Physiology Friday #300: Endurance Training Interferes with Muscle Strength Gains, But Not Hypertrophy

The "interference effect" is context-dependent.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter and deals on products, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, Equip Foods, and ProBio Nutrition can be found at the end of the post.

Earlier this week, prominent podcaster and scientist Andrew Huberman tagged me in a post asking for my take on a question that comes up constantly—both in research and in the real world:

Can you get strong and fast at the same time? Or are strength and endurance goals fundamentally at odds?

My answer: not inherently.

If someone wants to maximize aerobic fitness, they’ll typically spend more time and energy doing endurance training—often at the expense of resistance training volume, recovery, or focus. And if someone’s main goal is to get as big and strong as possible, they’ll usually devote more time to lifting, which can mean less time for endurance work. In other words, a lot of the so-called “interference” is simply a budgeting problem: limited time, limited recovery capacity, and limited room for high-quality training in both domains at once.

But there’s also a deeper idea that’s been debated for decades—that strength and endurance training might interfere at the molecular level, because the cell seems to receive two competing messages.

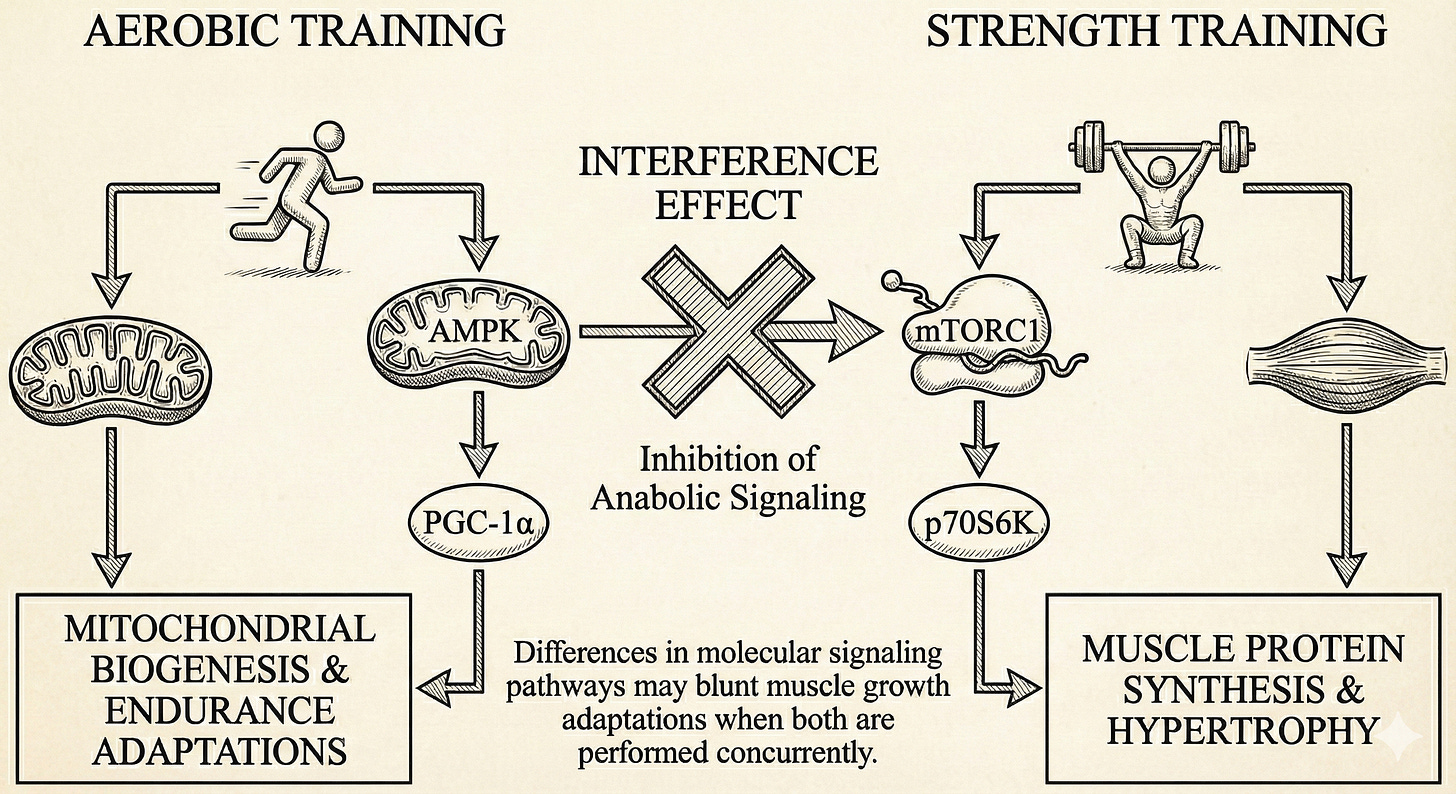

Resistance training is classically associated with mechanical tension–driven anabolic signaling that converges on mTORC1, a major regulator of protein translation and muscle growth. Enhanced signaling through mTORC1 (driven by myriad other signaling pathways that are beyond the scope of this post) supports myofibrillar protein synthesis and—over time—hypertrophy (increases in muscle size). Strength, of course, isn’t purely molecular (neural adaptations matter a lot), but mechanistically, resistance training is often framed as pushing the muscle toward contractile remodeling and protein accretion. It’s anabolic.

Endurance training, on the other hand—especially higher-intensity interval work—is more often framed around energy stress and calcium flux, increasing PGC-1α, mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative capacity, and substrate handling.

The classic interference model argues that endurance-associated signaling can dampen anabolic signaling, prioritizing energy homeostasis and mitochondrial remodeling over the energetically expensive process of building new contractile protein (and hence, muscle).

That “tug-of-war” has been used for years to explain why concurrent training might blunt hypertrophy, along with the idea that neuromuscular factors and a lower training quality (an indirect result of adding endurance training to strength work) may also constrain gains in strength and power. If so, it’s a potential reason to be more cautious about concurrent training.

The essence of this issue is this: does concurrent training actually impair the molecular and cellular processes associated with muscle hypertrophy, or is the interference effect better explained by changes in performance-level adaptations like strength?

That’s exactly the distinction the study I want to break down this week set out to test.1

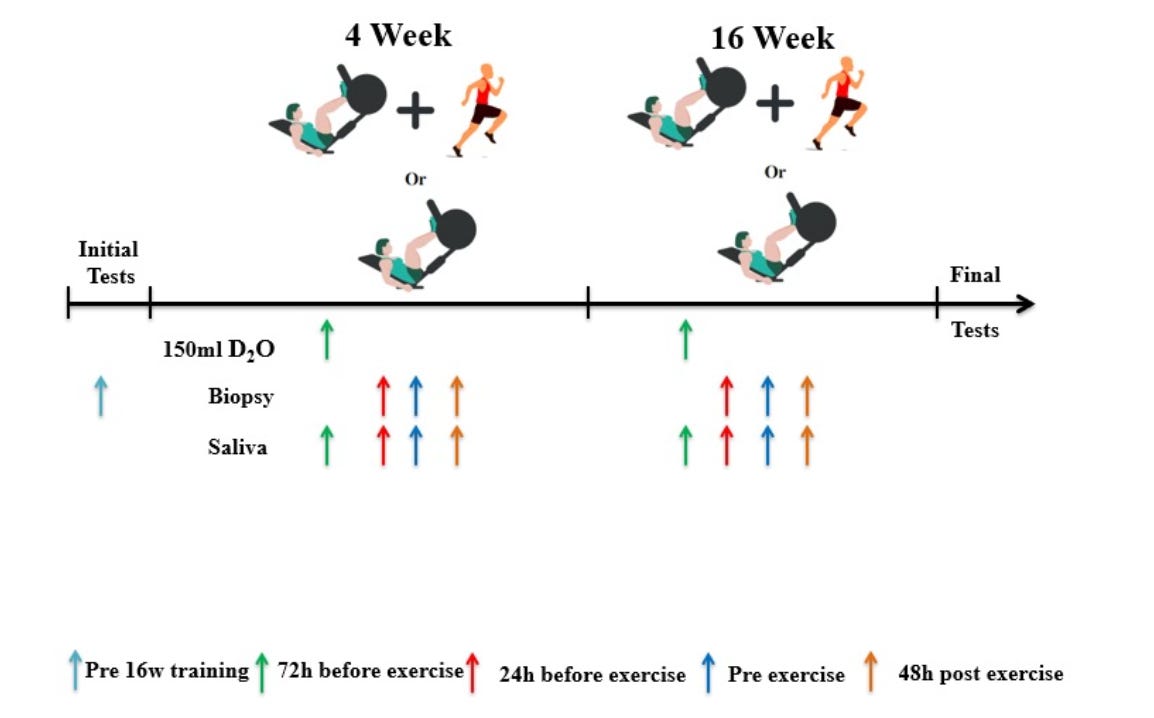

A total of 19 previously untrained young men completed the full study—10 in a resistance training-only group and 9 in a concurrent training group who performed both resistance training and weekly HIIT.

Both groups performed progressive lower-body training comprising leg press and leg extension exercise (2 sets per exercise progressing to 3 sets by the end of the study; 9–12 repetitions per set with 60 seconds rest).

On top of the same resistance program, the concurrent training group performed four weekly aerobic exercise sessions, structured as long-interval HIIT tied to their VO₂peak velocity (essentially, their maximal running speed).

Two days per week, they did resistance training followed immediately by HIIT. On two other days, they just performed HIIT (i.e., 4 total HIIT sessions per week). Intervals progressed from 10 x 1-minute efforts to 15 x 1-minute efforts to 10 x 2-minute efforts later in the study.

This was a meaningful aerobic stimulus, including sessions performed right after lifting. That’s an important distinction.

