Sleep and Cardiovascular Disease Part IV: Mechanisms Linking Short Sleep to Poor Heart Health

Why you should give your heart a rest.

Greetings!

Last week, I released part III of my blog series on sleep and cardiovascular disease. You can read that post using the link below.

If you missed parts I and or II, you can find links to those posts below.

To access those posts (and this one!), you’ll need to become a paid subscriber.

While my weekly Friday newsletter is and will remain free, more in depth posts like this are only available to paid supporters of my Substack.

To those who already support, thanks a million!

Here’s what to look forward to in the remaining parts of this series:

Part V: Exercise as a Strategy to Protect against the Negative Effects of Sleep Loss

A running theme throughout this series has been this: the shorter your sleep, the worse your health outcomes tend to be.

In part IV of this series, we’re going to explore the mechanisms that cause dysfunction and disease in people who don’t get enough sleep. While this isn’t an exhaustive list, research has given attention to three primary pathways that will be discussed: inflammation and oxidative stress, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and circadian rhythm disruption.

It’s important to explore mechanisms for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that it enhances our ability to develop potential treatments or interventions to prevent or reverse the health complications caused by insufficient sleep.

In theory, if we know the cause, we have the solution (yes, “sleep more” is priority number one).

In other ways, it’s interesting, if not necessary, to know what is going on in the body when we’re sleep deprived. How does this physiological state differ from that when we’re well-rested?

We’ve already mentioned endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness as potential causes of the increased cardiovascular disease risk associated with poor sleep, but now, we’re going to talk about what is leading to endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness.

While some of the evidence below is derived from association studies, a large portion is based on experimental data in humans and rodents.

Inflammation and Oxidative Stress 🦠🔥

Chronic, low-grade inflammation plays a role in several diseases, not just cardiovascular disease.

Acute inflammation serves a crucial role in our body by responding to infections and injury by helping us to adapt, heal, and grow more resilient. On the other hand, chronic inflammation is not good — it’s as if our body is constantly attacking itself. For this reason, inflammation can lead to a lot of issues and contributes to the development of cardiovascular and cardiometabolic diseases.1

Sleep duration (how many hours of sleep we get each night) is negatively associated with levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines — people with shorter sleep have higher more inflammation.2 Furthermore, experimental sleep restriction elevates levels of inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, TNF-α, Interferon-y, and C-reactive protein.34

Some studies have found that 29-40 hours of complete or total sleep deprivation increases inflammatory markers, but only after a day of recovery sleep,56 suggesting a delayed response to sleep loss. This is also a bit concerning, because it implies that even a night of recovery sleep isn’t enough to return you to normal after a bout of sleep deprivation.

High levels of inflammation promote adverse changes to blood vessel structure and function through multiple pathways, as shown below.

For example, inflammation increases arterial stiffness and reduces the elastic properties of our arteries.

Chronic inflammation is a major cause of the age-related increase in arterial stiffness. This occurs through an increase in growth factors and collagen production in blood vessels, making them stiffer and promoting atherosclerosis.

High levels of inflammation cause structural remodeling of blood vessels, leading to diminished cardiovascular health and impaired endothelial function.

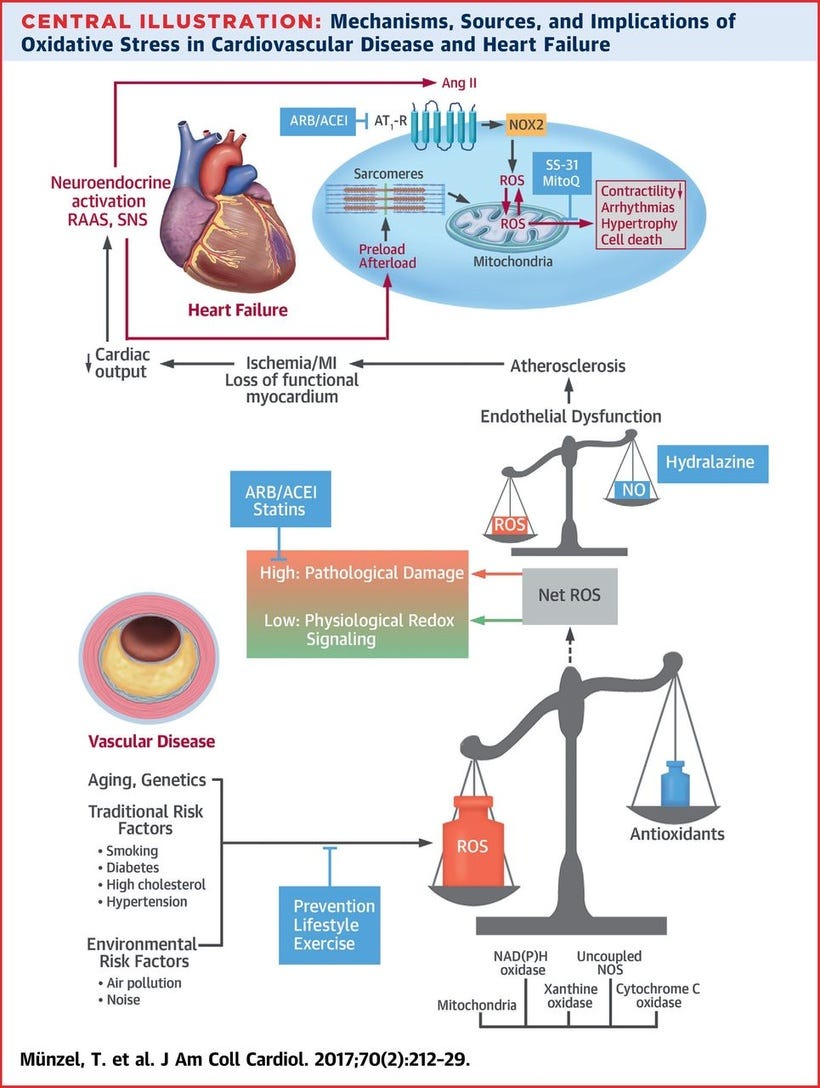

Oxidative stress is generally classified as an imbalance of antioxidants and pro-oxidants in the body. Oxidants, also known as reactive oxygen species (ROS), are highly-reactive molecules that cause cellular damage among other effects (though they also have important and necessary signaling functions).

Oxidative stress can be increased by inflammation, but ROS can also lead to inflammatory responses in the body — perpetuating a vicious cycle.

Similar to inflammation, biomarkers of oxidative stress are elevated in people with a short sleep duration.78

ROS are also enemies of blood vessels. Thus, high and uncontrolled levels of ROS in response to insufficient sleep mediate vascular dysfunction — they do this by reducing levels of nitric oxide (NO) which we need to help blood vessels relax.

In fact, NO bioavailability is reduced after sleep deprivation, and people with a short sleep duration have been shown to have lower levels of NO than people who get a normal amount of sleep.9 Reduced levels of NO likely explain a greater risk for heart disease in these people — a loss of NO bioavailability is one factor that plays a role in the development of cardiovascular disease.

Sleep deprivation also causes us to produce fewer antioxidants — which our body uses to protect against the negative effects of ROS.

Autonomic Nervous System Dysregulation 🧠

We have two branches of our autonomic nervous system: the sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic (PNS) systems.

In general, sympathetic activity (known as our “fight and flight” response) is associated with an increase in heart rate, elevated blood pressure, and endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness.