Physiology Friday #298: Does Being Fit Make Alcohol Harmless?

Or—can you outrun a few drinks?

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter and deals on products, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, Equip Foods, Consensus, and ProBio Nutrition can be found at the end of the post.

No single health topic is as divisive as alcohol.

Some argue it’s a “literal poison” and should never be consumed. Others argue that otherwise healthy people can consume alcohol in moderation without worrying too much.

The problem is that both sides come armed with data. One can easily find studies supporting the “unhealthy at any dose” argument or the “moderate drinking is okay” point of view.

Why’s it so equivocal? Because all of the alcohol research comes from observational data—that is, everything we know is drawn from studies that associate health outcomes with self-reported alcohol consumption over a specified period of time. That is hardly the most robust way to answer a question as important and controversial as whether alcohol is safe in moderation. But it’s all we have for now.

The main problem with observational research is that, while it can answer some questions on a population level (“how many drinks is safe?”), it doesn’t really do much to inform personal health decisions based on one’s unique circumstances or lifestyle habits. And those unique circumstances and lifestyle habits matter because they almost certainly influence how alcohol affects one’s long-term health.

Some factors (e.g., being overweight, genetic predispositions, or comorbid conditions) make alcohol’s damage worse, while others (e.g., healthy diet, exercise, and sleep habits) may buffer alcohol’s health effects.

That brings us to a key question on a lot of minds: Is it okay for someone who works out regularly, maintains a healthy body composition, eats right, and otherwise has no health issues to drink alcohol occasionally if they choose to?

Most would say yes—in moderation, it probably doesn’t pose a huge risk. However, there’s not a lot of evidence to back up this statement.

Lucky for us, a new large-scale analysis out of Norway asked a similar question, but instead of asking “Do drinkers die earlier?” or “Are fit people protected?” from a single snapshot in time, the researchers asked a more realistic one: what happens when people’s drinking and fitness change over ~10 years?1

The answer may not be what you expect—it suggests that fitness is a much more powerful lever for health than alcohol.

Researchers used two waves of the large Norwegian population cohort known as the HUNT study (HUNT2 in 1995–97 and HUNT3 in 2006–08). They excluded people with prior major cardiovascular disease and cancer and ended up with 24,853 “healthy” adults (about 54% women; average age ~55). The follow-up (when deaths were monitored) started at HUNT3 and ran through mid-June 2024, giving a median follow-up period of just under 17 years.

Alcohol exposure (change over ~10 years) was based on self-reported intake and categorized at each time point as:

Abstainer

Within recommendations (≤140 g/week for men and ≤70 g/week for women; about 10 and 5 drinks per week, respectively).

Above recommendations (>140 g/week for men and >70 g/week for women).

This information was then used to create “change categories.” For example, people who went from being abstainers to drinking within/above the recommendations, drinkers who reduced their alcohol consumption (going from above to within/abstention), or those who maintained their abstention or alcohol consumption habits during the 10-year follow-up.

Fitness exposure over 10 years wasn’t defined in the traditional sense using cardiorespiratory fitness—it was estimated from a validated non-exercise equation using age, sex, waist circumference, resting heart rate, and physical activity levels. Participants were classified as:

Unfit: bottom 20% for age and sex

Fit: top 80% for age and sex

This created four fitness-change groups (fit→fit, fit→unfit, unfit→fit, unfit→unfit).

