Physiology Friday #299: What Really Drives Low Heart Rate in Endurance Athletes?

Genetics versus training in bradycardia.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter and deals on products, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, Equip Foods, and ProBio Nutrition can be found at the end of the post.

I wear my low resting heart rate (it’s typically 32–35 beats per minute overnight) like a badge of honor. And maybe I should.

A resting heart rate in the 30s to 40s is usually celebrated as a sign of good cardiovascular fitness. Many people strive to get their resting heart rate as low as possible (within means). But can heart rate drop “too low”? And if so, what are the consequences?

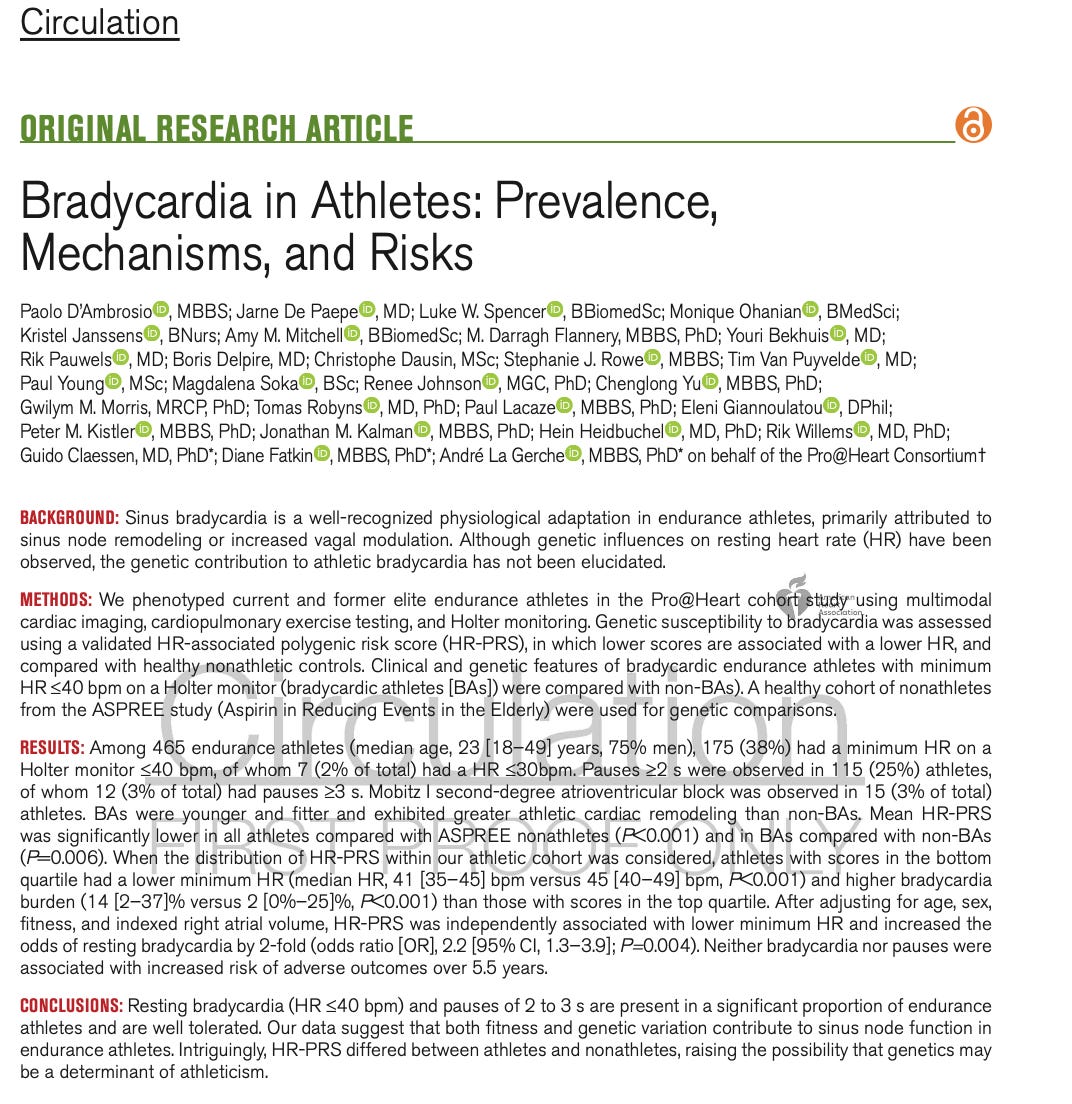

That’s the psychological (and physiological) space that a new paper in Circulation lives in: it takes a phenomenon we tend to romanticize (a very slow heart rate in highly trained people like endurance athletes) and asks three very relevant questions. How common is it when you measure it carefully? What does it correlate with inside the heart (structure, function, and rhythm patterns)? And most importantly, does it appear dangerous in the real world?1

