help elevate your aerobic ceiling without extra pounding, getting hot (passively) is an intriguingly data-backed option.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 30% off their order this week. So stock up!

ProBio Nutrition—the all-in-one supplement that I use every single day—is offering 20% off. My preference is the tangy orange flavor, but they also sell an unflavored “smoothie booster” that’s great in a shake, smoothie, or juice.

Equip Foods makes some of the cleanest, best-tasting protein products around. I am absolutely obsessed with their Prime grass-fed protein bars (the peanut butter ones are to die for). Take up to 10% off site-wide!

Consensus is the AI-powered research engine that I use daily to stay up to date on the literature and make sure I’m covering the latest and most rigorous science. They’re giving my audience 1 month of premium for free.

Really enjoyed this breakdown and I love the “altitude in disguise” framing!

From a clinician’s lens, the most interesting part is that the adaptation seems to be systems-level (blood volume/hemoglobin mass + cardiac filling/stroke volume), not just “feeling tougher in the heat.” That’s exactly why VO₂max is such a powerful health marker: it reflects oxygen delivery capacity and physiologic reserve, not a single organ or lab value.

I also appreciate the nuance you highlighted: the intervention raised the ceiling (VO₂max / vVO₂max) without obviously shifting economy or threshold, which suggests passive heat may be a smart “multiplier” for the right person rather than a replacement for training.

Practical point for readers: heat is a real stressor. Starting conservatively (shorter, cooler, fewer sessions) and respecting contraindications (syncopal history, unstable cardiac disease, dehydration, pregnancy, etc.) matters as much as the protocol.

Curious if you’ve seen comparable effects with sauna vs hot-water immersion in the literature!

nobody talks about HOT baths!!!! love this!