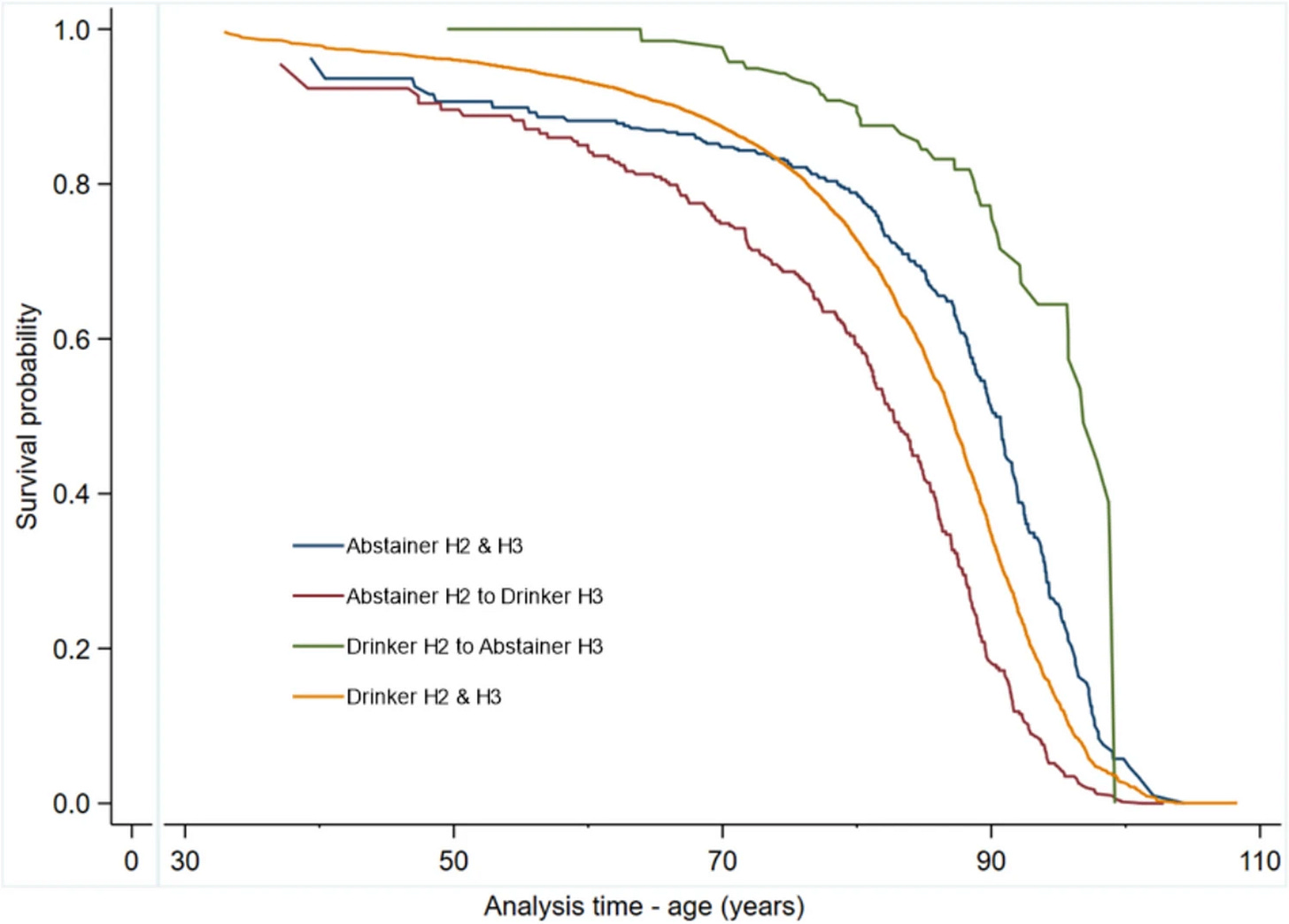

Drinking changes were associated with higher mortality, but the pattern matters

In the main alcohol-change results, the reference group is people who were abstainers at both HUNT2 and HUNT3. Here’s what happened relative to that reference (simplified into bullet points. You’re welcome):

Abstainer → within recommendations: 20% higher mortality risk

Within recommendations → abstainer: 16% higher risk

Within → within (stayed within recommendations): 6% higher risk

Within → above recommendations: 24% higher risk

Above → within recommendations: 42% higher risk

Above → above (stayed above): 20% higher risk

A nuance the authors emphasize is that on paper, it looks paradoxical that reducing drinking from above to within recommendations or even from within to abstaining still carried a fairly large excess risk (16–42%). That’s a classic signal that “change” can reflect underlying health trajectories (people sometimes cut back because of emerging illness) and that alcohol categories can be confounded by who ends up in them over time. It’s a bias that shows up a lot in alcohol-related research.

What this alcohol-only analysis shows (and tends to reinforce) is that there doesn’t appear to be any “safe” level of alcohol consumption on a population-wide basis. All categories of drinking carried a higher risk than the long-term abstainers. However, I will note that the hazard ratios for nearly all of the categories (hazard ratios being the statistic used to express the risk of mortality in one group vs. another) had confidence intervals that contained 1.0—meaning that statistically speaking, drinking did not carry a higher risk after adjusting for several known confounders.

