Physiology Friday #302: When Does Performance Peak and Decline throughout Life?

A 50-year-long study paints the clearest picture yet of how capacity changes with age.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter and deals on products, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, Equip Foods, and ProBio Nutrition can be found at the end of the post.

I couldn’t wait to write about today’s study. It might be one of the most important and informative ones ever published on aging and physical performance.

The study followed the same people for nearly 50 years and found something illuminating: peak physical capacity arrives early (earlier than we think), starts to decline before age 40, and the slope of decline steepens with age.

And the most surprising (and actionable) part? Aging doesn’t just lower performance, it also widens the performance gap between people, suggesting the “inevitable” path of aging is modifiable.

This study will change how you think about your own “performance trajectory.”

The study tracked physical capacity across almost the entire “adult arc” of life, from age 16 to age 63, in 427 individuals (48% women) from a population-based Swedish cohort known as the Swedish longitudinal cohort for Physical Activity and Fitness, with five waves of measurements—at age 16, 27, 34, 51, and 63.1

This type of long-term follow-up in the same group of individuals is almost unheard of.

Gathering data on the same people decades apart, rather than relying on cross-sectional comparisons of different people, is crucial to understanding aging because it prevents misleading comparisons confounded by lifestyle factors. It tells us how physical aging occurs within a person rather than between different people.

To measure physical capacity, researchers focused on three domains:

Aerobic capacity—assessed with a 9-minute run test at age 16 and a submaximal cycling test at ages 27, 34, 52, and 63, and then converted into VO2 max.

Upper-body muscular endurance—assessed using bench press repetitions to failure using 20 kg (for men) or 12 kg (for women).

Muscular power—assessed using a standing vertical jump test.

What’s novel about the analysis is that they didn’t just focus on if and by how much physical capacity in each domain declines with age, but also when peak physical capacity occurs, the percent change in each domain per year after peak, and how much the spread in physical performance widens between people with age. The latter piece is perhaps one of the most underappreciated findings of the entire paper.

Physical aging is inevitable

Here’s the headline finding—peak physical capacity occurs before age 36, and after age 40, the decline is shared across domains, accelerates as people get older, and is unavoidable… but the rate is modifiable!

Regardless of the domain being measured, most people’s physical capacity peaks around or before age 36, and the annual loss in capacity is about 1% per year shortly after the peak and accelerates to more than 2% per year later on. The average loss in physical capacity from peak to age 63 is about 37%, spanning roughly 30% to 48% depending on the domain (more on that below).

This is a very different story from what we’re currently told about aging—that things start to go downhill around age 50 or 60. These data would suggest that the slide starts earlier than most people realize and may be a “built-in” biological phenomenon.

Alright, let’s now get to each physical performance domain, because these data are even more interesting than the general trend.

All physical domains decline with age (but not equally)

