Physiology Friday #304: How the Tour de France Stresses the Body

A physiological case study of one of the most grueling races on the planet.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter and deals on products, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, Equip Foods, and ProBio Nutrition can be found at the end of the post.

“Overtraining” is a vague term, and that’s an understatement.

Nobody in exercise science really knows how to define it. And we don’t really have any biomarkers to diagnose it (that’s not for a lack of trying).

Sure, we can feel fatigued, chronically sore, or lack motivation to train. These correlate well with training load. A poor capacity to adapt (you’re not getting better with each workout) is also one of the more well-accepted markers of overtraining/overreaching (as it’s more commonly referred to). But ask two different coaches what overtraining is, and you’ll probably get two completely different answers.

We lack a precise characterization of overtraining for several reasons, but one of the main ones is that we just don’t have a good model of how to “overtrain” people. What’s the minimum amount of hard exercise someone needs to do before they hit their breaking point? And how can you implement this into a study? On the other hand, maybe it’s all about a lack of recovery rather than too much training per se.

Without the ability to subject people to the right overtraining stimulus, it’s impossible to define the “signature” of an overtrained athlete.

That’s what makes today’s study so interesting—it uses what is perhaps the most demanding athletic endeavor—the Tour de France—and uses it as a kind of physiological stress test for human metabolism.1

Cyclists competing in the Tour de France are operating at (or above) the upper limits of sustained human metabolic energy expenditure—they’re burning nearly 4–5 times their basal metabolic rates (upwards of 8–10 thousand calories per day) for three weeks. During the Tour, athletes cover 3,404 kilometers (2,115 miles) with more than 56,000 meters of climbing across 19 days (including 2 blissful rest days).

If we want a model of excessive exercise (and diminished recovery), the Tour de France is it.

By characterizing the body’s response to this grueling event, researchers hoped to uncover a “metabolite signature” of excessive exercise and, hopefully, in the process, discover novel biomarkers of overtraining that could be used to diagnose when elite athletes (and perhaps the rest of us, too) are getting too close to the edge.

