Physiology Friday #303: A New Look at Arrhythmia Risk in Endurance Athletes

Training load may not be the "smoking gun" when it comes to heart risk.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter and deals on products, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, Equip Foods, and ProBio Nutrition can be found at the end of the post.

Exercise is medicine. But like all medicines, the dose makes the poison.

Can “too much exercise” send you to an early grave?

That argument has been around for decades, but the scientific story here is complicated. At a population level, regular exercise is overwhelmingly protective for cardiovascular disease and mortality. But when you zoom in on very high lifetime training volumes—especially in older men—the literature starts to show a more mixed picture.

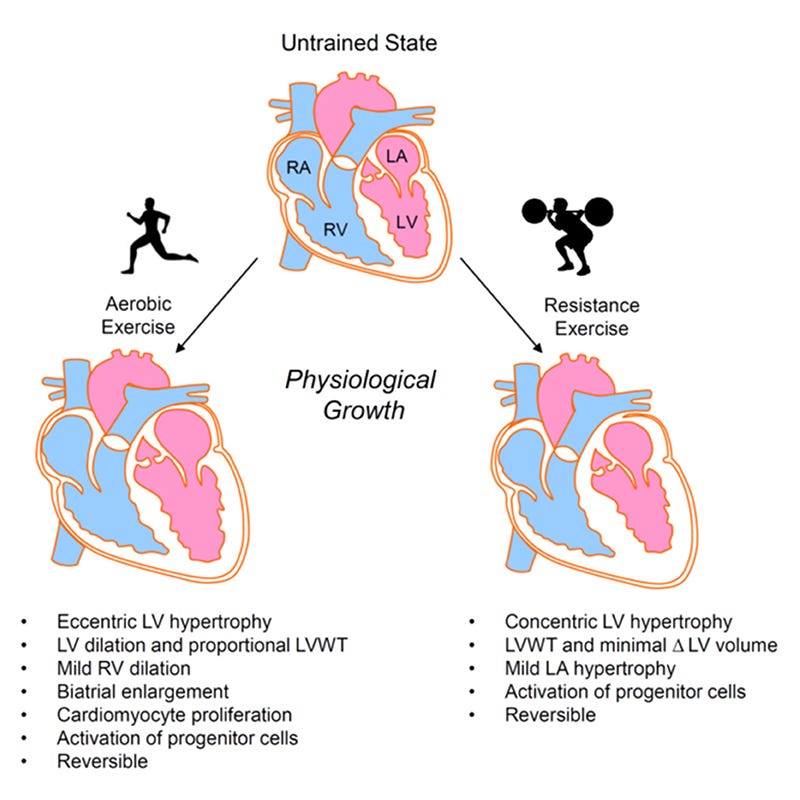

The best-established example is atrial fibrillation (AFib for short). Long-term endurance athletes, particularly male and master athletes, show higher AFib rates than sedentary peers. That’s likely due to a mix of structural remodeling (bigger chambers of the heart known as the atria), autonomic shifts (more parasympathetic tone), and repeated inflammation/strain from intense exercise and racing built up over years and decades. While it’s concerning because it can raise stroke risk and make you feel lousy or limit performance, in endurance athletes, AFib is usually manageable and treatable.

Ventricular arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms originating in the larger chambers of the heart known as the ventricles) are a different beast: they’re less common, potentially more serious, and much harder to predict. The debate in sports cardiology is whether endurance exercise can create a ventricular arrhythmia problem (by causing scarring or ventricular remodeling), or whether exercise mostly reveals an existing vulnerability (a subtle heart abnormality, a genetic predisposition, or a pre-existing scar) by adding a potent trigger.

But in real life, endurance athletes often look normal on routine screens, and the arrhythmias can be intermittent. Which raises a practical question: is there something about how we train—volume, intensity, pattern—that meaningfully changes risk? Or is this mostly about who you are and what your heart tissue looks like?

A new study tries to answer that with unusually granular data and very rigorous measurement choices.1 It’s probably the most in-depth characterization of the training-arrhythmia risk relationship I’ve seen, and the conclusions (I think) are incredibly important.