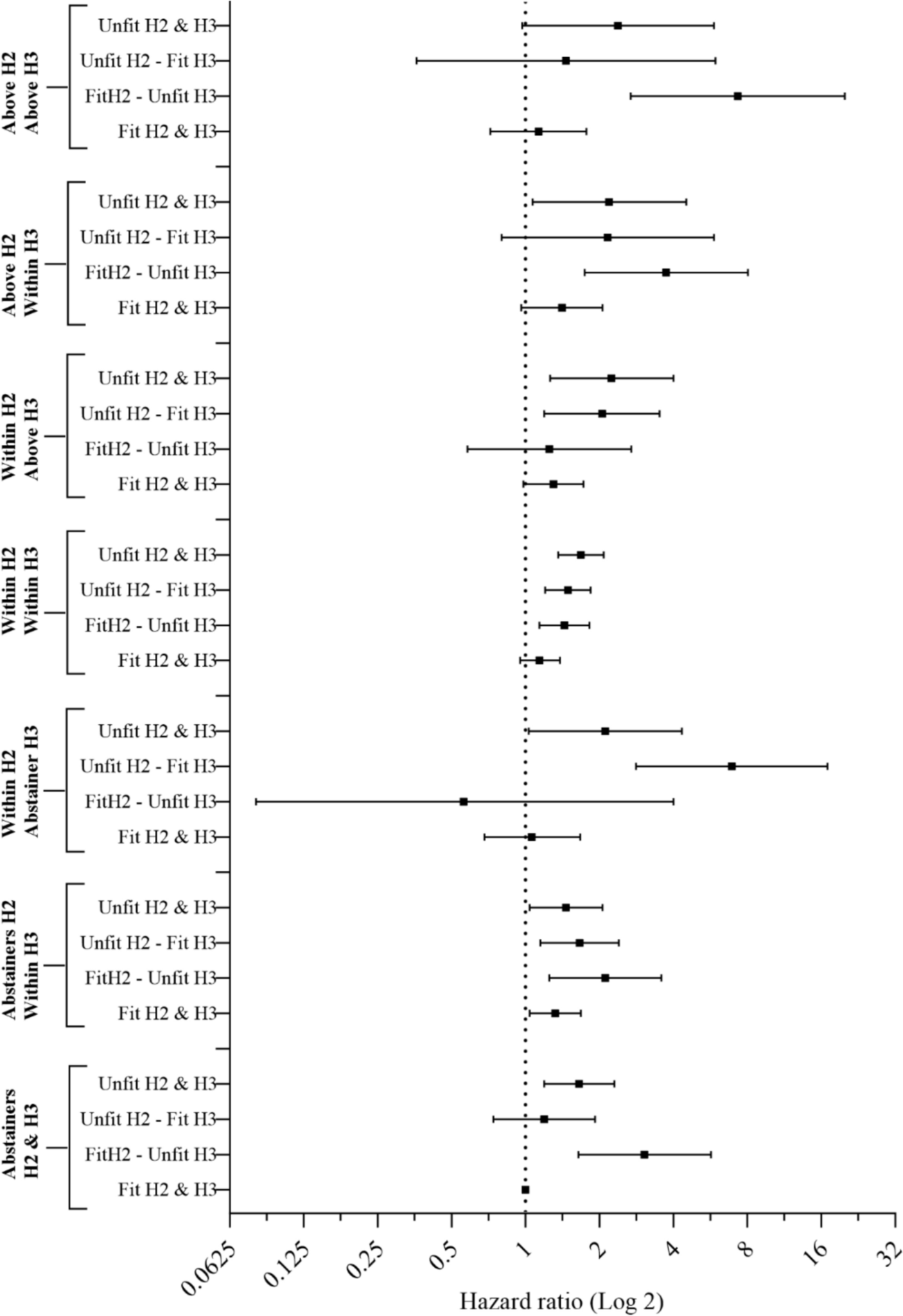

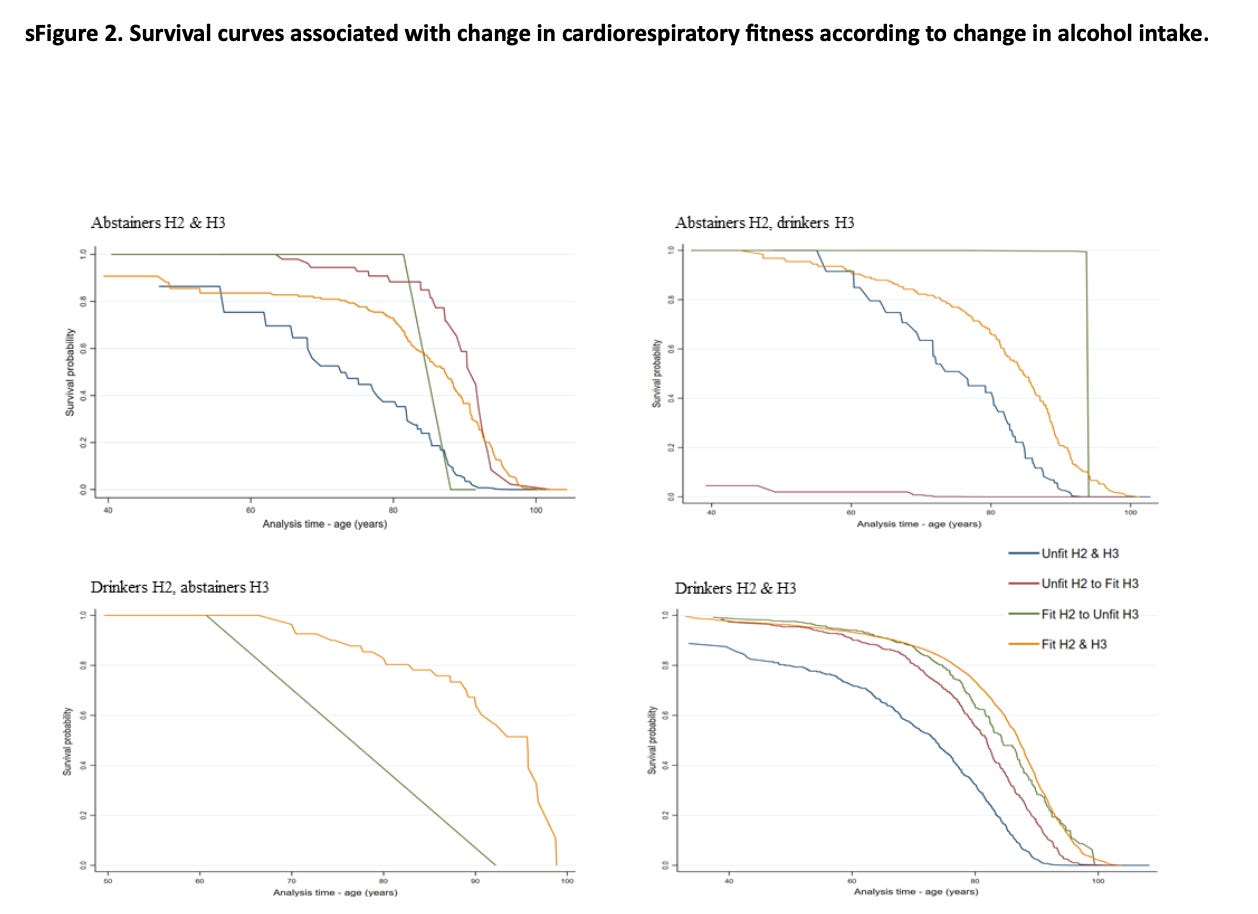

Fitness changes were the bigger lever

Here’s where the paper earns its headline. Changes in cardiorespiratory fitness modified the alcohol–mortality association, and staying out of the lowest-fitness bucket was more predictive than alcohol change categories alone.

Here, the reference group shifts to a very specific and important comparator: abstainers who remained fit from HUNT2 to HUNT3 (in other words, long-term fitness maintainers).

Relative to that “fit-abstainer” reference, the standout theme is that if you remained unfit (in the bottom 20%), mortality risk was elevated across nearly all of the alcohol change patterns. For example:

Remaining unfit + remaining abstinent: 65% higher risk

Remaining unfit + abstainer → within recommendations (“started drinking”): 46% higher risk

Remaining unfit + within → abstainer (“stopped drinking”): 111% higher risk

Remaining unfit + within → within (“consistent within-limit drinking”): 68% higher risk

The penalty attached to being persistently unfit is large enough that it shows up even among abstainers, and it remains visible regardless of whether drinking status improves or worsens.