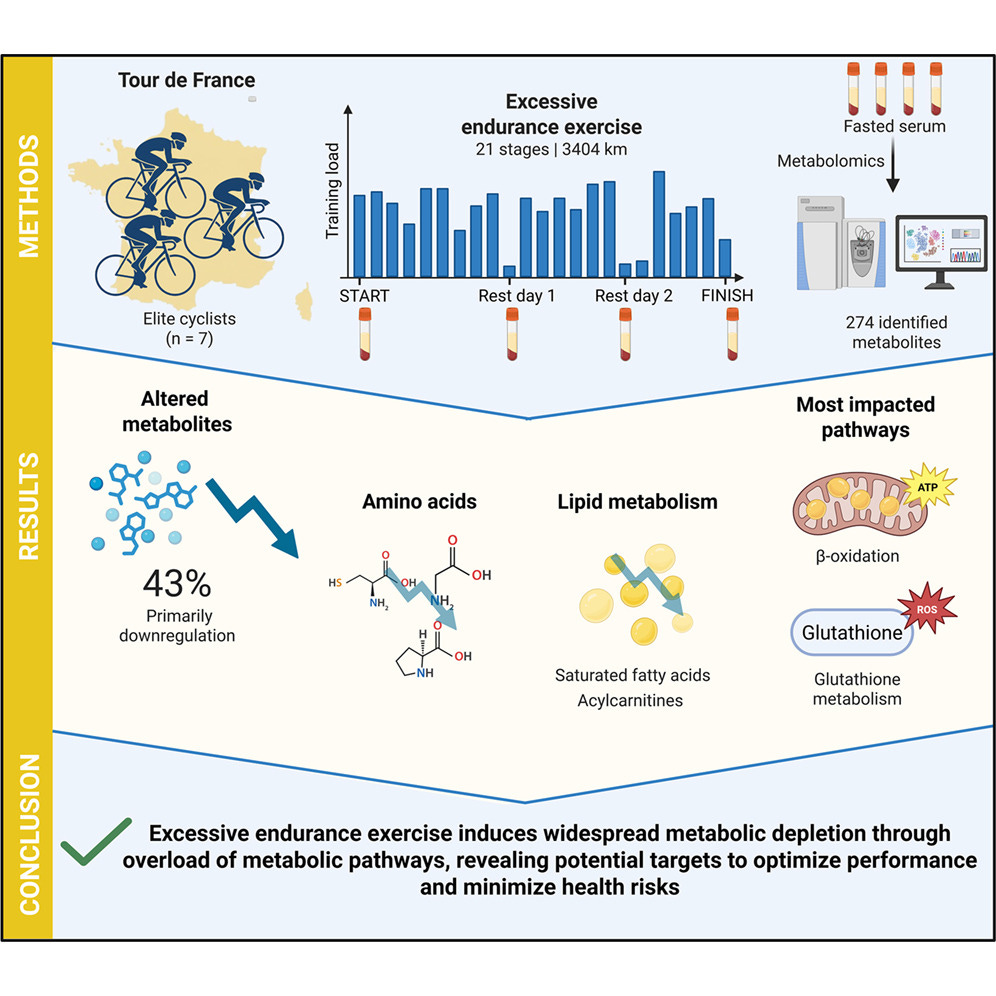

The researchers followed 7 professional male cyclists during the 2023 Tour de France (one rider crashed and was subsequently excluded), collecting fasting blood samples in the morning at four time points: the start of the race, on rest day 1 (day 10 of the Tour), on rest day 2 (day 17 of the Tour), and the finish.

What they were mainly looking at in this study was blood metabolites—small molecules circulating in the blood that come from normal chemical reactions in the body. They’re the “chemical fingerprints” of what the body is doing and include things like fuel molecules (glucose, fatty acids, ketones), amino acids, byproducts of energy production (lactate, citrate), and signals and stress markers tied to inflammation and oxidative stress. Measuring a wide range of metabolites is basically taking a snapshot of the body’s metabolic state—how you’re producing energy, what you’re burning, what you’re conserving, and what systems might be under strain.

