What Science Says about Fasted Exercise

Are there benefits to working out "on empty"?

Intermittent fasting (IF), while an ancient practice, has gained newfound popularity for the supposed benefits it could have for weight loss, metabolic health, and even longevity; despite some studies showing it’s not much better than simply reducing ones caloric intake.

An area where fasting has also gained attention is in relation to exercise. Many health and performance experts advocate fasted exercise. In my opinion, fasted exercise can have a place in most training regimens, if used strategically, though it may not be optimal for high performance.

Fasting physiology

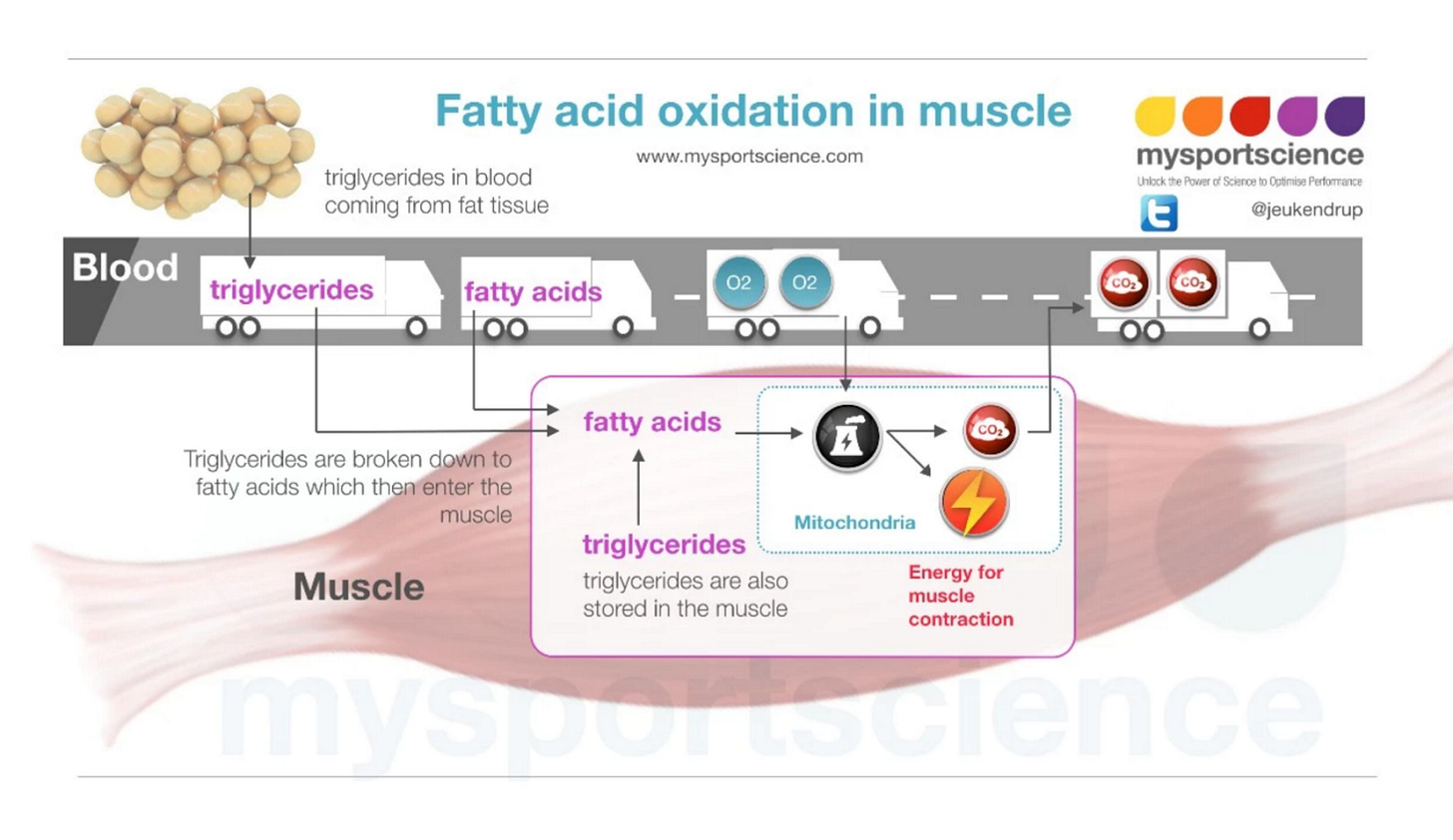

When you’re fasting, blood glucose, glycogen, and insulin decrease, and our body upregulates enzymes and pathways that oxidize fatty acids to produce energy, putting us into a “fat burning” state. This is why some intermittent fasting and time-restricted feeding (TRF) studies find that this dietary regimen may be good for weight loss and improvements in body composition (though not all find this benefit).

Regarding fasted exercise, the theory is that working out while fasted should enhance your ability to burn fat and increase the actual amount of fat you burn during exercise— leading to metabolic adaptations and an improved body composition (more lean mass and less fat mass).

There are also other potential benefits of fasted exercise including improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, increased mitochondrial adaptations, and exercise-induced ketone production.

The caveat here is that, as anyone who works out knows, food is a source of energy, and a light pre-workout snack is often going to be beneficial for overall mood and performance. So fasted exercise is a “tradeoff” of sorts, in which we sacrifice performance for supposed metabolic benefits.

This is why I say that a strategic use of fasted exercise could be beneficial.