They’re questions I certainly want to know the answer to, and maybe you do too.

But the paper has a twist that I think makes it much more interesting than “athletes have low heart rates.” The authors don’t treat low heart rates (referred to as bradycardia) as purely a training adaptation. They test whether inherited biology—genetics—meaningfully contributes to it.

(By the way, the irony of “bradycardia” is not lost on me).

Clinically, bradycardia is just a slow heart rate. In some settings, it’s benign, in others it’s a clue that something is wrong with the sinus node (the heart’s natural pacemaker) or the conduction system that carries electrical signals through the heart.

The tricky part is that endurance training can produce a version of bradycardia that is, for many people, completely normal. That’s where the tension comes from. The same label can describe both an adaptation and a pathology.

Historically, the “athlete bradycardia” explanation leaned heavily on autonomic tone—especially increased parasympathetic (vagal) influence. More recently, evidence has accumulated that the sinus node itself may remodel with long-term endurance training, shifting its intrinsic pacing. And separate from training, large population studies suggest resting heart rate is partly heritable, or determined by genetics.

This study tries to put those pieces together by measuring the phenotype deeply and asking whether genetics adds explanatory power beyond fitness, training, and heart structure.

The cohort included 465 current and former elite endurance athletes from the Pro@Heart/ProAFHeart studies. They were young overall (with a median age 23), mostly male (75%), and almost entirely of European ancestry. The sports mix was heavy on cycling (37%) and rowing (34%), with meaningful representation from running (16%) and triathlon (10%) too.

Every athlete went through a pretty comprehensive workup, including:

resting ECG.

a 24-hour Holter monitor (continuous ECG) while living and training normally.

cardiopulmonary exercise testing to quantify aerobic fitness (VO₂peak and % predicted VO₂peak).

cardiac imaging (echo plus cardiac MRI).

They defined “resting bradycardia” as a minimum heart rate ≤40 bpm, where “minimum” meant the lowest sustained heart rate averaged over at least 30 seconds. That’s a more robust definition than a single instantaneous low point, which can be an artifact, a brief ectopic beat, or a random blip. They also calculated “bradycardia burden,” the percentage of the monitoring period spent below 50 bpm. Pauses in heart rate were defined as prolongations ≥2 seconds (and they also looked at ≥2.5 and ≥3 seconds). They tracked heart block patterns too, and importantly, tracked long-term health outcomes for up to 5 years.

The genetics piece included a heart-rate polygenic risk score (HR-PRS) built from ~13,000 common variants. Lower scores correspond to a genetic tendency toward a lower heart rate. For a reference population, they used a large cohort of over 12,000 older, healthy, nonathletes without diagnosed cardiovascular disease who were genotyped using comparable methods.

Slow is common

In this cohort, 38% had a minimum HR ≤40 bpm. Only 2% reached a sustained minimum ≤30 bpm. That’s a useful anchor because “30s” is the number that tends to make people anxious, and here it’s uncommon even among elite endurance athletes.

Pauses showed up too, but again with a distribution that matters: 25% had pauses ≥2 seconds, while only 3% had pauses ≥3 seconds. Second-degree heart block appeared in 3% of the population overall, and importantly, there were no cases of complete heart block—patterns that would be much harder to dismiss as benign training-related findings.

The bradycardic athletes, as a group, weren’t just a little slower. Their median minimum heart rate was 37 bpm (vs 46 bpm in the non-bradycardic group), and they spent 33% of their day under 50 bpm. (vs 2% in the non-bradycardic group). Pauses ≥2 seconds were dramatically more common in the bradycardic group (45% vs 13%), and second-degree heart block was more frequent (6% vs 2%). At the same time, atrial fibrillation was similarly uncommon in both groups.