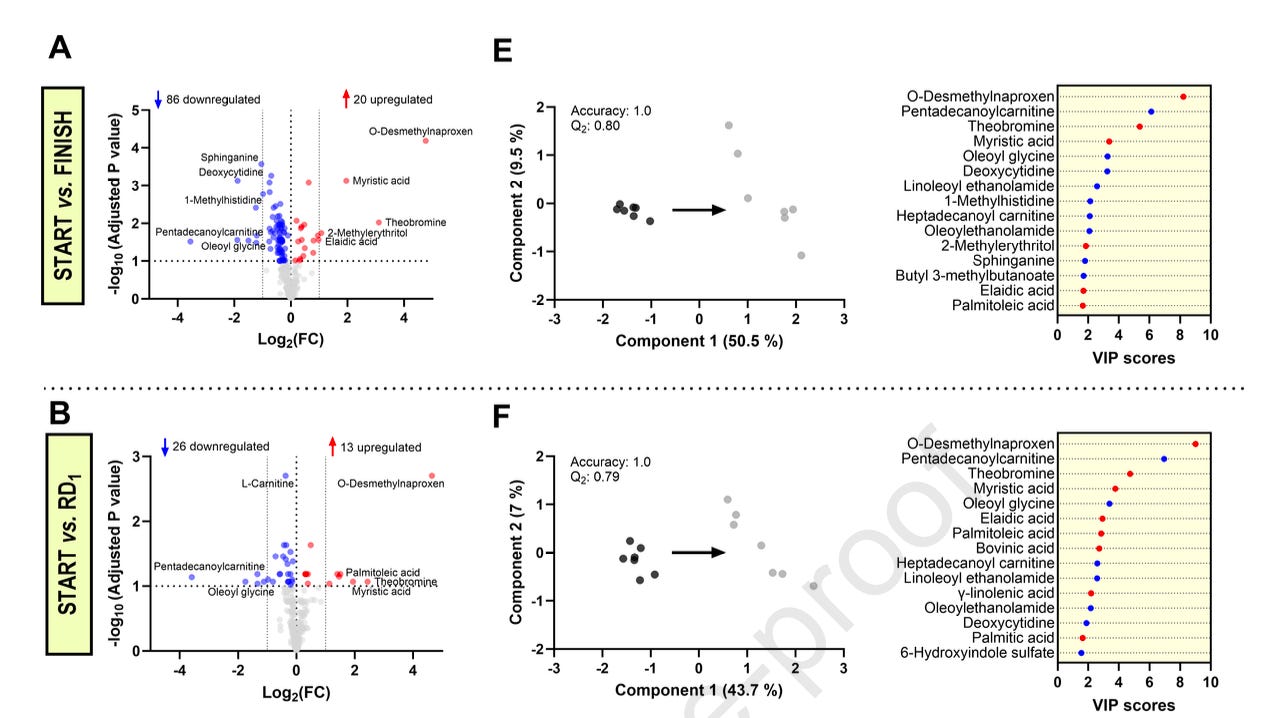

The Tour causes a broad depletion of metabolites

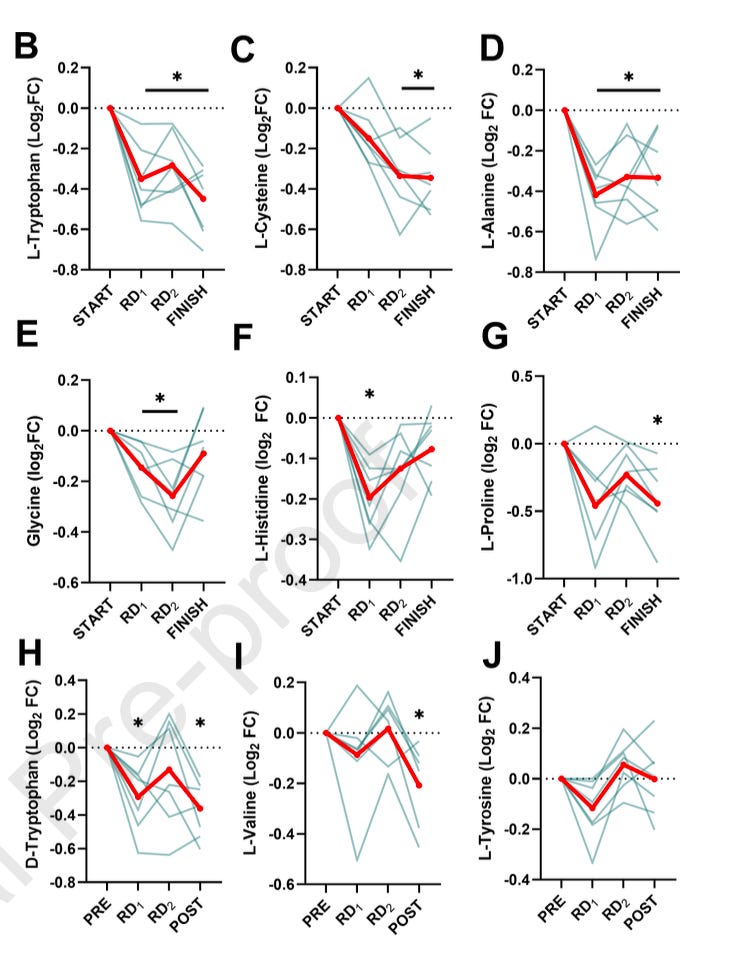

Across the Tour, 118 metabolites (43% of those measured) significantly changed, and the dominant direction of the change was down. When comparing the start of the race to the finish, far more metabolites decreased than increased, and the biggest change occurred from the start to the first rest day. The first 7–10 days were characterized by a huge metabolite shift with the general theme of utilization outpacing replenishment (hence why so many metabolites went down and not up).

This tells us that:

The body is most “dysregulated” at the initial shock of the Tour de France and

There’s somewhat of an “adaptation” after about a week of prolonged racing, likely when the body (somewhat) starts to drift back down (or more likely get body-slammed) into homeostasis.

So, what changed the most?

Two pathways stood out:

Beta-oxidation (the pathway through which we “burn fat”)

Glutathione metabolism (our body’s main antioxidant pathway)

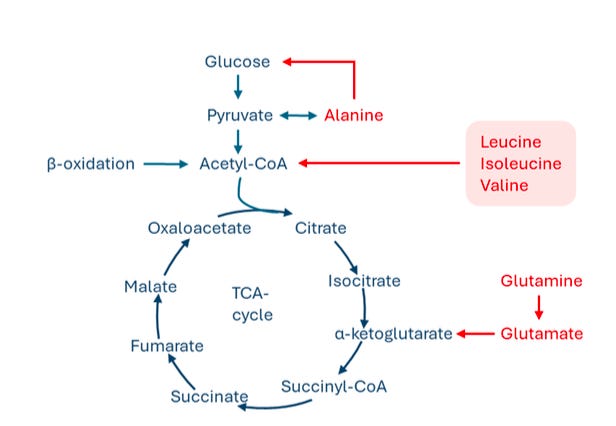

A large part of the signature was tied to fatty acid metabolism, in particular carnitine and acylcarnitine, which are part of the shuttle system that helps move fatty acids into the mitochondria to produce energy. Free L-carnitine and several medium- and long-chain acylcarnitines went down, while at the same time, intermediates of the Krebs cycle (aka the TCA cycle, our body’s main energy-production pathway) increased over time, indicating a heavy reliance on aerobic metabolism throughout the Tour (no surprise there).

