Sleep and Cardiovascular Disease Part V: The Protective Effects of Exercise against Insufficient Sleep

Can you "outrun" a lack of shuteye?

Greetings!

Last week, I released part IV of my blog series on sleep and cardiovascular disease. You can read that post using the link below.

If you missed parts I, II, or III, you can find links to those posts below.

To access those posts (and this one!), you’ll need to become a paid subscriber.

While my weekly Friday newsletter is and will remain free, more in depth posts like this are only available to paid supporters of my Substack.

To those who already support, thanks a million!

We all need about 6—9 hours of sleep each night for optimal health.

This recommendation is supported by numerous health organizations and backed by epidemiological data showing that a short sleep duration (less than 6 hours per night) is associated with a greater risk for a variety of adverse health outcomes — most of which you’ll be familiar with if you’ve read previous posts in this series.

But, no surprise, about 50% of adults don’t get enough sleep. Even when we strive to do so, life gets in the way — whether it be family or work events or the all-too-common late-night social media scrolling, so called “sleep procrastination”.

Losing a few hours of sleep here and there isn’t anything to stress about, but it is interesting to think about potential ways to mitigate the harms of sleep deprivation when it does occur.

What strategies might be able to prevent the effects of insufficient sleep on cognitive performance, memory, cardiovascular function, athletic performance, mitochondrial function, or metabolism?

Several studies have investigated this question: Can exercise protect you from the acute effects of insufficient sleep?

Below, I’ll summarize handful of studies that show some pretty interesting data suggesting that the answer to this question might be a resounding “yes”.

Heart and blood vessels

A study published in 2017 found that getting fitter was effective for preventing the negative effects of sleep on endothelial function. Performing 7 weeks of combined high-intensity interval training and continuous endurance training prevented endothelial dysfunction after 40 hours of sleep deprivation — whereas before training, endothelial dysfunction occurred.1

This effect was attributed to a reduced acute inflammatory response after exercise training. Inflammatory cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α were lower after sleep deprivation that was preceded by exercise training compared to sleep deprivation without exercise, when inflammation increased. In the same study, arterial stiffness was also increased after 40 hours of sleep deprivation but was prevented when preceded by exercise training. These findings are neat because they suggest that fitness has a protective effect against the stress of sleep deprivation — at least in the short term.

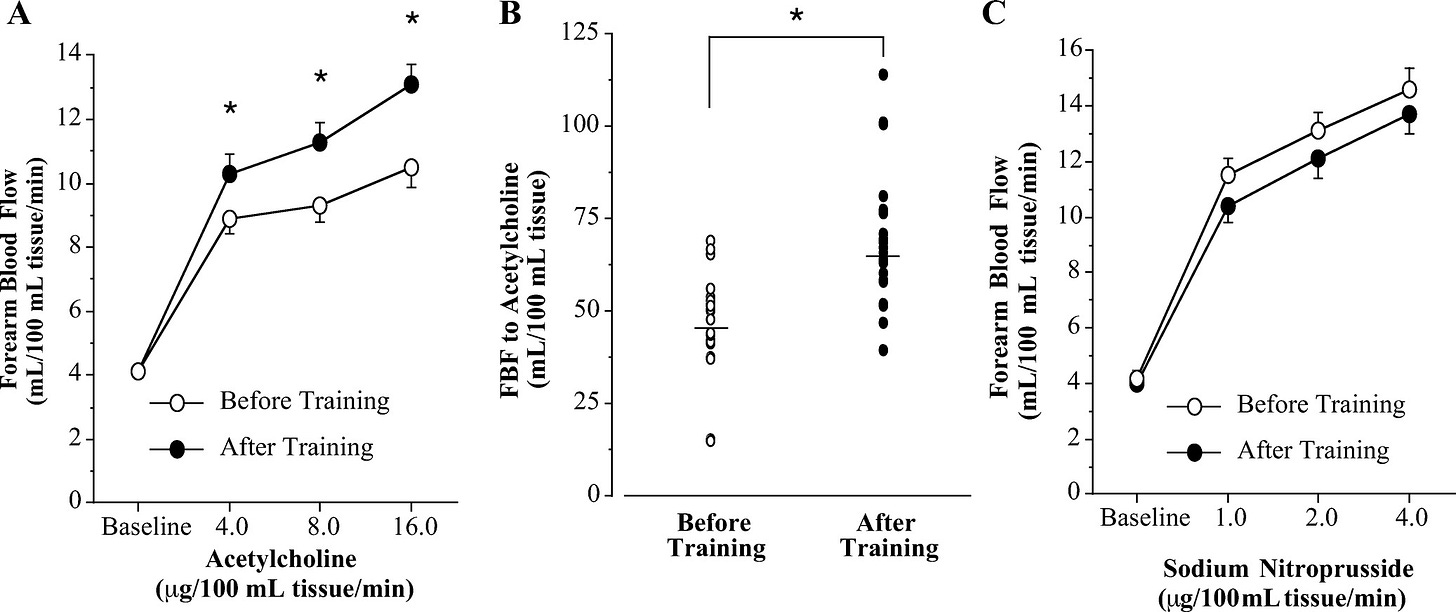

This conclusion is supported by more a more recent cross-sectional study from 2021. Two groups of adults were compared — those with a habitual short sleep duration (6.2 hours/night) and a habitual normal sleep duration (7.4 hours/night). The short sleepers — no surprise — had worse endothelial function. However, after 3 months of aerobic exercise training, endothelial function increased in the short sleepers despite no change in their sleep duration.2

Metabolism and protein synthesis

After sleep deprivation, our metabolism is haywire and glucose regulation is impaired — we’re basically diabetic.

Several investigations have provided evidence that exercise may represent an effective countermeasure against the pathological effects of sleep deprivation on measures of health and performance — and fitness might protect us in this regard.