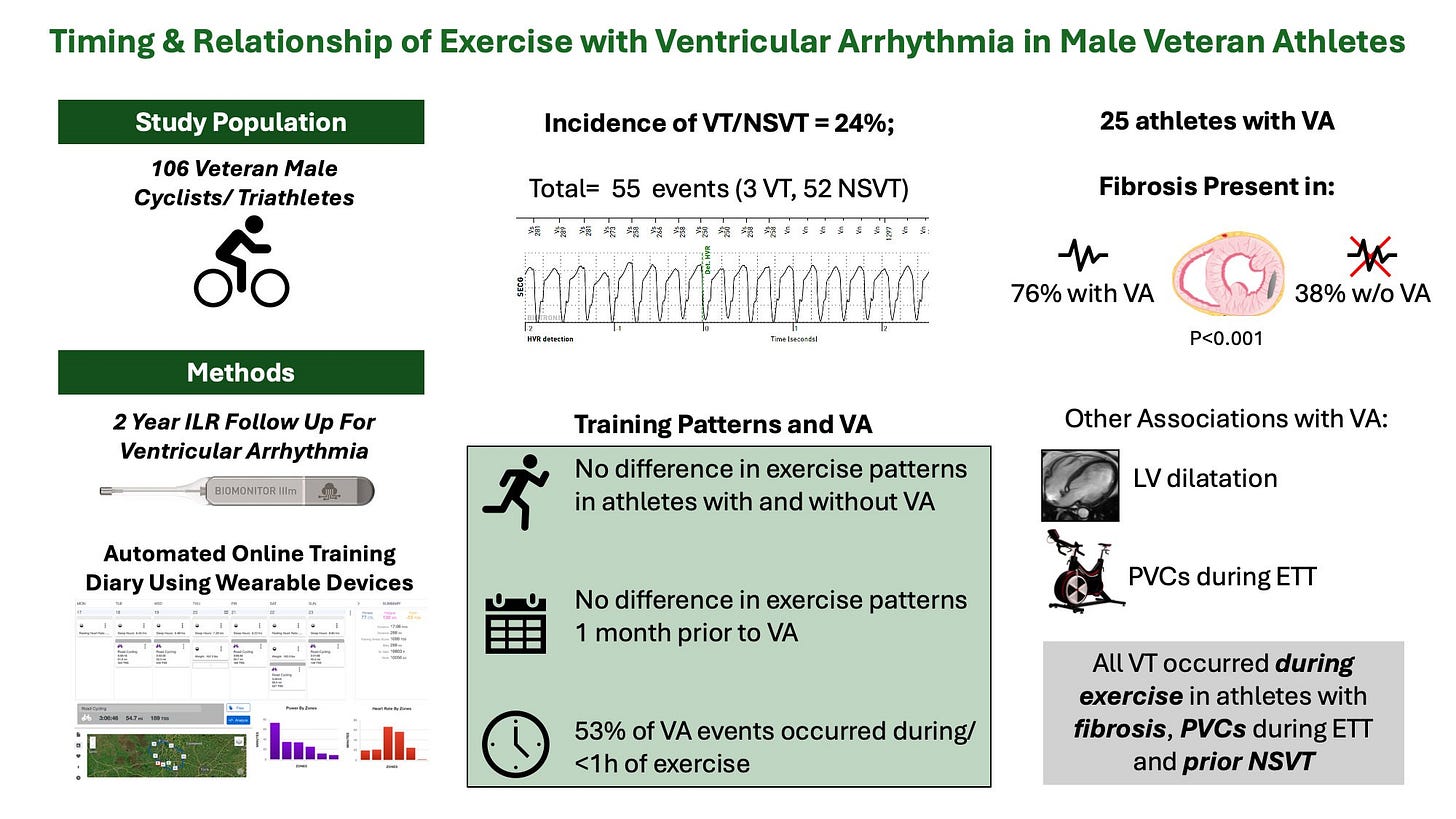

Researchers recruited 106 “healthy” veteran male endurance athletes (cyclists/triathletes), all >50 years old, with a long history of heavy training (>10 hours/week for >15 years). Importantly, they excluded anyone with known cardiovascular disease and athletes with symptoms that might hint at disease (chest pain, palpitations, shortness of breath, or fainting).

Everyone underwent a clinical exam plus a 12-lead ECG (heart rhythm monitoring), cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to detect scarring and fibrosis of the heart, and a supervised maximal exercise test to measure maximum heart rate, performance variables, and anchor their training load.

The training load measurement is where the study gets detailed. Athletes used computerized exercise tracking devices and synced their workouts to an online diary (TrainingPeaks). Training wasn’t just volume; they quantified intensity in multiple ways using frequency, duration, and distance from the recorded sessions. They also calculated Training Stress Score (TSS) as their primary training load metric and broke intensity into time-in-zones (Z1–Z6), using standardized zone cutoffs relative to each athlete’s physiology.

This lets them ask a more precise question than how much athletes trained. They can ask about training intensity distribution to figure out if, say, spending more time in zone 2 or doing more threshold intervals raises one’s risk of a ventricular arrhythmia.

Every participant received an implantable loop recorder—a small device placed under each athlete’s chest skin that was programmed to record a fast and arrhythmic heart rate faster than the participant’s maximal heart rate from the exercise test, for ≥8 consecutive heartbeats. Athletes logged symptoms in a linked patient app. Here’s how they defined a “positive” arrhythmia event:

Sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT): ≥30 seconds of ventricular rhythm at ≥100 bpm

Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT): ≥3 consecutive ventricular beats lasting <30 seconds

How often did arrhythmias show up?

During a follow-up period of just over 2 years (796 days), 55 ventricular arrhythmia events occurred in 25 athletes (23.5% of the participants): 52 NSVT (94.5% of all events) and 3 sustained VT (5.5% of all events)

Of the 55 events:

29 (52.7%) occurred during or within 1 hour of exercise

14 (25.5%) occurred 1–24 hours after exercise

12 (21.8%) occurred >24 hours after exercise

5 (9.1%) were nocturnal (occurred at night)

The incidence rate was 0.4 events per 1000 hours of exercise vs 0.01 per 1000 hours of non-exercise time. That’s a 28.6× higher event rate around exercise exposure.

Here’s where the study gets interesting. It identifies myocardial fibrosis as the clearest risk factor for ventricular arrhythmias in athletes. Among athletes who experienced an arrhythmia, 76% had evidence of fibrosis/scarring of the heart, compared to just 38% of athletes who did not experience an arrhythmia.

Furthermore, all 3 sustained VT cases (sustained VT being the longer-lasting, more serious form) occurred during exercise in athletes with fibrosis, and each was preceded by NSVT.

Premature ventricular contractions (or PVCs; early heartbeats occurring during maximal exercise testing) were another clear discriminator of who would go on to develop an arrhythmia during follow-up.

During exercise testing, 21/25 (84.0%) of athletes in the arrhythmia group experienced PVCs, compared with 35/74 (47.3%) in the no-arrhythmia group.

The influence of training characteristics

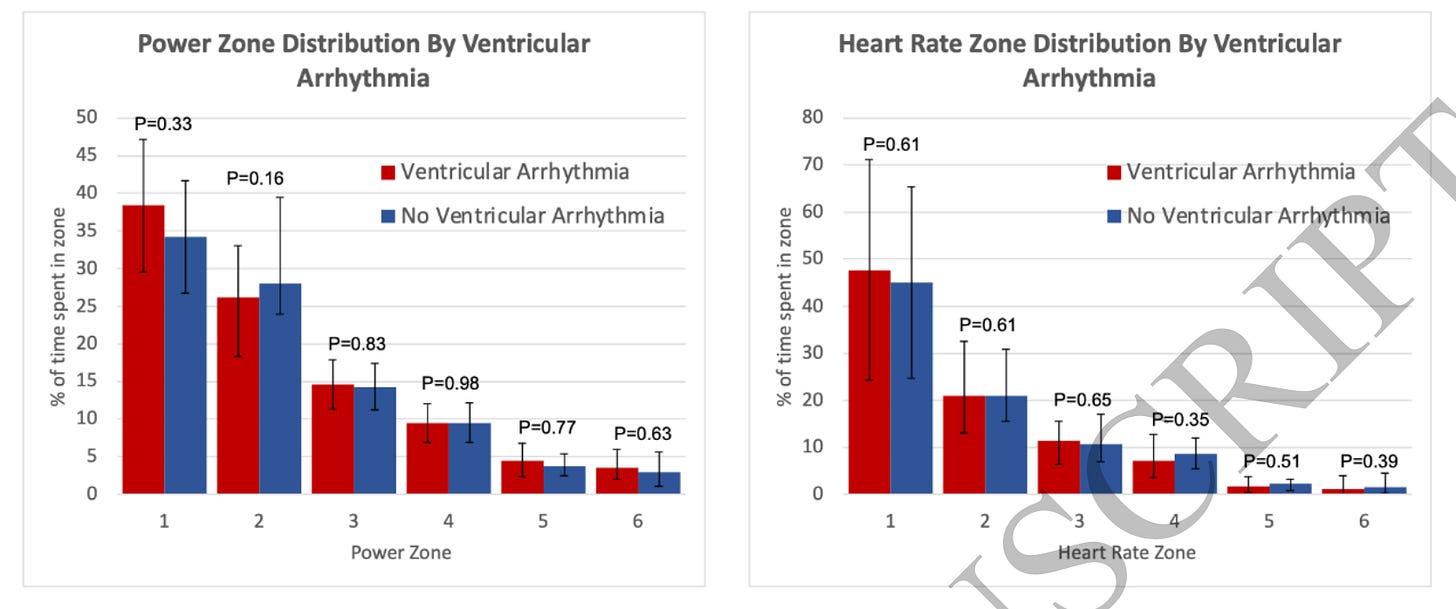

From the objective (TrainingPeaks/exercise device) data, we can see that most training characteristics were basically identical between groups who did and did not experience an arrhythmia.

Weekly total exercise: 7.2 ± 3.1 hours (no arrhythmia) vs 7.2 ± 3.0 hours (arrhythmia)

Weekly cycling distance: 1,17.2 ± 57.3 miles vs 1,10.0 ± 46.1 miles

Weekly TSS: 338 (229–484) vs 366 (284–448)

Annual cycling distance: 6,094 ± 2,979 miles vs 5,722 ± 2,400 miles

Monthly session frequency: 14.5 (10.2–18.8) vs 16.4 (12.6–20.1)