Normally, a downregulated acylcarnitine pool could be interpreted as reduced fat oxidation. But the authors argue that the stability of the dominant pools (major fatty acids and the most abundant acylcarnitines), plus rising TCA intermediates, suggests fat oxidation was not globally reduced. Instead, the pattern looks like selective adaptations in transport/oxidation capacity—potentially reflecting increased tissue uptake of carnitine to sustain mitochondrial fatty acid transport under extreme demand.

They also outline plausible mechanisms for why L-carnitine and specific acylcarnitine pools might fall: reduced biosynthesis, reduced activity of transporters, or enhanced utilization.

One of the coolest details here was the selective depletion of saturated (but not unsaturated) fatty acids, which diverges from the “typical” response where unsaturated fats are preferentially oxidized during exercise. The authors propose a metabolic-efficiency explanation: saturated fat oxidation requires fewer steps to “burn” than unsaturated fats of the same chain length, potentially making it the “cheaper” substrate under conditions of metabolic overload (like the race).

The results also highlight cysteine as the most depleted semi-essential amino acid, showing a continuous decline across all cyclists. They connect this to increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). How’s this tied to glutathione? Remember that glutathione is the primary intracellular antioxidant. Because cysteine is the rate-limiting substrate for glutathione synthesis, progressive cysteine depletion may reflect heightened demand for glutathione production to buffer oxidative stress.

Enter a practical application for overtraining. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has been shown to improve glutathione status and endurance performance in fatigued states, and could plausibly help by supporting antioxidant capacity.

Intuitively, these two major shifts make a lot of sense if we simply think about the demands that the Tour de France imposes on the body.

While it involves a lot of intense cycling, most of the race involves steady state, aerobic riding, which places a huge stress on the body’s fat metabolism. At the same time, the demands of the event coupled with the need for recovery stress endogenous antioxidant systems (glutathione) so much that it simply cannot keep up. And these two systems were the main ones that stood out as being the most dysregulated after three weeks of racing.

What shows up as “overtraining biomarkers?”

The fatigue analysis is one of the most practically useful parts of the paper.

Researchers didn’t just measure metabolites, they asked if any of these track with how destroyed the athletes feel. The goal was to identify candidate blood-based biomarkers for training monitoring and detecting training imbalances.

