Physiology Friday #222: High-intensity Exercise Reduces Senescent “Pro-aging” Cells

But hold the ibuprofen.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter including Examine.com and my book “VO2 Max Essentials” can be found at the end of the post!

“Inflammation.”

It’s the word we all fear. The thing we’re all told to avoid because it contributes to a myriad of diseases and ailments. The process that causes aging and reduces lifespan.

This is true when applied to chronic inflammation, but not acute inflammation.

Rather, acute inflammation is a necessary response of our body to insults and injury. Without it, we don’t heal.

Inflammation is also intricately tied to exercise. During exercise, our body mounts an acute inflammatory response, releasing all sorts of cytokines, macrophages, and other molecules throughout the circulation. This makes sense — exercise is an incredible stress and leads to a considerable amount of muscle damage (which is intensity and duration-dependent). Inflammatory cells are recruited to repair the damage.

The thing with exercise is that it also exerts an anti-inflammatory effect in the proceeding hours to days. With exercise training, our body up regulates antioxidant and anti-inflammatory enzymes that lead to better health, reduced chronic inflammation, and less cellular stress.

The (anti)inflammatory effects of exercise may also contribute to its benefits for aging.

Specifically, inflammation and oxidative stress can cause the buildup of senescent cells in the body. Also known as “zombie cells”, senescent cells are cells that have stopped doing their normal job and are sort of just “hanging around” causing inflammation and other sorts of harm. When senescent cells lie around and accumulate, they promote. chronic inflammation through something known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype or SASP.

The accumulation of senescent cells is actually one of the “hallmarks of aging.” In short, you want to avoid accumulating senescent cells and/or get rid of the senescent cells you’ve accumulated if you hope to avoid disease and life a long, healthy life.

Exercise seems to be one way to do this, but the evidence in humans is limited. Furthermore, it’s unknown if exercise intensity matters for these benefits and if certain processes (like inflammation) are required for the effects to occur.

All of these questions were investigated in a new study published in the journal Aging.1

A total of 12 men between 20 and 26 years old who were not regular exercisers participated in the study. The participants completed two exercise conditions in a random order with a 3-week washout period in between.

In one condition, the participants performed a session of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and ingested a placebo capsule

In the other condition, the participants performed a session of HIIT and ingested 400 mg of Ibuprofen 2 hours before and 3 and 8 hours after exercise (for a total daily dose of 1200 mg)

Here’s the HIIT protocol they performed on a stationary cycle: a 3-minute warmup at 50 Watts followed by 20 seconds at 120% of their maximal power output and 20 seconds of rest, repeated 15 times (for a total of about 10 minutes).

For reference, the participants averaged 233 Watts during the HIIT sessions.

Before, 3 hours after, and 24 hours after exercise, the participants provided a muscle biopsy from their leg (vastus lateralis) which was then used to determine the levels of gene expression for the primary outcomes:

- p16INK4a — a marker of cell senescence

- CD11b — a marker of immune cell infiltration (inflammation)

Results

In the placebo condition, p16INK4a levels decreased by 82% 3 hours after exercise and by 62% 24 hours after exercise when compared to baseline levels, indicating that high-intensity exercise reduces cell senescence markers (that’s a good thing).

In the ibuprofen condition, p16INK4a levels also decreased 3 hours and 24 hours after exercise. However, p16INK4a levels weren’t as low as the placebo condition at 3 hours, though they were similar at 24 hours.

Things get interesting when we take a look at the individual participants’ responses to exercise. Those with high levels of senolytic markers before exercise experienced a major decrease in markers of cell senescence in the placebo condition. Something similar was observed in the ibuprofen condition, but it’s odd to see that a few participants saw an increase in senolytic markers.

Regarding inflammation, both high-intensity exercise + placebo and high-intensity exercise + ibuprofen led to lower levels of inflammatory markers at 3 hours (87% and 66%, respectively) and 24 hours (80% and 73%, respectively) after exercise, Of note, exercise + ibuprofen failed to significantly reduce inflammation 3 hours after exercise when compared to pre-exercise levels.

Just like with the cell senescence markers, inflammatory markers declined drastically among the participants with higher baseline levels of inflammation.