After every training session, participants consumed 30 g of whey protein to maximally stimulate muscle protein synthesis (MPS). The researchers assessed muscle strength (1 rep max), aerobic capacity (VO₂peak), type I and type II muscle fiber size (cross-sectional area), and myofibrillar protein synthesis. They also measured muscle satellite cell content, myonuclear number, and gene expression of myogenic regulatory factors—all of which are part of the core molecular machinery that governs increases in muscle size and strength in response to training.

Concurrent training compromises strength, but not hypertrophy

As expected, endurance adaptations showed up only in the concurrent training group, who increased their peak aerobic capacity by 11% (compared to no meaningful improvement with resistance training-only).

This confirms that the endurance stimulus “worked,” which is important when interpreting downstream tradeoffs.

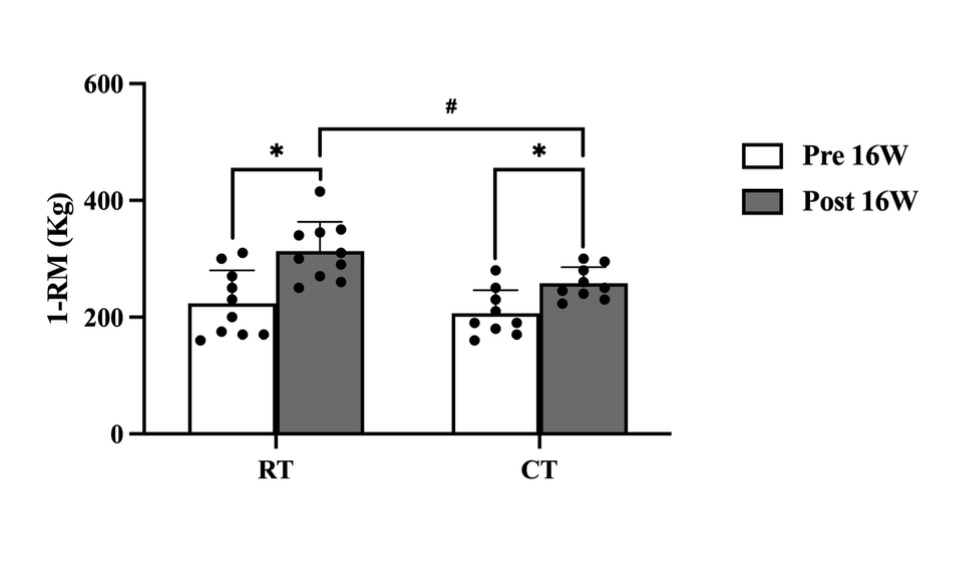

Both groups got substantially stronger over 16 weeks, but strength gains were clearly attenuated in the concurrent group.