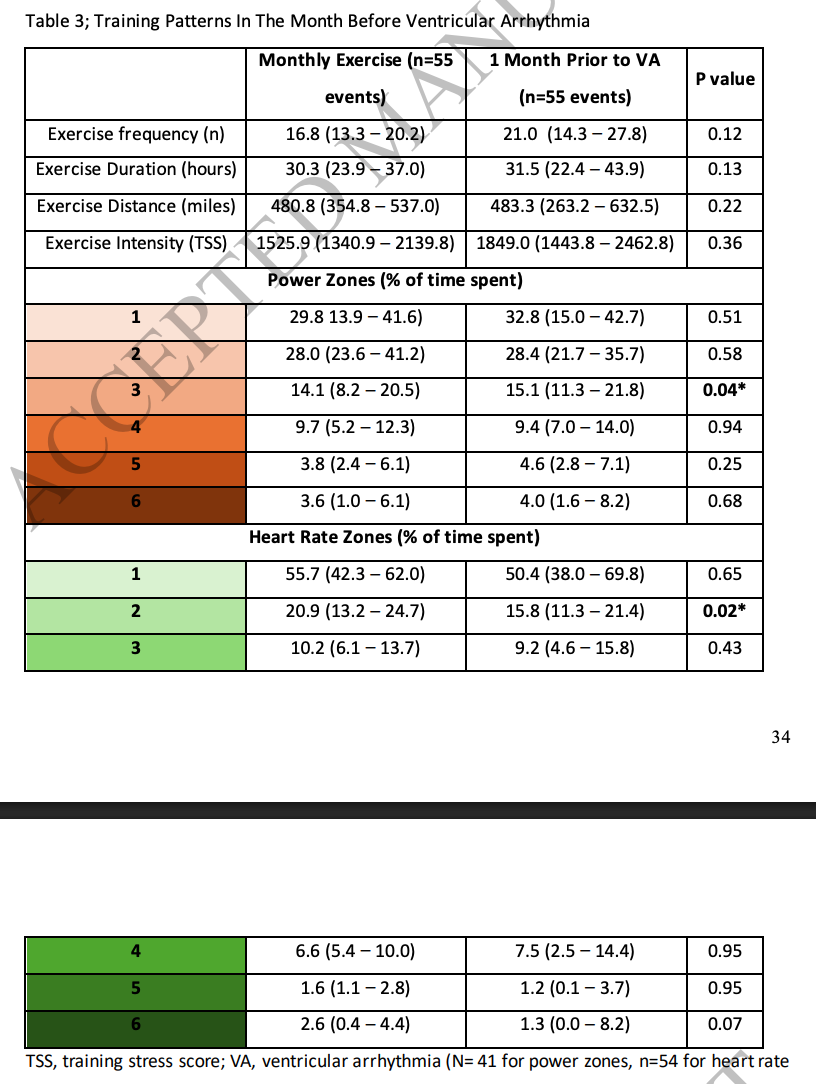

They also looked for a classic endurance pattern: a big “training spike” in the weeks before an event. That didn’t show up in a clear way either.

Even in the month before each arrhythmic event (within each athlete), the big training load variables weren’t much different compared to the rest of the time when they didn’t experience an arrhythmia. Obviously, we can see small advantages here in the pro-arrhythmia months, but most didn’t reach statistical significance.

Frequency: 16.8 (no arrhythmia) vs. 21.0 sessions (arrhythmia)/month

Duration: 30.3 vs. 31.5 hours/month

Distance: 480.8 vs. 483.3 miles/month

TSS: 1,525.9 vs. 1,849.0 per month

The only meaningful-looking shifts were distributional (time in zones), not total load—athletes spent more time training in power zone 3 and less time in heart rate zone 2 in the month before experiencing an arrhythmia when compared to their “normal” month of training.

Power zone 3 (tempo): 14.1% (no arrhythmia) vs. 15.1% of time

HR zone 2 (endurance): 20.9% (no arrhythmia) vs. 15.8% of time

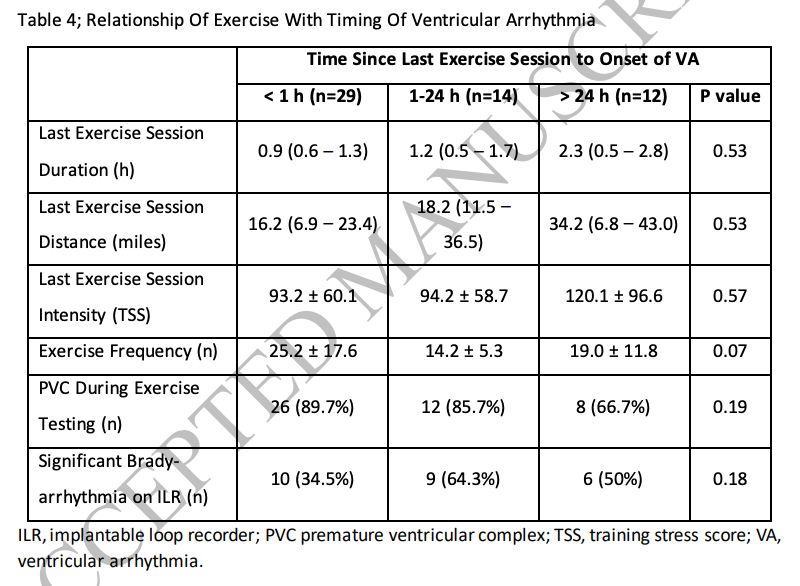

And when they grouped events by how soon after exercise they happened (<1 hour after exercise, 1—24 hours after, or >24 hours after), the preceding session metrics weren’t clearly different:

