Physiology Friday #225: Resistance Training at an Old Age Has Lasting Strength Benefits

Long-term muscle memory.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter including Examine.com and my book “VO2 Max Essentials” can be found at the end of the post!

Aging happens to everyone.

But getting old doesn’t have to.

I mean this in the non-literal sense, of course. We all have to age chronologically, but that doesn’t mean we have to sacrifice our health and fitness. Modern science is teaching us more and more about how to run faster, lift heavier, and perform better even as the birthdays add up.

The common thinking is that after about age 30 or 40, we start to get slower and weaker. To add insult to injury — there’s nothing your or I can do about it. Muscle mass, aerobic fitness, and strength all start to undergo a linear decline after about middle age. Eventually, we reach a point where sarcopenia (the age-related decline in muscle size and strength) rears its ugly head and frailty ensues.

But this common thinking is being turned on its head.

What we once thought of as “inevitable” declines in health and fitness are increasingly being recognized as mere side effects of an age-related decline in physical activity. Naturally, most people train less as they get older. When you exercise less, it’s undeniable that you’ll experience some detraining. For some, this detraining is more extreme than it is for others.

If we maintain or even increase our training load with age, it makes sense that we should improve, right? The easy answer is yes, but some would argue that there’s an age at which improvements in muscle strength and size are hard, if not impossible, to obtain. That age is generally recognized to be about 70 or so. Is it a point of no return?

Controlled exercise training studies are attempting to change this outdated thinking, and today’s study is one perfect example.

The LIve active Successful Ageing (LISA) study is a 1-year randomized controlled trial designed to test the effects of resistance training, and subsequent detraining, on strength and body composition in older adults. A recent study published in the British Medical Journal Open presented results of the detraining portion (the follow-up study), which revealed some fascinating insights.1

For the study, a total of 451 older adults (average age of 71 and 61% female) were randomized to a year-long resistance training program that involved heavy loads, a year-long resistance training program that involved moderate loads, or a control group (no exercise).

The participants in the heavy resistance training group performed full-body resistance training thrice weekly, completing 3 sets of 6–12 repetitions of each exercise at an intensity corresponding to 70–80% of their estimated 1-repetition maximum.

The participants in the moderate load group performed circuit training thrice weekly. The program included body weight and resistance band exercises. Each exercise was completed with 3 sets of 10–18 repetitions at an intensity corresponding to 50–60% of the participant’s estimated 1 repetition maximum.

I’ve included details about the two training interventions below, for those interested in the nitty gritty details.

Before the study, after the study, and at the 2-year and 4-year follow up (the results of the 4-year are discussed in the current publication), the participants underwent assessments of muscle strength (power, isometric leg strength, handgrip strength) and body composition (lean body mass, lean leg mass, thigh cross-sectional area, body fat percentage, and visceral fat content).

One important thing to note is that between the end of the study (1 year) and the 4-year follow-up, the participants did not engage in the structured resistance training program, though they likely stayed somewhat active given their baseline physical activity levels.

This study is essentially answering the question of whether gains in resistance training can be maintained over 3 years without structured training.

On that note, let’s look at some results.

Results

Before getting to the 4-year follow-up results, let us take a look at how the outcomes changed from baseline to 1 year (i.e., what were the direct effects of the training program?).

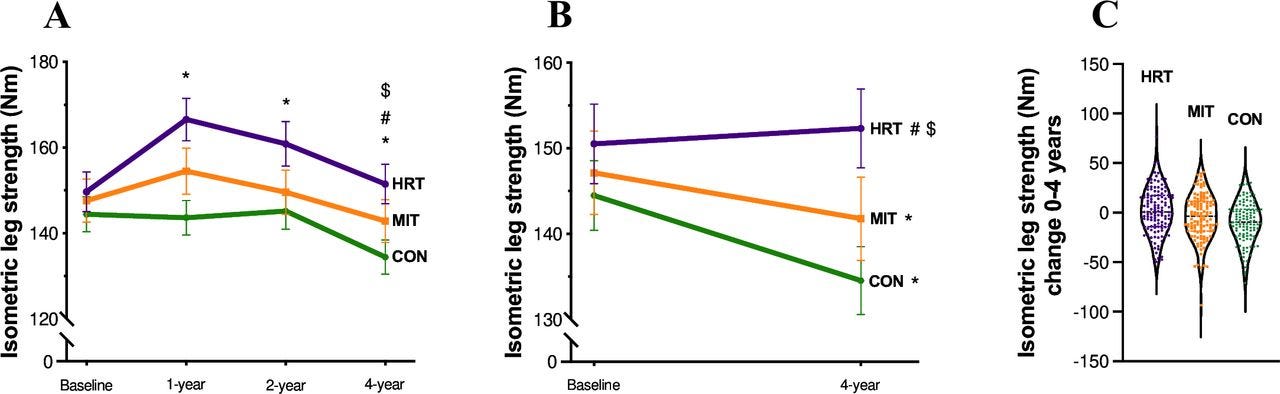

Leg strength increased in the high and moderate load training groups compared to the control group (who experienced a nonsignificant reduction in leg strength).

Handgrip strength and leg power were unchanged between groups, although handgrip strength declined across all groups compared to baseline.

Lean body mass increased in the high load training and moderate load training groups compared to the control group (only the high load training group improved compared to baseline).

Leg lean mass increased in the high load training group (but not the moderate load group) compared to the control group.