Now flip it around: If you remained fit, the mortality risk associated with alcohol change was generally not higher than the reference (i.e., alcohol did not increase mortality risk), except for one consistent finding—those who started to drink (abstainer → within recommendations) still showed a 32% higher risk compared with abstainers who stayed fit. But otherwise, people in the top 80% of fitness had a mortality risk on par with fit abstainers, regardless of whether they consumed alcohol within or above the recommendations or whether they increased, decreased, or maintained their alcohol habits over 10 years.

Losing fitness is especially costly

The paper also reports results framed as “within-alcohol-group” comparisons, which helps clarify the cost of declining fitness.

Among persistent abstainers, transitioning from fit → unfit carried a hazard ratio of 3.05 versus peers who remained fit. That’s a 205% higher risk.

Among consistent drinkers, transitioning from fit → unfit carried a hazard ratio of 1.48 versus peers who remained fit—a 48% higher risk.

They also report a somewhat counterintuitive finding: even people who improved their fitness (unfit → fit) could show elevated risk in certain alcohol-change categories (e.g., abstainer → drinker or consistent drinkers), which likely reflects the reality that being unfit at baseline can be a marker of prior risk, illness, or unfavorable physiology that isn’t fully erased by gaining fitness later. Only persistent fitness maintenance over time provided “protection” against alcohol.

This study reframes the “mitigation” question I asked at the beginning of this newsletter in a more useful way. Instead of asking whether you can offset alcohol with training, the more actionable question is whether or not you’re protecting your fitness floor over the years.

In this dataset, staying out of the bottom fitness bracket was associated with a markedly more favorable risk profile across nearly all drinking categories. That points to a training priority: preserve fitness through consistency, avoid long periods of deconditioning. Never transition to “unfit.”

Alcohol still matters, and I don’t want to gloss over the fact that consuming it can pose real health risks. But the clearest signal here is that eroding fitness (or never being fit in the first place) is more hazardous than a “within limits” approach to alcohol.

That might seem surprising to some, but for others, it’s vindication—alcohol probably isn’t great, but it’s perhaps not the boogeyman that the wellness space has made it out to be. In the context of a healthy lifestyle, social drinking may not pose a major long-term health risk (though your mileage may vary).

What I find most remarkable about these results is that we still see a fitness > alcohol signal even when defining fitness and alcohol consumption using very loose categories! Imagine if the authors had used more granular fitness categories (the top 10% or 20%, for example) or a more robust measure of fitness, such as VO2 max, strength, or some combination of these plus metabolic risk factors. The drinking categories were also broad and only captured two patterns among drinkers: those who drank 5–10 drinks per week or less, and those who drank more than that. This fails to isolate the “social drinkers” (like me) who might have 1–2 drinks per week at most.

Had we honed in on these more specific fitness and alcohol consumption patterns, I speculate that we’d see an even stronger risk mitigation result among the fit drinkers. In fact, I’d wager that an extremely fit “social drinker” might even have a lower mortality risk than a lesser fit teetotaler.

Maybe that’s my personal bias coming through.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 30% off their order this week. So stock up!

ProBio Nutrition—the all-in-one supplement that I use every single day—is offering 20% off. My preference is the tangy orange flavor, but they also sell an unflavored “smoothie booster” that’s great in a shake, smoothie, or juice.

Equip Foods makes some of the cleanest, best-tasting protein products around. I am absolutely obsessed with their Prime grass-fed protein bars (the peanut butter ones are to die for). Take up to 10% off site-wide!

Consensus is the AI-powered research engine that I use daily to stay up to date on the literature and make sure I’m covering the latest and most rigorous science. They’re giving my audience 1 month of premium for free.

I'd like to see this analysis with a different fitness breakpoint — considering the top 80% as "fit" seems like a pretty low bar... What does this look like for the top 20%? Even so, I'll still use this to reinforce my rationalization that a post-run beer brings me more goodness than trouble.

It is hard to imagine an adult that abstains deciding to begin drinking up to 15 drinks a week.

As I often say when I see articles on alcohol, I can't imagine 15 drinks a week wouldn't interrupt my normal week. I could not have had 3 drinks and still done my treadmill work out last night as a quick example.