Last-session duration: 0.9 hours (<1h) vs 1.2 hours (1–24h) vs 2.3 hours (>24h)

Last-session distance: 16.2 miles vs 18.2 miles vs 34.2 miles

Last-session TSS: 93.2 vs 94.2 vs 120.1

What’s this telling us? Doing more intensity, exercising for longer, or having a sharp spike in intensity doesn’t necessarily mean you’re more likely to experience an arrhythmia sooner after your exercise session (like 1 hour after) versus later (24 hours or more after). Again, I can see some trends here—larger training duration/distance/TSS did appear to make arrhythmias happen later after exercise as opposed to sooner. But I’m not quite sure there’s a clean interpretation there.

Other physiological differences worth noting

A few other differences that seem relevant:

Athletes who experienced arrhythmias during the study had larger left ventricular volumes, on average (about 7.5% larger), compared to athletes without arrhythmias.

Cycling functional threshold power (FTP) was similar between groups—250 Watts (arrhythmia) vs. 239 Watts (no arrhythmia).

Studies like this are why I’m still not persuaded by blanket claims that “excessive endurance exercise is heart-harmful.” That conclusion often gets built on proxy markers (e.g., CAC), small cohorts, or dramatic anecdotes, and then generalized to millions of people whose real endpoint risk is still seemingly low. This paper doesn’t let anyone off the hook (ventricular arrhythmias aren’t trivial, and fibrosis was detected in a meaningful number of the athletes), but it does push us toward a more discriminating view that risk factors and substrate may matter as much or more than the training itself.

In other words, heart risk may be less about demonizing endurance exercise and more about getting better at identifying who is susceptible, and why.

Because in this cohort, the guys with arrhythmias didn’t have higher weekly hours, distance, or training stress scores (as we might expect if more exercise is more harmful). Instead, myocardial fibrosis was associated with a much higher observed arrhythmia risk (fibrosis roughly tripled risk), and then acute exercise exposure clustered tightly around when events actually happened (nearly 29× higher event rate during and near exercise than away from it).

So the actionable thing for veteran endurance athletes (or those of us hoping to become them) is to not ignore symptoms during exercise, take abnormal heart sensations seriously, and recognize that the best risk reduction strategy may be identifying whether you have an underlying risk like fibrosis, rather than trying to perfectly tweak your intensity distribution.

When it comes to your heart, risk might be influenced more by who you are (and what your heart looks like) than your weekly mileage or how much time you’re spending in zone 2.

And if we really are to believe endurance exercise is harmful, in the words of legendary runner and writer Amby Burfoot: “Show me the bodies in the street.”2

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 20% off their order.

ProBio Nutrition—the all-in-one supplement that I use every single day—is offering 20% off. My preference is the tangy orange flavor, but they also sell an unflavored “smoothie booster” that’s great in a shake, smoothie, or juice.

Equip Foods makes some of the cleanest, best-tasting protein products around. I am absolutely obsessed with their Prime grass-fed protein bars (the peanut butter ones are to die for). Take up to 10% off site-wide and up to 35% off a subscription.

Wasim Javed, Benjamin Brown, Bradley Chambers, Eylem Levelt, Lee Graham, John P Greenwood, Sven Plein, Peter P Swoboda, The Timing and Relationship of Ventricular Arrhythmia with Exercise Patterns in Veteran Male Endurance Athletes, European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 2026;, zwag021, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwag021

I wrote a follow-up expanding on your analysis here — especially on the screening blind spot for athletes. Thanks for surfacing the paper.

https://open.substack.com/pub/jameslombardo/p/the-blind-spot-in-athlete-heart-screening?r=2d6tw0&utm_medium=ios&shareImageVariant=overlay

Great post. The distinction between training load and underlying risk factors was helpful. A nice counter to the “too much exercise is bad” oversimplification.