Thigh cross-sectional area increased in the high load training group compared to the moderate load group and the control group, who experienced a 3.3% reduction in thigh cross sectional area during the study.

Body fat percentage and visceral fat declined only in the high load training group.

In short: 1 year of heavy or moderate intensity resistance training improves leg strength and lean body mass in older adults, but only heavy load training further improves leg lean mass, thigh cross-sectional area, and body composition. High-intensity resistance training may be necessary to change leg lean mass at an old(er) age.

Now let’s get into the outcomes at the 4-year follow-up time point.

The heavy resistance training group maintained their leg strength compared to baseline over 4 years.

In contrast, the participants in the moderate load training group and the control group experienced declines in leg strength from baseline to year 4 — the reduction in strength was 3% in the moderate load training group and nearly 7% in the control group.

Lower-body power output and handgrip strength declined in all of the group across the 4 year follow-up period. The decline in lower-body power was around 10 kg in the heavy load training group, 14 kg in the moderate load training group, and 16 kg in the control group. While these values were quantitatively different, they weren’t statistically significant between groups.

Handgrip strength declined by about 1 kg, 1.5 kg, and 3 kg in the heavy load, moderate load, and control groups, respectively.

Regarding body composition, lean body mass and visceral fat were the only outcomes that differed between groups. The heavy load training group maintained lean body mass from 47.5 kg at baseline to 47.3 kg at year 4; the moderate load training group experienced a reduction in lean body mass from 46.8 kg at baseline to 46.4 kg at year 4 (a 0.4 kg reduction); and the control group experienced a reduction in lean mass from 46.5 at baseline to 46.0 kg at year 4 (a 0.5 kg reduction).

Visceral fat — the pro-inflammatory fat that wraps around organs and is associated with several diseases — did not change in the heavy load training and moderate load training groups over 4 years. However, in the control group, levels of visceral fat increase by 85 grams (0.085 kg).

Leg lean mass and thigh cross-sectional area declined in all groups from baseline to year 4. Body fat percentage was unchanged in all three groups (it remained around 32–34% on average).

One of the most interesting findings was that leg strength was maintained at 4 years despite a significant reduction in leg lean mass and thigh cross-sectional area.

In other words, strength can be maintained with age in the absence of or even despite adverse changes in muscle size, likely due to the neuromuscular benefits and changes that resistance training induces. It’s also harder to build and maintain muscle with age due to something called “anabolic resistance”, a phenomenon whereby skeletal muscle becomes less responsive to training and/or protein intake. Countering this anabolic resistance takes a lot of stimulus.

But even at age 65–70 (their age at the 1-year study), the participants were able to improve their muscle size (heavy intensity only) and strength with 1 year of training.

This is good news — we can improve muscle strength at any age with at least 1 year of dedicated training and maintain this strength even if we stop training for a few years. I really do think that the idea of “muscle memory” applies here. In fact, it might more accurately be described as “long term” muscle memory. If you get strong at some point, you might be able to stay strong.

Of course, some of the improvements (i.e., lean body mass, leg lean mass, and visceral fat) made after 1 year of training were lost during the 3-year period without training. Thus, the benefit of resistance training in older age was that it prolonged the “inevitable” worsening of these outcomes rather than causing an improvement from baseline. But that’s really the goal of most aerobic and resistance interventions at mid-life and beyond — maintain function for as long as possible. Preventing a decline from occurring is a victory.

The bad news is that at a certain age a decline in functional and structural measures seems somewhat inevitable unless training volume and intensity are maintained: leg strength and visceral fat, for example. Moderate intensity training won’t cut it if you want to preserve these outcomes.

The worse news is that other outcomes decline with age regardless of how much or how hard you train: lower body muscle mass and cross-sectional area, power output, and handgrip strength, for example. At a certain point, these outcomes may lose their plasticity and become unresponsive to training stimuli.

How can you apply these findings?

For one, use this data to encourage everyone you know — no matter how young or old — to keep up or begin a resistance training program. It’s quite literally never too late to start (or start again).

Second, for those of us who haven’t yet reached retirement age, it’s abundantly clear that we should start investing in our “fitness retirement account” right now. As long as we’re able to, we should build muscle size, strength, and functional capacity while we are young. This study makes it clear that even if we were to stop training at some point in life, we’d reap the benefits of our prior good habits for several years or more. And even if we don’t ever plan to stop training, gains made right now will elevate our baseline so that when the “inevitable” declines do start, we’ll be in a much better place.

That’s because some studies suggest we can experience performance reductions even if we train. I like to use the example of VO2 max here, but strength and muscle mass equally apply.

Aerobic capacity declines in everyone with age — in people who are sedentary, recreationally active, and even in masters athletes. But lifelong athletes and physically active people start this downward spiral at a much higher baseline. At age 70, they’re much better off than someone who has been sedentary their entire life.

I see this as optimistic news rather than something to be sad about. We can be proactive about aging.

I think we’re almost out of the era where people claim to be “too old” to do something — especially when it comes to exercise.

Physiology is much more robust than we give it credit for. And as long as we keep giving our bodies the proper stimulus week in and week out, we can stay fit for a long, long time and at some point, maybe take advantage of that “muscle memory.”

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

Great read. Similar to some arguments Peter Attia made in his book. I want to be able to continue to run at 70 and be able to get up off the floor relatively easily. That’d be success!

Very good read. We need to get into the habit of training our bodies, starting small and building it up. Nothing is difficult, we make it complicated but it's not and at any point we can change our mind and start working out!