Resistance training-only: +194 lb/88 kg improvement in leg press 1-RM

Concurrent training: +121 lb/55 kg improvement in leg press 1-RM

In percentage terms, the resistance training group saw a ~38% increase while the concurrent group saw a ~23% improvement over the course of the study. These are massive changes… but remember, these were untrained young men. Lots of room to improve.

So the classic interference effect did show up here—but specifically for maximal strength.

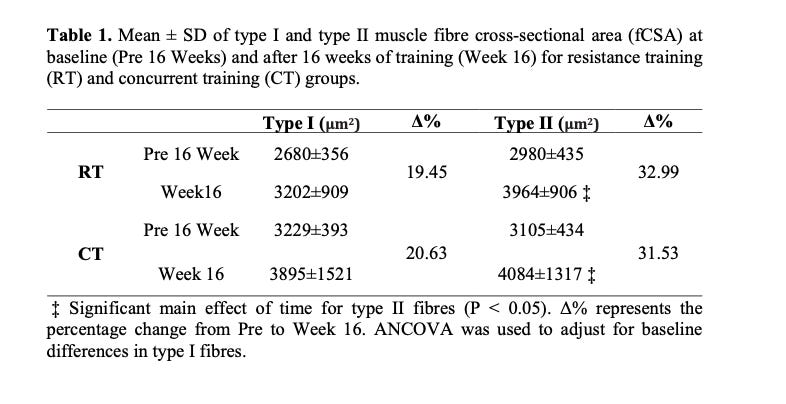

Despite weaker strength gains, muscle fibre hypertrophy was remarkably similar between the two groups: type II fibers grew by ~19% in the resistance training group and ~18% in the concurrent training group. On the other hand, type I fiber size didn’t change in either group, and no clear patterns suggested an interference effect.

This is one of the most important results in the paper—concurrent training blunted strength gains, but did not impair type II muscle fiber hypertrophy. That alone tells us the interference effect is unlikely to be explained by “failure to grow muscle.” An important part of this is likely that resistance training volume (sets x reps x load) was identical between groups (by design).

