Using Periodized Nutrition to Optimize Metabolic Adaptations to Exercise

Fuel for the work required.

Athletes have always been obsessed with how to fuel peak performance — what types of food and drink will produce the fastest running time, highest power output, and largest competitive edge?

This isn’t something new to modern-day athletics either. Ancient Greeks and Romans experimented with diet and training, although with a bit less scientific insight than we have today. Indeed, there are several accounts of what comprised the diets of ancient athletes. Some were said to have “consumed a diet which was mainly based on cereal (carbohydrate), olive oil (lipid/fat) and wine.” Their main source of protein intake may have come from cheese, since milk could not be stored well in a warm climate.

Charmis of Sparta is said to have trained on dried figs, “the tradition would seem to indicate that as a sprinter he found the extra sugar in fruit useful.”1 Additional accounts also include figs as well as moist cheeses and wheat as part of the ancient athlete diet. But this isn’t to say all athletes took a mostly plant-based approach. Indeed, Dromeus of Stymphalos is said to have first included meat as part of his training diet. Until then, “the food for athletes was cheese fresh out of the basket.” Perhaps the first iteration of the carnivore diet?

Not only did athletes concern themselves with what to eat to improve performance, but also with what not to eat to maintain the ideal athletic physique. History tells of how “...they kept off bread, realizing the dangers of too much starch” and that “...if they wished to succeed as athletes, they must observe restraint in their eating and avoid rich confectionery.” Did these ancients also realize the limits to “outrunning a bad diet” or perhaps even experiment at times with a low-carbohydrate approach to nutrition?

While it’s interesting to look back on the dietary practices of athletes, we now know much more about sports nutrition thanks to the practices of athletes with evidence-backed support from science and rigorous laboratory and field testing. This has led to a renaissance in how we think about the proper ways to fuel exercise.

Traditional approaches to fueling exercise

For athletes in endurance and team sports (i.e. events lasting 60-90 minutes or more), the proper fueling strategy has prioritized consuming adequate carbohydrate to sustain performance, with the goal of maximizing glycogen availability, meeting the energetic demands of the sport, and reducing or prolonging fatigue development. The basis for these recommendations is founded in bioenergetics. During high-intensity and prolonged exercise, our body breaks down glucose and glycogen to produce ATP, so having enough fuel on board is crucial, as is the provision of exogenous sources (CHO drinks or energy bars, for example) to keep fuel levels high, especially in events lasting >90 minutes.

For recreational athletes, the recommended carbohydrate intake is around 3-5 grams per kilogram of body weight per day. If you weigh 70kg, this means consuming about 210-350 grams of carbohydrate per day. For athletes training at a high volume, the recommended intake is around 5-8 grams/kg per day. The strategy of “carbohydrate loading” is also advocated prior to long-duration events or competition. This involves consuming anywhere from 10-12 grams/kg of carbohydrate in the 24-48 hours leading up to exercise.

A recent position stand by the International Society for Sports Nutrition (ISSN) doesn’t shy away from a carb-centric approach to fueling exercise, stating that “...the need for optimal carbohydrates in the diet for those athletes seeking maximal physical performance is unquestioned. Daily consumption of appropriate amounts of carbohydrate is the first and most important step for any competing athlete.”2

Though carbs are hailed as king or queen, there has been a recent paradigm shift in how athletes approach fueling their day-to-day training. Many claim that a high-carb approach to sport may have unintended and perhaps deleterious side effects on long-term metabolic health. Carb-loading and mid-race gels might help performance, but at what cost?

While there isn’t much evidence to suggest athletes are necessarily being harmed by their nutrition practices, the discussion on low-carb diets for sport is increasing in popularity due to athletes including ultrarunner Zach Bitter and the research undertaken by individuals such as Drs. Jeff Volek and Stephen Phinney — who have long been studying the effects of low-carbohydrate diets on health and performance in athletic and non-athletic populations.

There is a growing segment of athletes who wish to optimize not only their athletic performance, but also their metabolic health. This means modifying the traditional athletic diet and using strategic, rather than indiscriminate, leveraging of carbohydrate consumption into their training regimen.

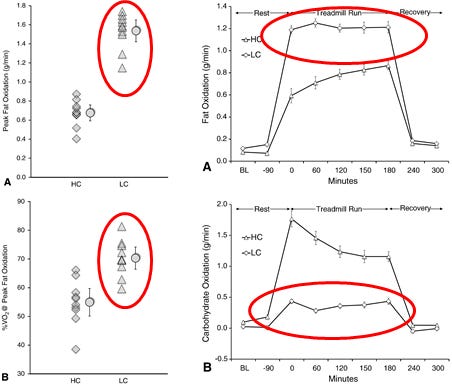

In theory, there are several benefits to a low-carbohydrate diet for athletes. For one, at lower exercise intensities, fat can be used as a fuel and provide necessary substrate for energy production. One characteristic of low-carb athletes is that they are drastically better at burning fat during exercise than athletes on a high-carbohydrate diet, and even able to burn fat at a relatively higher exercise intensity (70% VO2 max vs. 55% VO2 max).3 This enhanced fat-burning capacity also may have a glycogen-sparing effect and reduce the need for athletes to fuel during exercise with carbohydrate-based gels and sports drinks.

Other potential benefits include better metabolic health (low-carb diets may improve insulin sensitivity and blood glucose control), enhanced recovery, and improved body composition, all of which have been reported (and shown) to occur in athletes following a low-carb diet for various amounts of time.

However, when it comes to performance, the data are not in favor of adopting a low-carbohydrate approach. Indeed, several studies have shown evidence that when athletes adopt a low-carb/ketogenic diet during training, they fail to improve their time-trial performance and their exercise economy decreases — despite significant increases in their ability to burn fat during exercise.4

In a recent review article, noted sports performance scientist Dr. Louise Burke summarizes the current knowledge on low-carb diets for performance noting that overall, the studies suggest that performance at moderate exercise intensities is preserved (i.e. not enhanced or reduced) following adaptation to a low-carb diet. However, there exists a high individual variability in studies, with no evidence of improved performance and a potential reduction in high-intensity performance due to reduced exercise economy. Low-carb diets can likely support the needs of lower power outputs or slower finishing times, and may yield benefits for athletes when used for body fat loss in overweight athletes or those involved in weight-conscious disciplines.

Low-carb diets may not be the optimal route to peak performance, but high-carbohydrate diets may not be ideal for long-term metabolic health. How does one reconcile these divergent outcomes and, if the goal is optimizing performance and health, how might one go about designing a training and nutrition regimen?

Periodized nutrition

The concept of periodizing nutrition has become a popular practice among athletes and could similarly be used by anyone undertaking an exercise routine to improve physical performance and health.