Bradycardia tracked with fitness and remodeling

The bradycardic athletes were, on average, younger, leaner, and fitter. Their VO₂peak was higher—60 vs 50 mL/kg/min—and their percent predicted VO₂peak was also higher (131% vs 124%). They also reported higher training volume (about 86 vs 74 MET-hours/week), and a slightly longer training history. What this tells me is that a low(er) resting heart rate is, in part, determined by training characteristics.

Bradycardia also tracked with a more expanded endurance phenotype when looking at heart imaging. They showed indices consistent with robust diastolic function, and had larger atrial volumes and substantially larger ventricular volumes. In other words: bigger pumps, same efficiency, and a lower “idle speed.”

The authors also reported moderate negative correlations between minimum heart and ventricular size. That’s a fancy way of saying what physiologists have been saying forever: if the heart can eject more blood per beat, it can maintain cardiac output with fewer beats.

Training matters, but genetics still moves the needle

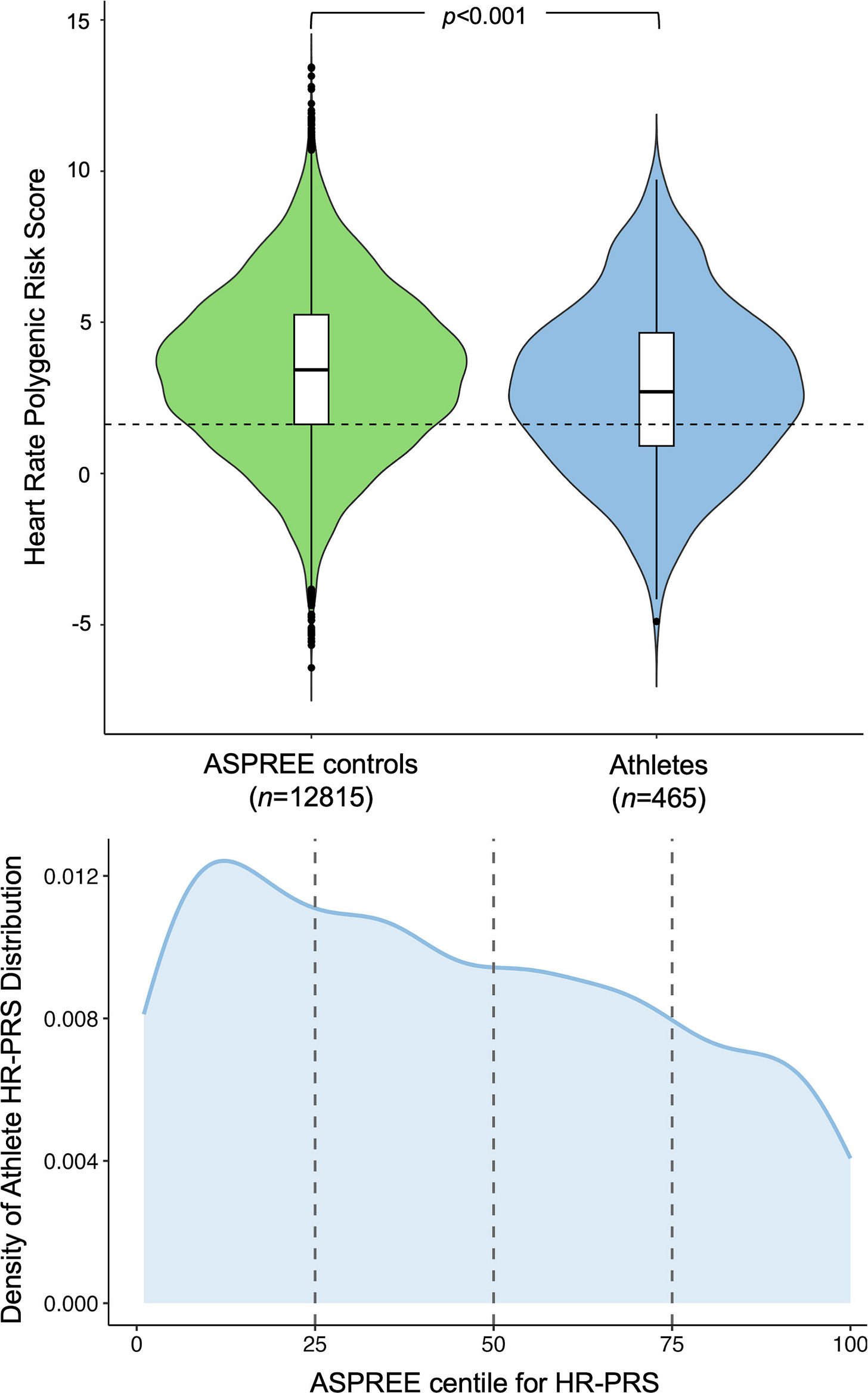

Here’s where the paper steps beyond the athletes heart and provides us with some novel info. Compared with the nonathletes, athletes had a lower heart rate polygenic risk score (HR-PRS) on average. They were also overrepresented in the “low HR-PRS” range: 34% of athletes fell into the bottom quartile of the non-athlete distribution, while only 18% landed in the top quartile (versus 25%/25% as expected by definition).

That pattern raises the possibility that people who end up thriving in endurance sport may be partly “pre-selected” by traits that make high-volume training more compatible—lower intrinsic heart rate tendencies, larger stroke volume potential, or other physiological adaptations.

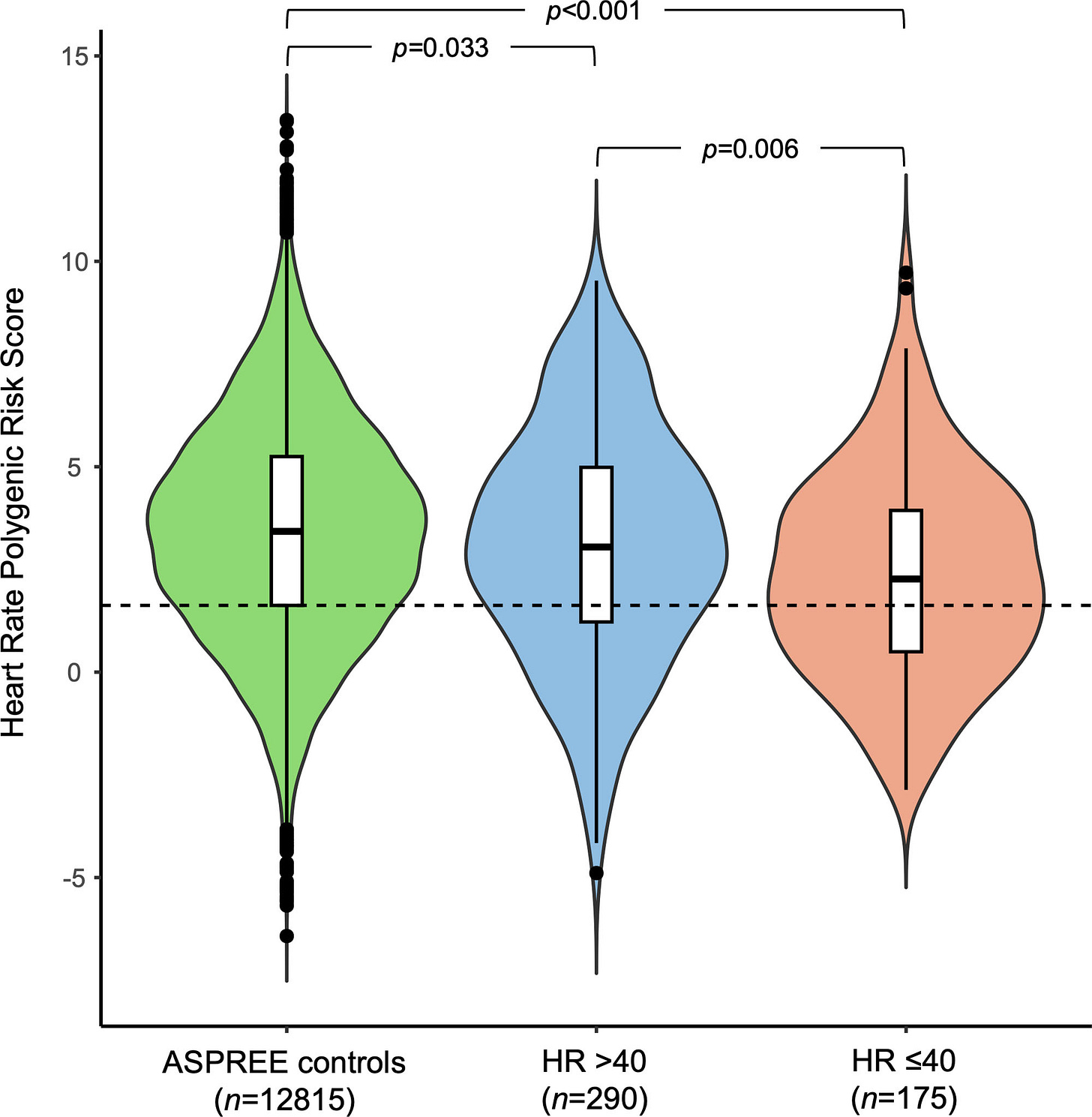

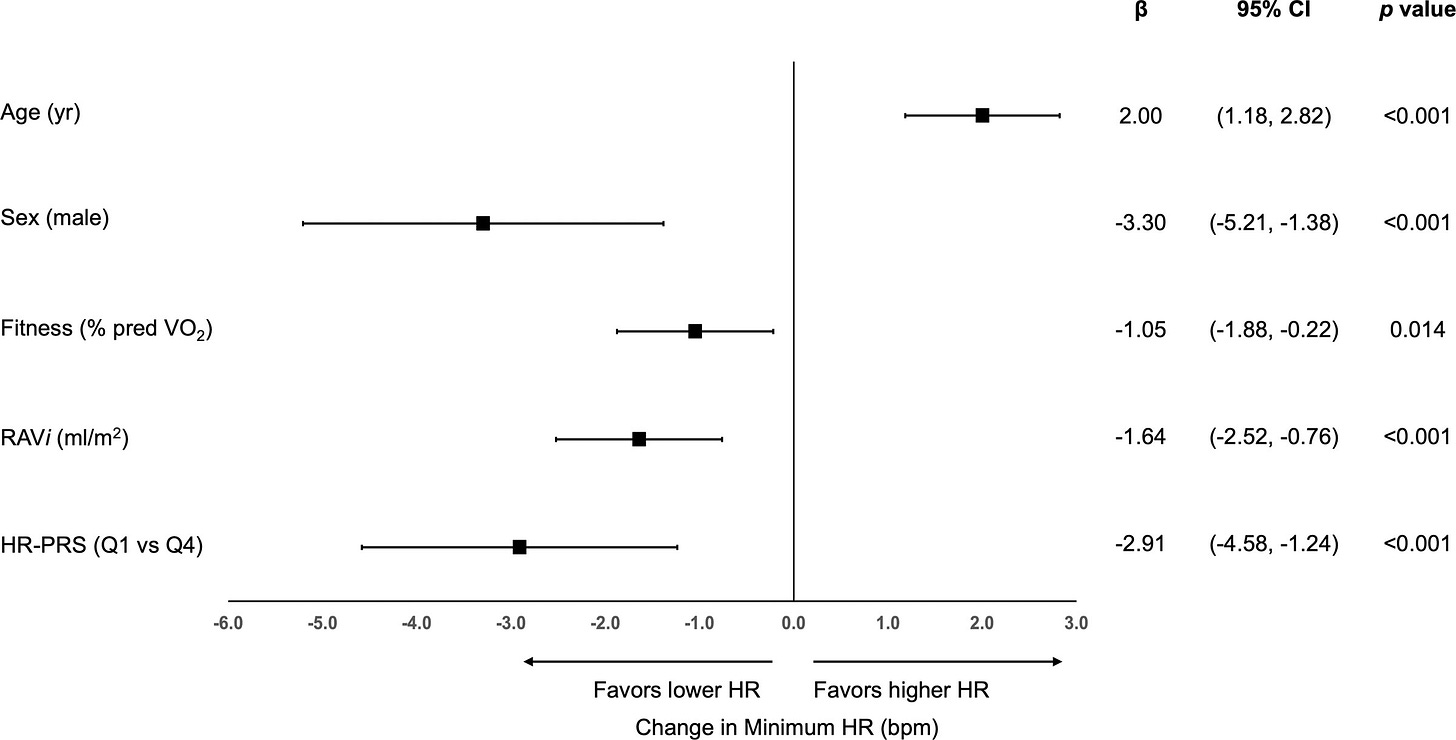

Within the athlete cohort, genetics also aligned with the bradycardia phenotype in a clean way. Athletes in the bottom HR-PRS quartile (more genetically predisposed to lower HR) had a lower minimum heart rate (41 vs 45 bpm), a higher average time spent under 50 bpm (14% vs 2%), and more pauses ≥2 seconds (36% vs 21%), despite similar training history and similar VO₂peak. They also had larger atrial and ventricular volumes, which is fascinating because it suggests the “low heart rate” genetic signature may accompany aspects of cardiac structure.

Most importantly, genetics still mattered after accounting for obvious confounders like age, sex, fitness, and right atrial size. Being in the bottom HR-PRS quartile carried about a two-fold higher odds of meeting the bradycardia definition (minimum heart rate ≤40). That doesn’t mean that genes determine your heart rate, but it does mean that even in a population where training is intense and relatively similar, inherited variation still explains meaningful differences.

Does bradycardia pose a risk?

Over a median of 5.5 years of follow-up, bradycardia and heart rate pauses were not associated with an increased rate of adverse outcomes. Seven athletes reported syncope (fainting); one athlete had a concerning episode during a race, and a permanent pacemaker was implanted in one older former athlete (76 years old). Twelve athletes developed newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation (3 in the bradycardic group, 9 in the non-bradycardic group). And notably, among the seven athletes with a minimum heart rate ≤30 bpm, none had syncope, pacemaker implantation, or other major adverse outcomes during the follow-up window.