Lower intensity training sessions (an easy run lasting 60 minutes or less) could be done in the fasted state, since the energy needed for this type of effort and duration could be provided through aerobic metabolism via fat oxidation. More high intensity or prolonged sessions might benefit from a bit of pre-workout carbohydrates.

Unfortunately, there hasn’t been much research on whether exercising while fasted is actually superior when it comes to health outcomes.

I’ll note here that there is unequivocal evidence (published and anecdotal) that fasted exercise is NOT better for exercise performance. In no way will you run faster or lift heavier in the fasted vs. fed state. This is well known. What we are talking about here is whether certain beneficial adaptations might occur during fasted exercise that, in the long term, will benefit health.

There are several different realms where fasted exercise has been investigated including body composition, performance outcomes, and what we will generally refer to as metabolic/mitochondrial adaptations.

Body composition

A study1 conducted in 20 healthy female participants found that fasted exercise was not any better than fed exercise for reducing body weight and total fat mass during a diet designed for weight loss (a hypocaloric diet).

The training in this study was moderate-intensity aerobic exercise for 1 hour/day, 3 time per week. The fasting group performed training sessions after an overnight fast, and the fed group was given a pre-workout nutrition shake that contained 40g of carbohydrates, 20g of protein, and 0.5g of fat. The fasted group consumed the shake immediately after each training session.

As you can see in the table above, both groups lost weight and fat mass during the study, but there were no differences between fed and fasted groups for the amount of weight and fat lost during the study. In other words: fed and fasted exercise were equally effective.