The anabolic response is preserved during concurrent training

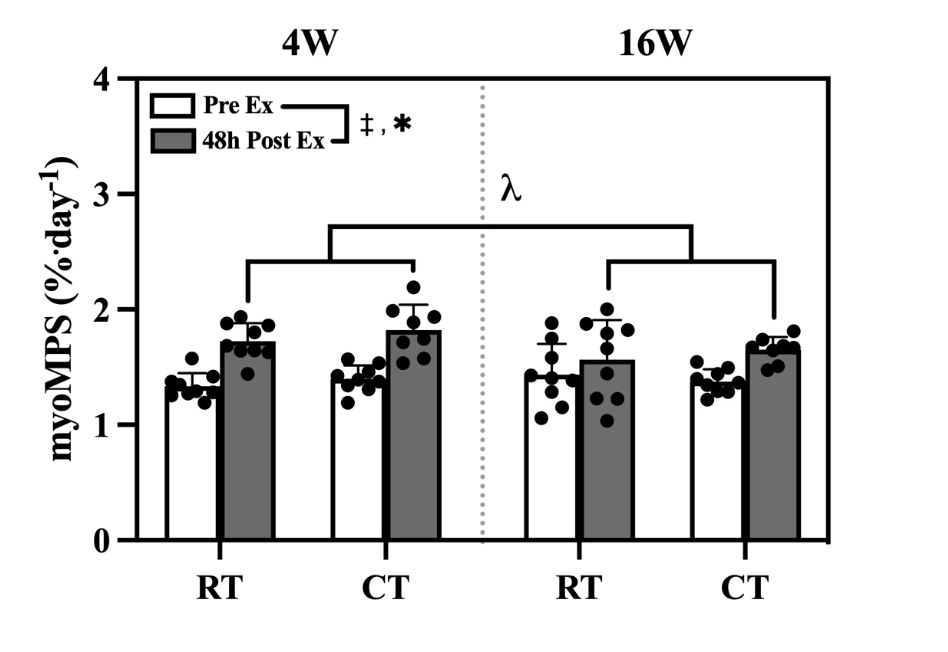

If endurance training were shutting down the hypertrophy machinery, you’d expect lower myofibrillar protein synthesis in the concurrent group, but that didn’t happen.

The acute increase in myofibrillar protein synthesis (48 hours post-exercise) increased similarly in the concurrent training and resistance training-only groups when assessed at week 4 and week 16. And even though the post-exercise rise in protein synthesis was smaller at week 16 than week 4 (a normal training adaptation), it occurred in both groups, and was clearly preserved in the concurrent group—HIIT did not suppress the protein-synthesis response supporting hypertrophy.

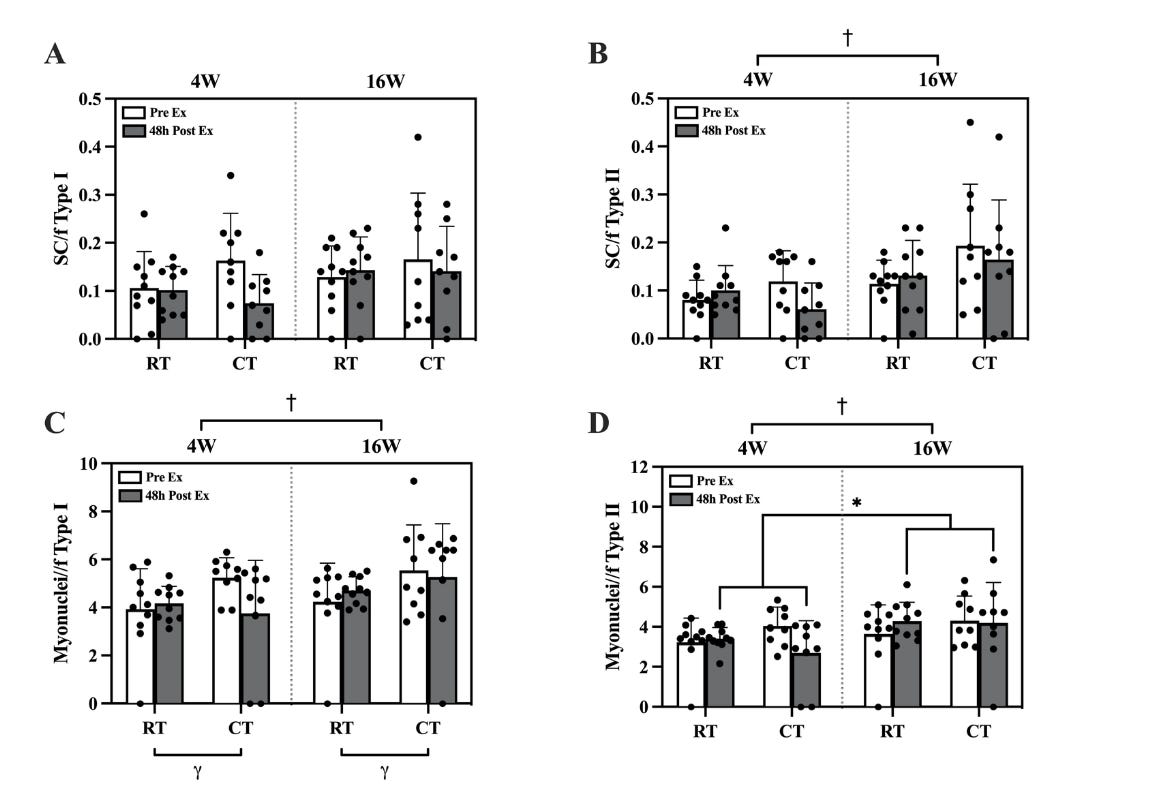

The cellular infrastructure that supports hypertrophy also expanded over time, with increases observed in type II muscle fiber satellite cell content and type I and type II muscle fiber myonuclear number. Again, this suggests that endurance training/HIIT doesn’t impair the cellular processes associated with muscle growth (in fact, acute post-exercise increases in satellite cells and myonuclei were sometimes larger in the concurrent training group).