That’s the reassuring finding. In young, high-performance endurance athletes, slow heart rates and even 2–3 second pauses—especially at night—appear to be well tolerated in the medium term.

The caveat here is obvious but important: 5–6 years is not a lifetime. This study doesn’t answer whether decades of extreme endurance training combined with certain genetic profiles might increase the long-term likelihood of clinically meaningful heart disease or dysfunction later in life. It does quell some anxiety (mine included) in the short and medium term, but it’s not a blanket guarantee across aging.

Where I land

I think the most valuable contribution here isn’t the prevalence numbers (though they’re helpful). It’s the framing shift. Bradycardia in highly trained people seems to be a natural trait. Fitness and cardiac remodeling matter, but genetic predisposition adds a real layer, and it may even influence who becomes an “endurance athlete” in the first place.

Practically, it also nudges us toward a better rule of thumb for interpreting low heart rate data from wearables. The number itself is rarely the headline and maybe shouldn’t even be the goal (especially if genetics are highly involved). The headline is context—symptoms, conduction patterns, and whether the low rate is new or longstanding.

This paper supports the idea that, in otherwise healthy, well-trained individuals, a low sleeping heart rate and occasional brief nocturnal pauses can fall well within a normal physiological spectrum. The signal to take seriously is not the heart rate reading per se—it’s whether that low heart rate is accompanied by fainting, exercise intolerance, or other symptoms. Something abnormal that training can’t fully explain.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 30% off their order this week. So stock up!

ProBio Nutrition—the all-in-one supplement that I use every single day—is offering 20% off. My preference is the tangy orange flavor, but they also sell an unflavored “smoothie booster” that’s great in a shake, smoothie, or juice.

Equip Foods makes some of the cleanest, best-tasting protein products around. I am absolutely obsessed with their Prime grass-fed protein bars (the peanut butter ones are to die for). Take up to 10% off site-wide!

My Garmin seems to take an average over some amount of time to give me a number but also displays the lowest number in the last 4 hours which could be lower.

No amount of training will make us all equal. With a big enough sample size (participants) I'm sure we would find some are better suited to different sports. The champion shot putter likely couldn't train themselves into a champion marathoner and likewise the champion marathoner couldn't train themselves into a champion in shotput. With exceptions this should make larger populations better at finding those outliers.

I wonder how much selection within athletes is a problem here. They excluded basically those with existing heart problems. However, in the context of elite-athletes as compared to the "normal" population, I would expect that those who do develop issues with bradicardia/have some additional factors that make the response to bradicardia worse would quickly be sorted out of the elite (having to end their career prematurely).