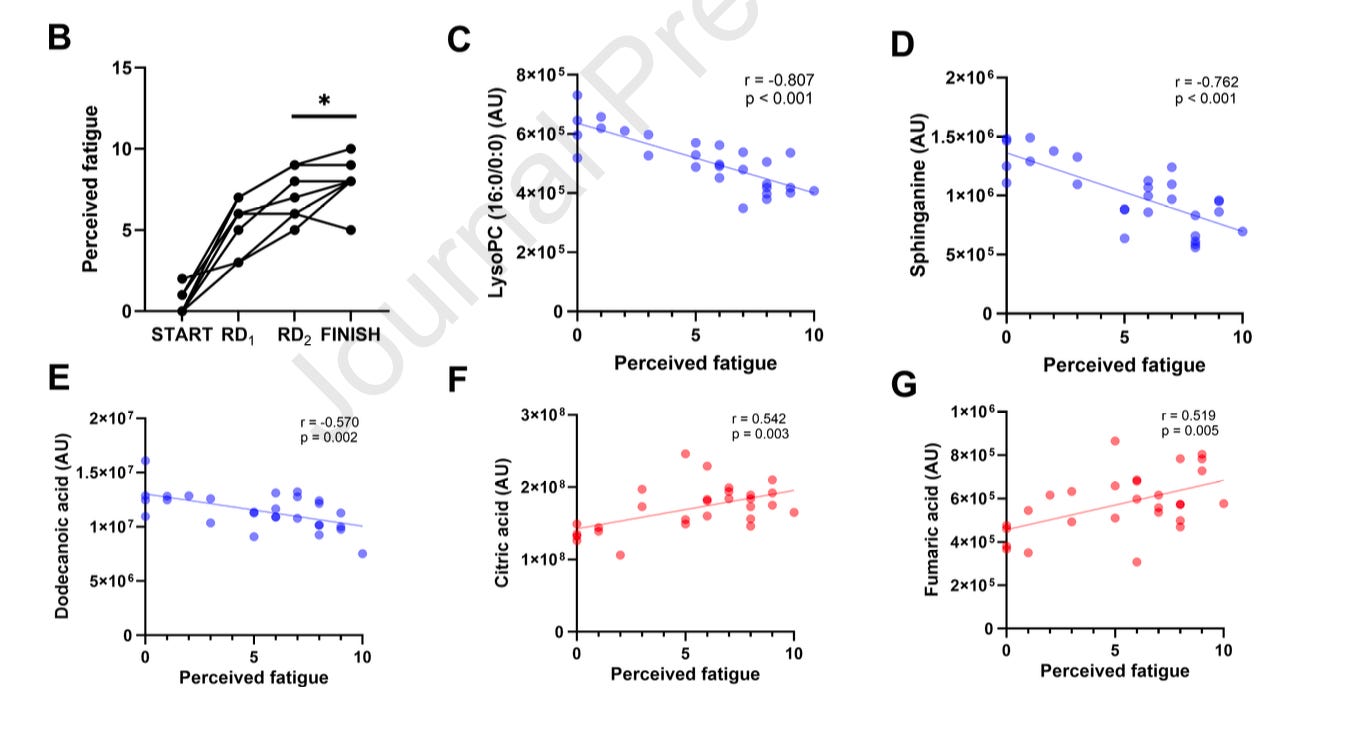

Cyclists rated perceived fatigue on a 0–10 scale at each blood draw, rising from 0.5 at the start to 5 at the first rest day, and reaching 8 by the finish.

Then they correlated fatigue with every metabolite, identifying 84 significant metabolite–fatigue correlations, and 77 were negative (fatigue up, metabolite down). These metabolites spanned lipids, fatty acids, and amino acids—and importantly, they note that most of these haven’t previously been linked to fatigue/overreaching, which is why they pitch them as “novel” biomarker candidates.

The strongest negative correlations were lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPC, a derivative of phosphatidylcholine) and sphinganine. Both sit in the world of cell membrane metabolism, prompting the authors to suggest that cell membrane dynamics may play a role in fatigue development.

Only seven metabolites were positively correlated with fatigue, including citrate and fumarate, consistent with increasing TCA cycle activity (more aerobic metabolism) alongside rising perceived fatigue. Makes sense to me.

Along with just being a truly interesting and one-of-a-kind study in an elite subpopulation of athletes, this paper provides a ranked list of candidate signals that move in lockstep with perceived fatigue under extreme real-world training load. These signals are tied to cell membrane biology, mitochondrial throughput, and a broader theme of metabolite depletion outpacing replenishment.

The authors position these as potential biomarkers for training monitoring—not “final answers,” but a set of hypotheses now testable in larger athlete cohorts and in settings where some athletes do tip into non-functional overreaching or overtraining syndrome.

Was the novel finding that three weeks of intense bike racing places an enormous stress on the human body? No, the novel finding was how, and how that expressed itself in the body’s metabolic signature.

Because most of us aren’t regularly measuring our blood for a detailed metabolomic analysis (I wish), we don’t really have a way of using biomarkers like these in our own training.

But that’s why I think the correlation with fatigue in this study is so potentially useful. What if it turns out that your perceived effort actually tracks quite nicely with these blood-based biomarkers? If that’s the case, our simple ratings of fatigue every day or throughout a training cycle may be all that we need to hint at whether we are veering into “overtraining territory.”

It’s a friendly reminder that in-depth analyses are fun, but how you feel is ultimately the only health and training metric that really matters. That’s true whether you’re a Tour de France cyclist or somebody like me who rides endless hours on a bike in my garage, going nowhere.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 20% off their order.

ProBio Nutrition—the all-in-one supplement that I use every single day—is offering 20% off. My preference is the tangy orange flavor, but they also sell an unflavored “smoothie booster” that’s great in a shake, smoothie, or juice.

Equip Foods makes some of the cleanest, best-tasting protein products around. I am absolutely obsessed with their Prime grass-fed protein bars (the peanut butter ones are to die for). Take up to 10% off site-wide and up to 35% off a subscription.

Great read as always! I've always said the same about this statement " If we want a model of excessive exercise (and diminished recovery), the Tour de France is it." Not just Tour de France, Il Giro, La Vuelta...I mean, what these guys do is not normal whatsoever! And yet...as you mentioned at the end of the post, feeling is still king in a way.

I think we're still all at sea with antioxidants. Clearly they have benefits but also can reduce training adaptations. This study suggests high dose NAC and presumably glycine could help TdF riders towards the end of the race but are they counter productive in training? What about for ordinary athletes? Other studies showed benefits in older people but not younger. All quite tricky.