Will Humans Live to 150? Not in Our Lifetime

The “radical” idea of radical life extension.

If you could live to be 150 years old, would you?

One’s answer to this question inevitably hinges on a few things: Whether they’ll arrive there in good health and whether they’ll get to enjoy longevity with friends and family whom they love. What’s the allure of immorality spent in isolation and despair?

I, for one, would gladly jump at any opportunity that gave me a chance of nearly doubling the average human lifespan. Why not? (Given the abovementioned conditions, of course).

Some science fads pass, but humanity has always been captivated by the idea of extending life. Today, this fascination is reaching new heights, as science meets ambition to push the limits of human lifespan. The “longevity movement” is fueled by unprecedented advancements in biotechnology, gene therapy, and anti-aging research. Those who lead the movement talk excitedly about the prospect of defeating death.

But are we too excited?

At the center of this excitement is a group of entrepreneurs and scientists who are actively investing in and experimenting with these emerging technologies. Bryan Johnson, for example, has garnered headlines for his ambitious and highly publicized attempt to reverse his biological age. Through his company Blueprint, Johnson spends millions each year on rigorous anti-aging regimens, to keep his body as youthful as possible with fasting, exercise, supplements, and other nontraditional approaches like blood transfusions from his son.

This optimism is shared by those who believe we are approaching a critical juncture—where medical advancements will soon allow humans to live far longer than ever before, perhaps 150 years or more. For many, this prospect is enticing because of the possibility of additional years and the promise of maintaining youth and health deep into old age.

Few want to live long without the option of also living well. In a world where aging is often associated with decline, frailty, and disease, the hope of extending life while staying healthy (e.g., maintaining healthspan) is enticing.

But while the enthusiasm is palpable, it also raises fundamental questions: How far can science realistically extend the human lifespan? And even if we can live to 150, should we? As researchers make strides in understanding the biology of aging, these questions will continue to shape the longevity debate.

Longevity Escape Velocity

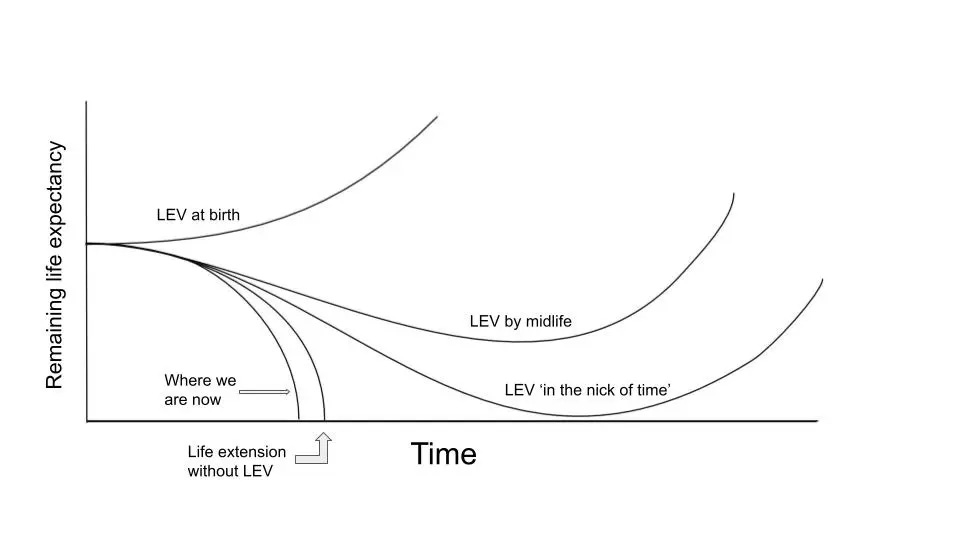

Critical to the idea of extending human lifespan is the concept of longevity escape velocity (LEV). LEV suggests there could be a point at which advances in medicine and biotechnology can extend human life faster than we age. In other words, if we can extend life by one year or more for every year that passes, we might be able to achieve a form of “escape velocity” where aging and death are postponed indefinitely.