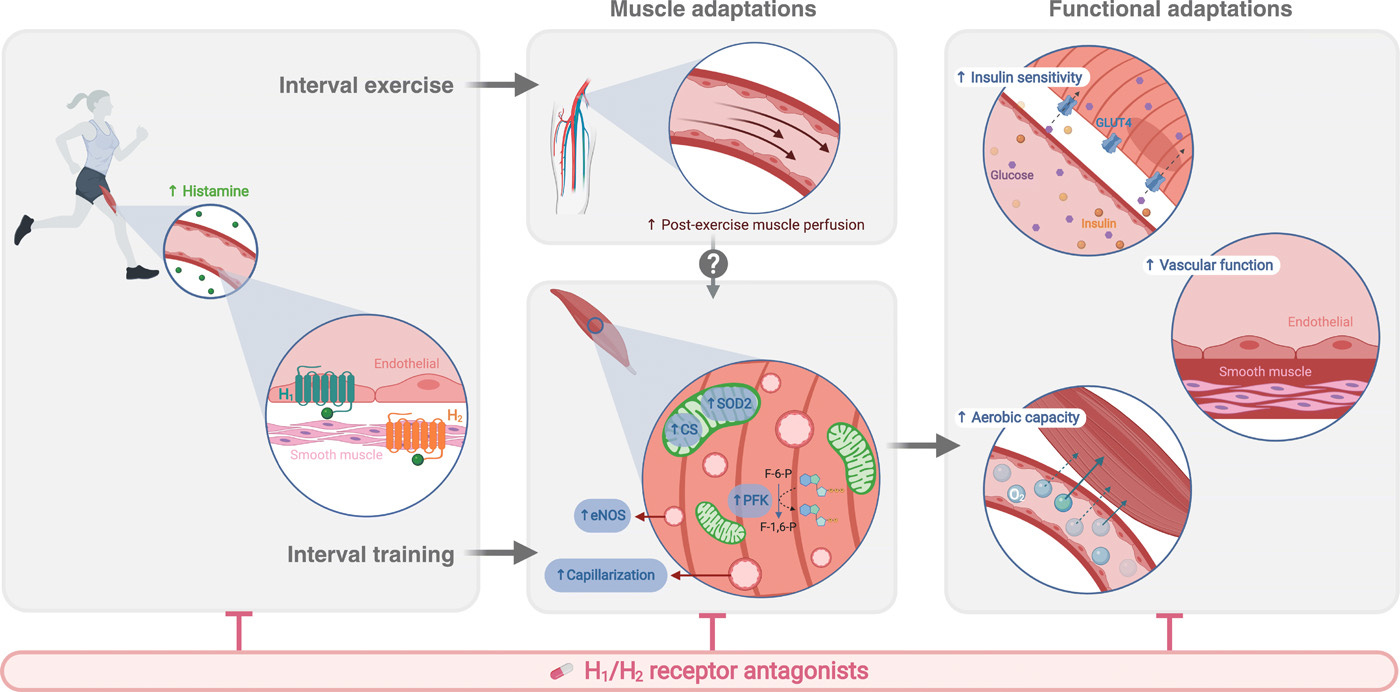

A few years ago, it was shown that histamines were essential transducers of the benefits of exercise — taking an antihistamine blunted the effects of exercise on vascular function, blood glucose control, and exercise capacity.

More recently, it’s become abundantly clear that immersing yourself in cold water after exercise will at least mitigate some of your gains in muscle hypertrophy and strength — likely through cold’s anti-inflammatory effects.

It has also long been known that supplementing with antioxidants blunts adaptations to exercise, an ironic truth since antioxidant supplementation was all the rage for a while, especially among the exercise fanatics and the health-conscious.

Based on the findings of this study and some of the evidence I’ve just listed, it’s clear that we want to avoid anything “anti-inflammatory” in the periods before and after exercise at all costs.

Forget special recovery gadgets, ditch the recovery supplement, and for the love of god please avoid taking an ice bath or taking an NSAID after your workout. Let your body’s natural course of exercise-induced inflammation run its course. It’s an integral part of how we get bigger, faster, and stronger.

And in the case of this study, it’s also essential for our body’s ability to clear our senescent cells that contribute to the process of aging.

Let’s talk about those senescent cells for a moment. The fact that exercise reduces senescent cell markers indicates that this may be one of the ways by which exercise exerts its “anti-aging” effects.

Importantly, intensity may be a crucial determinant of whether exercise clears our senescent cells. The same group conducting the current study has previously published evidence that high-intensity exercise — but not moderate-intensity exercise — reduces senescent cell markers 24 hours post-exercise.

This is likely because high-intensity exercise elicits a greater acute inflammatory response and thus, a larger anti-inflammatory response in the hours to days after exercise.

Let’s be clear: you’re not going to completely erase the benefits of your workout if you take a painkiller or drink an antioxidant-rich smoothie — we’re probably taking very minuscule differences here, especially over the long term. But in any case, getting the most from your workout means letting inflammation do its thing.

Often, the best recovery strategy is to do nothing at all.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

Is there any view of what is best for stress in general? HIT or zone 2 type exercise? Which removes cortisol better or is better for stress overall?

Do you really think that the bodies of the participants cleared out the senescent cells that fast? I honestly highly doubt that. And why would the marker then rise again that steeply in 24 h? Are the cells back to being senescent again after a short period of normal function? Or have the participants "restocked" a fixed pool of senescent cells?

I rather think that this is a typical marker/outcome problem. Further, there are several functions to this protein (see for example here:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9501954/

).