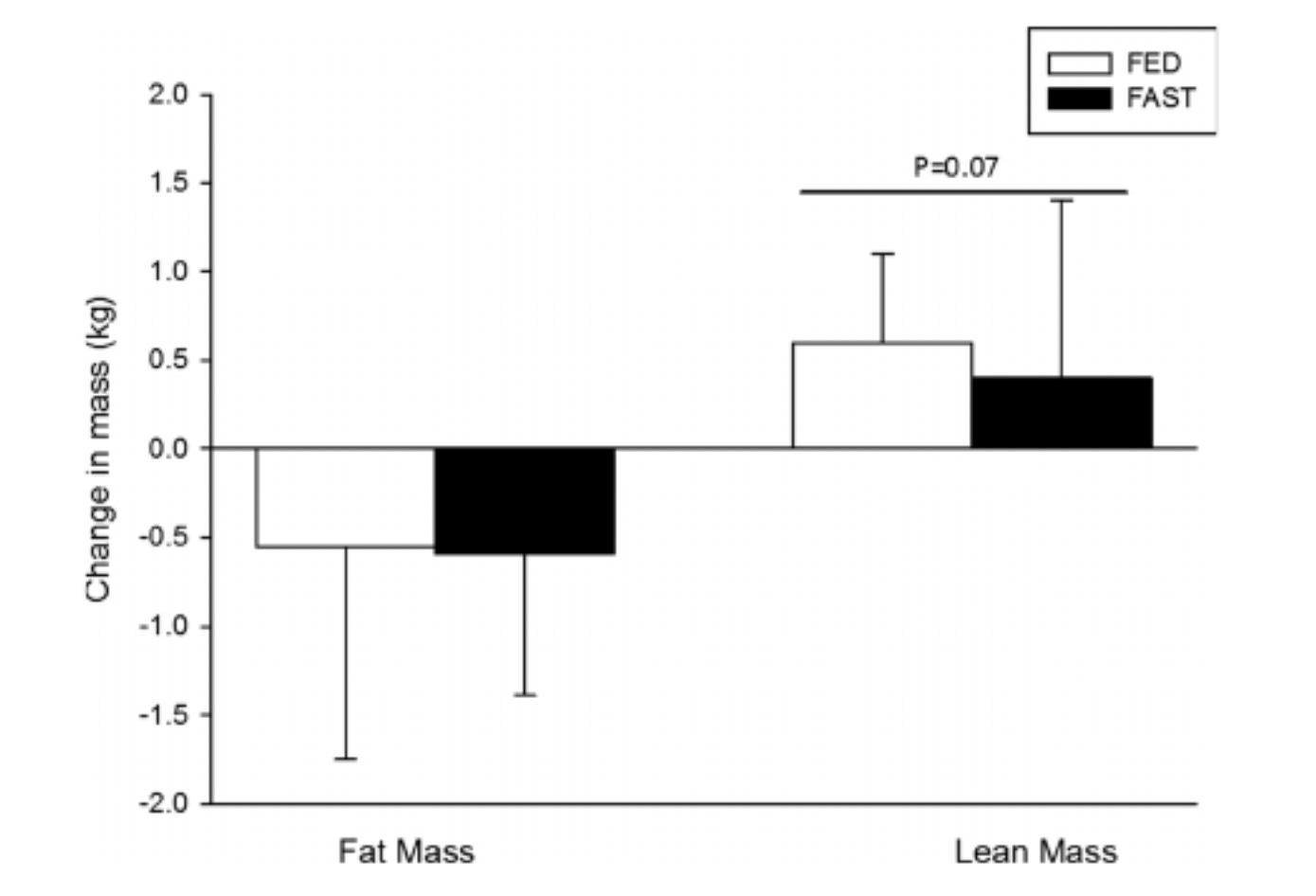

Another study2 compared the effects of fasted vs. fed high-intensity interval training (HIIT) for six week on body weight, fat mass and body fat %, and lean mass in overweight women. They performed 3 sessions per week of HIIT for 6 weeks. The fasted group completed all sessions after an overnight fast, and the fed group consumed a pre-exercise meal of an energy bar, yogurt, and orange juice (the fasted group consumed this same meal post-exercise).

Again — differences between groups were non-existent. Both groups had reduced body fat % and increased lean body mass after the training, but no superior effects of fasted exercise were observed.

Performance

As I mentioned earlier, there is hardly a need to debate whether fasted exercise actually improves exercise performance. Exogenous carbohydrates and fat are major fuel sources during exercise, and providing them via pre-workout feeding will, in most cases, enhance performance.

To summarize performance outcomes, we need to look no further than a meta-analysis published in 20183 that evaluated all of the studies comparing fed vs. fasted exercise on outcomes of exercise performance.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Physiologically Speaking to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.