The idea was popularized by Aubrey de Grey and others in the life extension field, who argue that ongoing advancements in regenerative medicine, gene therapies, and anti-aging interventions could allow us to keep pushing the boundaries of human lifespan. The ultimate hope of those who believe in LEV is that humans could theoretically live to 150 years or beyond, provided that medical advances outpace the aging process.

There are two key phases to achieving LEV:

Initially, life expectancy might increase by a few months or years for every decade due to advancements in treatments for age-related diseases or regenerative therapies. As medical technology improves, those gains will accumulate until the rate at which we can repair and reverse the damage caused by aging equals or exceeds the rate at which we age.

Once LEV is achieved, each year of research and development in the field of aging will buy us more time, pushing back the limits of human lifespan. Theoretically, this could mean people living to 150 years or more if successive breakthroughs continue to improve treatments for aging and age-related diseases.

Some scientists think we’ll achieve LEV in the next few decades, meaning that children being born today might have the shot of living to 150 years or more.

LEV and Radical Life Extension

Radical life extension and LEV are intertwined—both suggest a future where humans can live significantly longer lives than the current norm of 80–90 years. However, radical life extension focuses on whether significant, sustained gains in life expectancy (e.g., 0.3 years per year) are feasible based on current trends and medical advancements.

Most researchers in the field conclude that significant life extension, particularly living to 150 years or more, is unlikely without breakthroughs that can dramatically slow or reverse the biological aging process. This is where LEV comes into play. For people to live to 150 or beyond, LEV would have to be reached. That doesn’t seem to be happening anytime soon.

What’s holding us back?

Barriers to Longevity Escape Velocity

Based on our current understanding, LEV is being limited by a few things:

Biological aging: Much of the increase in life expectancy over the past century has come from reducing early deaths (infant mortality, infectious diseases) and improving health in mid-life (e.g., heart disease, cancer treatments). However, slowing the aging process itself, especially in advanced old age, has proven far more difficult.

Compression of mortality: As life expectancy has increased, deaths have become more compressed within a narrower age range (around 70–90 years). This means most people live long lives but tend to die in a similar age window. To break through this compression and extend life expectancy to 150 years or more, we would need to drastically reduce death rates in extreme old age—a challenge that current medical science has not yet overcome.

Limits to medical intervention: Current medical advancements primarily focus on treating age-related diseases as they arise, rather than preventing the underlying causes of aging. LEV would require a shift from managing diseases to preventing or reversing the aging process at a cellular and molecular level (that’s what Bryan Johnson and others are attempting to do).

How Do We Reach LEV?

LEV would likely rely heavily on breakthroughs in regenerative medicine, where damaged tissues and organs could be repaired or replaced, and cellular damage could be reversed. This is an ongoing area of research.

We could also leverage gene therapy and rejuvenation to find and develop interventions that can “turn back the clock” on aging cells and target the hallmarks of aging. For example, therapies targeting senescent cells (cells that no longer divide and contribute to aging or so-called “zombie cells”) or improving telomere length (the protective ends of chromosomes that shorten with age) are seen as potential avenues toward slowing aging.

Then there’s the repurposing of already developed compounds. Drugs like metformin, rapamycin, and newer compounds are being studied for their potential to slow the aging processes and extend healthy lifespan. The National Institute on Aging’s Interventions Testing Program (ITP) was developed for this purpose.

Where Are We Now?

While advances in medicine have increased life expectancy in high-income nations, the pace of increase has slowed dramatically since the 1990s. Additionally, without breakthroughs in the fundamental biology of aging, it will be very difficult to push the limits of human lifespan.

Proponents of LEV are more optimistic, believing that ongoing research in biotechnology, regenerative medicine, and anti-aging therapies will lead to the breakthroughs needed to achieve longevity escape velocity within a few decades. They envision a future where humans might routinely live to 150 years or more, with many people achieving biological immortality—where aging is no longer the dominant factor leading to death.

I’m not sure who’s correct, but the current evidence seems to suggest that the longevity skeptics are closer to the truth. That's based on evidence presented in a new study on life expectancy trends that provides insight into the possibility of radical life extension in our lifetime.

Radical Life Extension

Radical life extension is an increase in life expectancy at birth by 0.3 years annually or about three years per decade. This rate of increase was observed during certain periods of the twentieth century, a time when significant public health measures and medical advances were being implemented.