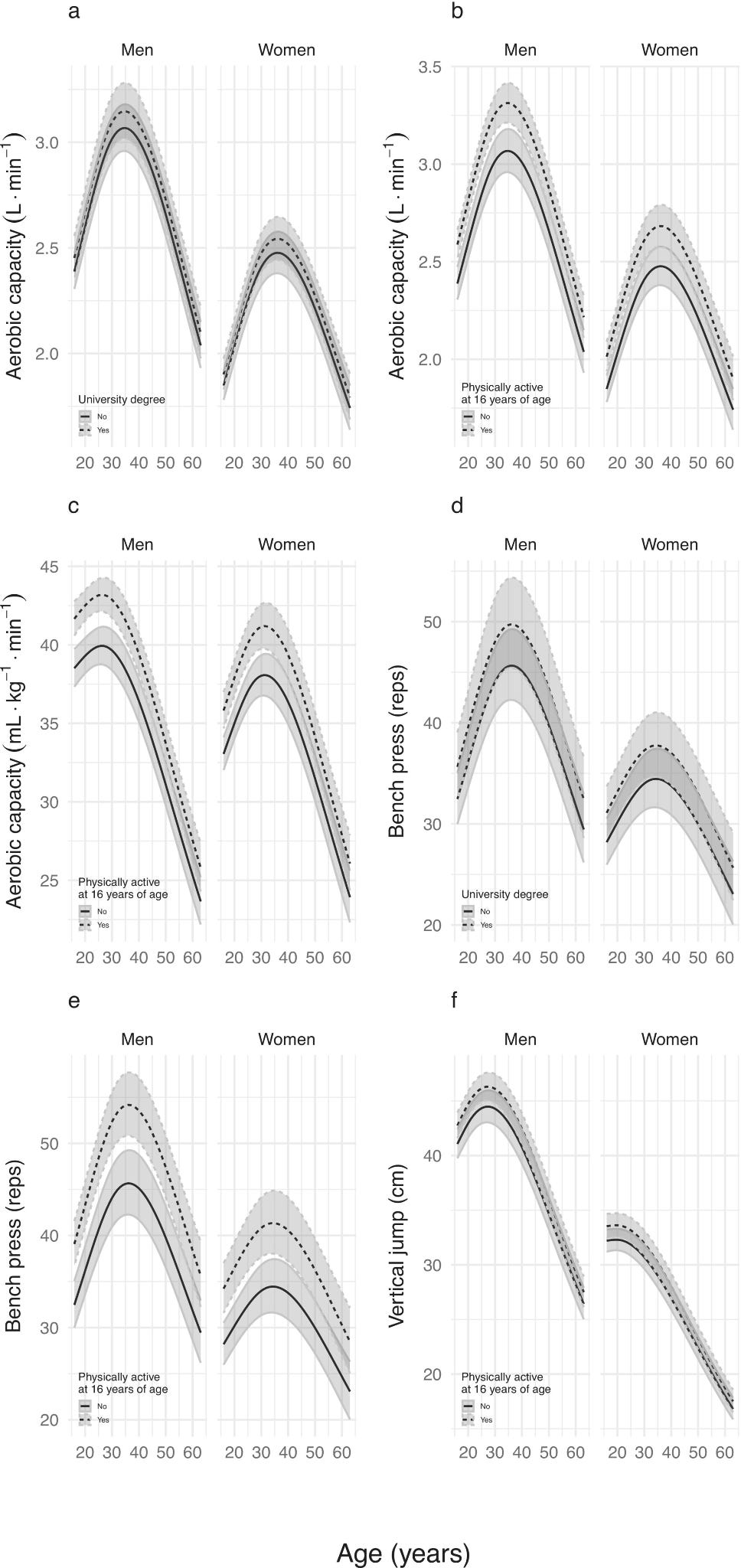

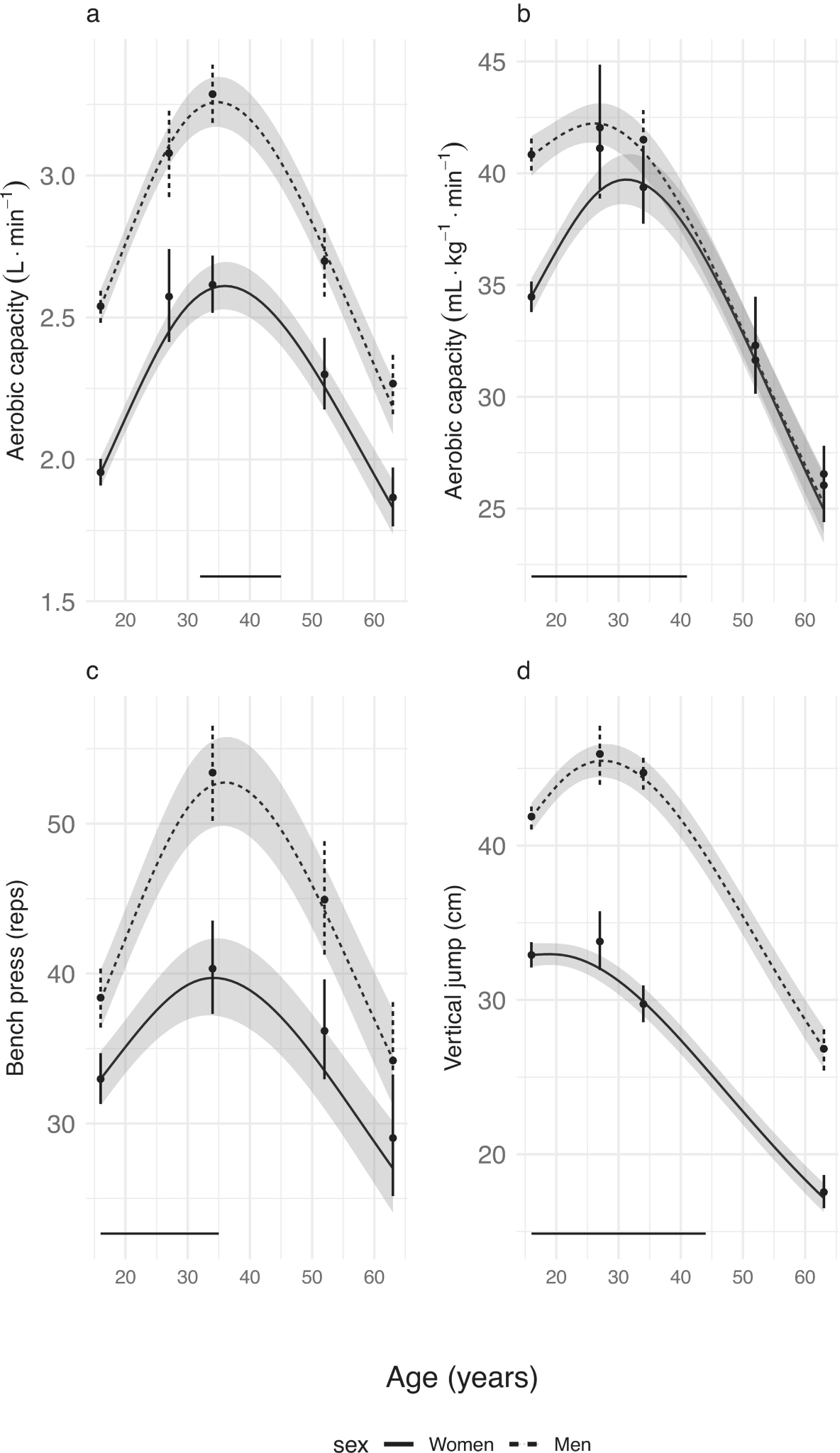

Absolute aerobic capacity (VO2 max in Liters per minute) peaks at age 35–36, after which it declines by 0.5% per year up to age 40 and then up to 2% per year by age 63. And across the entire population, absolute aerobic capacity is 30–33% lower at age 63 than at peak capacity (age ~35).

Relative aerobic capacity (VO2 max in mL/kg/min) follows the same trend and is perhaps the more important measure of aerobic fitness because it blends the “engine size” with changes in body mass (which also changes with age). The peak age differed between men and women: men peaked at 26 (42.2 mL/kg/min) while women peaked at 31 (39.7 mL/kg/min). But the rate of decline was similar—from age 40 onward, relative VO2 max dropped by 1.1% per year. By age 63, the rate of decline was 2.2% per year. And the cumulative decline in aerobic capacity from peak to age 63? It was 37% in women and 40% in men.

These numbers are pretty drastic, especially the cumulative decline. They indicate that by age 63 (early old age), most people have lost nearly half of their peak aerobic capacity.

Looking at muscular endurance, the peak age was similar to that for aerobic capacity—age 34 in women and age 36 in men—and the rate of decline accelerated from around 1% in the early years after peak to just over 2% per year by age 63. The cumulative decline in muscular endurance from peak to age 63 was 32% for women and 35% for men.

Last is muscular power (vertical jump). This domain had a vastly different trajectory than aerobic capacity and muscular endurance. It peaked early, at age 19 in women and age 27 in men, after which it declined by 1–2% per year from age 30 onward. By age 63, men and women had lost 41% and 48% of their peak muscular power, respectively.