Finally, those myogenic regulatory factors showed modest shifts over time, but nothing consistent with suppressed hypertrophy.

Here’s the cleanest way I can interpret these results.

Muscle growth machinery (protein synthesis, fibre hypertrophy, satellite cells, myonuclei) was largely preserved with concurrent training, but maximal strength improved less, strongly supporting the notion that neuromuscular and performance-level factors—not impaired muscle growth or blunted anabolic signaling—are the primary driver of “interference.”

This makes sense. Strength is not just muscle size. It depends on motor unit recruitment, firing rates, coordination, and (perhaps most importantly), freshness and recovery.

Concurrent training likely compromises some of those elements, especially when it involves high-intensity aerobic exercise, even when muscle remodeling proceeds normally. If you’re “too tired” (neuromuscularly speaking) from a HIIT workout or a 2-hour long run, you won’t be as strong as you will be in a “fresh” state. But you won’t be as aerobically fit either…

So, if your mental model is “cardio kills gains,” this study doesn’t support that—at least not in the way it’s often framed. The interference effect isn’t a single phenomenon. It depends on which adaptation you care about most, and whether the limiting factor is molecular, cellular, or neural.

And that distinction matters far more than arguing about whether AMPK “turns off” mTOR or postulating about some complex, molecular puzzle.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 30% off their order this week. So stock up!

ProBio Nutrition—the all-in-one supplement that I use every single day—is offering 20% off. My preference is the tangy orange flavor, but they also sell an unflavored “smoothie booster” that’s great in a shake, smoothie, or juice.

Equip Foods makes some of the cleanest, best-tasting protein products around. I am absolutely obsessed with their Prime grass-fed protein bars (the peanut butter ones are to die for). Take up to 10% off site-wide!

Very interesting to read and the findings correlate well with my own experience when I used to try building bigger muscles in the upper body while maintaining my running mileage and volume. It didn't work out for me, probably because of the in the article mentioned fatigue from the endurance training, which has always been what I prioritized.

I am no longer interested in building "as big muscle as possible" in the upper body, aka maximal hypertrophy gains, but I still enjoy lifting weights and I think it has a lot of benefits in regards to long term health and core-stability (which subjectively improves my running economy and posture a lot). I am thus looking for a strength training "style" that doesn't impair my running too much, but still carries some of the benefits from above: What do you think of the rep range that is not mentioned in the study: the often-called "strength-endurance rep range" with 15 or even 20+ reps?

I was thinking about trying a circuit- or superset-style workout with upper body and core exercises using lighter weights but higher repetitions. I intentionally don't include lower body exercises because I experienced they caused too much fatigue and interfered too much with my running volume that promotes enough stimulation already by itself (also because I am doing a lot of vert and I regularly include days with very long and steep Up and Down runs that seem to complete with flat running perfectly).

Again, my main intention with a strength workout like this is enjoyment, overall health benefits and some core-/upper body strengthening (without adding too much muscle mass) for improved running economy (I am running a lot with poles, so I kinda think of myself as "Nordic" runner anyway ;) ).

Would be interesting to know what you think about that!

For example: BB Rows, Bench Press, weighted Planks, Russian Twists, Overhead Press, ... etc. with 15-25 reps (except for the Planks and the R. Twists), 30-60sec rest in between sets, and always "super-setting" two exercises with different focuses, like Push to Pull).

Great explanation Brady thanks. As a runner I would want to get stronger rather than bigger muscles- is that possible?

sounds like strength training does the opposite?