Aging increases the performance inequality

One of the most novel aspects of this study was that it quantified how much between-person variance increases from adolescence to early old age. In other words, how does the gap in performance (the “spread”) change between people as they get older?

Depending on the capacity, variance increased roughly 3-fold to 25-fold!

To use specific examples, the variance in relative aerobic capacity was 25 times higher at age 63 than at age 16, while for muscular endurance it was 3 times higher, and for muscular power it was 5 times higher.

What does this mean practically? At age 16 (and perhaps even up to peak capacity), the performance gaps between any two people are generally low, but by age 63, two people with the same chronological age may have a wildly different “functional age,” and the gap between them is much bigger than it was at age 16.

I think this is much more than a statistic. It’s telling us that while aging may be a universal process, performance is an individualized outcome shaped by one’s environment, lifestyle, and physiology.

That brings us to the final component of this paper—the influence of physical activity.

People who reported being physically active at age 16 (though admittedly through a crude “yes/no” answer on a questionnaire) showed a higher capacity later on in life at every age. That much might seem obvious. But what’s interesting is that switching from being “inactive” to “active” at any age was associated with meaningful gains across domains—a 6–7% bump in aerobic capacity, an 11% bump in muscular endurance, and a 4% bump in power output.

However, activity didn’t appear to shift the age of the peak in physical performance, just the slope of the decline after the peak. This would suggest that when we reach our peak capacity may be constrained… perhaps even encoded in our biology. But how fast we decline after we reach our peak (and the ceiling we do reach) is meaningfully modifiable.

They reinforce that conclusion by adding some data comparisons from the literature on master athletes. At age 63, the general population maintained only about 65% of their peak aerobic capacity and muscular endurance, whereas athletes of the same age maintain about 80%. And for muscular power, men and women from the general population have kept only about 50–60% of their peak capacity at age 63, but it takes athletes until age 75 to hit a comparable level of decline.

The narrative here is clear: aging is inevitable, but how fast you age is negotiable.

Why did I start this newsletter by emphasizing how excited I was to share this paper? Hopefully, my discussion above made that clear, but if not, it’s because I think it radically shifts our perception about the trajectory of aging and how modifiable it is (in addition to just being a really cool and novel design…just a unicorn of a study).

If the rate of aging is innate—as the data here would suggest—but the starting point in our position on that hill (how high we peak) is up to us, it raises an important question: Are we really fighting aging when we exercise, or are we simply just fulfilling the maximum potential of a decaying system?

Maybe exercise isn’t magic or medicine. It’s proper maintenance for the machine, without which we experience premature decline.

We often accept the average as being inevitable, especially when it comes to health. We see the decline as the tragedy.

Maybe the real tragedy is that most people never get close to seeing what their 60- or 70-year-old body is capable of.

We are normalizing disuse and calling it aging. And I think it’s time to change that.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 20% off their order.

ProBio Nutrition—the all-in-one supplement that I use every single day—is offering 20% off. My preference is the tangy orange flavor, but they also sell an unflavored “smoothie booster” that’s great in a shake, smoothie, or juice.

Equip Foods makes some of the cleanest, best-tasting protein products around. I am absolutely obsessed with their Prime grass-fed protein bars (the peanut butter ones are to die for). Take up to 10% off site-wide and up to 35% off a subscription.

"Maybe the real tragedy is that most people never get close to seeing what their 60- or 70-year-old body is capable of". 100% correct. Just look around. Most people don't even try to stay in shape by 60, much less pursue their potential at that age. I think that the best age-group athletes are the ones dumb enough to think they can still train like they could in their 30s and 40s :)

Brady, thanks for this post. As a 64-year-old runner, I am a prime example of the findings from that study. Sometimes I shift it into high gear, and there's nothing! Oh well. I focus on my age cohort. Recently, I ran a half-marathon in Dallas. The goal was to finish in the top third of my age group. I finished in the top 30%! I was happy with the result, and it was my best time in 4 years. I'm just grateful I'm still out there trying to poke old Father Time in the eye. Love your Substack!