Physiology Friday #232: Higher Aerobic Fitness Protects Against Declines in Brain Myelination

VO₂ max isn't about performance and longevity anymore.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

A quick plug (and discount code!) for an electrolyte supplement I’ve been loving.

FSTFUEL combines electrolytes with amino acids to help your body maintain hydration and optimal functioning during exercise or intermittent fasting, so you don't have to choose between fasting and fitness. It’s a zero-sugar electrolyte drink that tastes awesome. I use it every single day (no really, I do).

If you want to try some out, the guys at FSTFUEL have agreed to give my audience a 30% discount on their orders. Just use the coupon code BRADY30 at checkout.

Details about the other sponsors of this newsletter including Examine.com and my book “VO2 Max Essentials” can be found at the end of the post!

Do you know your VO₂ max?

You should — it might just be the single best predictor of how well and how long you’ll live.

The idea that cardiorespiratory fitness is important isn’t new — athletes have obsessed over this measure for over a century (VO₂ max just celebrated its 100th birthday) and the link between VO₂ max and mortality was established over 30 years ago.

What is new is the realization by the public and healthcare professionals that VO₂ max isn’t just for athletes — it’s a vital sign that everyone should be concerned with maintaining and improving for the sake of their health.

If you want a comprehensive overview of VO₂ max, its importance for health and longevity, and the science behind improving it, check out my book: VO2 Max Essentials (available as a Kindle eBook or paperback/hardcopy on Amazon).

Based on what I think is strong evidence, people with a higher VO₂ max live longer. It really is “survival of the fittest.”

Some will argue that this correlation doesn’t imply causation. In other words, people who are fitter may live longer not because of their VO₂ max, but because they’ve been genetically gifted with other longevity-enhanced traits. It’s not the fitness per se that’s providing the longevity benefit. While we don’t have long-term randomized controlled studies that show improving aerobic fitness (via exercise) directly translates into increased lifespan, it’s not a difficult leap to make.

Why?

We’ve got plenty of evidence that exercise itself is associated with better healthspan and lifespan, and direct evidence that exercising improves several aspects of cardiometabolic health.

And let’s not forget about the brain — which I think is often neglected in conversations about health and longevity.

Cognitive decline, including Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, is one of the largest causes of death and disability around the world (and all data indicate the rates are rising). When our mind fails, our body follows. And when the body thrives, the mind also seems to reap the benefits.

Indeed, exercise might also be one of the most important things we can do for the brain, but we’re still learning a lot about why.

Perhaps it’s because fitness protects the brain from structural changes that lead to cognitive decline. People who exercise more tend to have better cognitive function, especially late in life. And just a single bout of exercise (especially if it’s high intensity) boosts brain power in the hours after. But we know less about how exercise might impact brain structure. Some evidence suggests that this relationship might involve myelin — the protective casing around our neurons that’s crucial for cognitive health, neuronal signaling, and preventing diseases of brain aging.

The degeneration of myelin in the brain can lead to disruptions in neural communication, which may contribute to the cognitive decline seen in Alzheimer’s disease. Some research suggests that myelin breakdown may even precede the formation of amyloid plaques, one of the hallmark features of Alzheimer’s, indicating that myelin damage could be an early event in the disease's progression. The deterioration of myelin with age is closely associated with cognitive decline. Reduced white matter integrity, which often results from myelin damage, is correlated with declines in memory, executive function, and processing speed in older adults.

As myelin plays a critical role in maintaining efficient neural communication, its degradation can lead to the slowing of cognitive processes and the onset of age-related cognitive impairments — we should do anything and everything we can to increase or maintain levels of brain myelin.

Could being fitter enhance brain myelination? That’s what a new study suggests.1 Let’s dive in.

For the study — which used cohorts drawn from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) and the Genetic and Epigenetic Signatures of Translational Aging Laboratory Testing (GESTALT) — a total of 125 adults without cognitive impairment (average age of 56 and 54% men) underwent brain imaging to quantify the level of myelin content throughout several brain regions. This was done using a direct and specific proxy of myelin content known as whole-brain and local myelin water fraction. Unless you’re a neuroscientist (I’m not), the specifics here aren’t as important. Just know that less myelination is a bad thing and more myelination is a good thing.

All of the participants underwent a treadmill test to measure their maximal oxygen consumption or VO₂ max (a major strength of the study because rather than an estimation of their aerobic fitness, we get a direct measure).

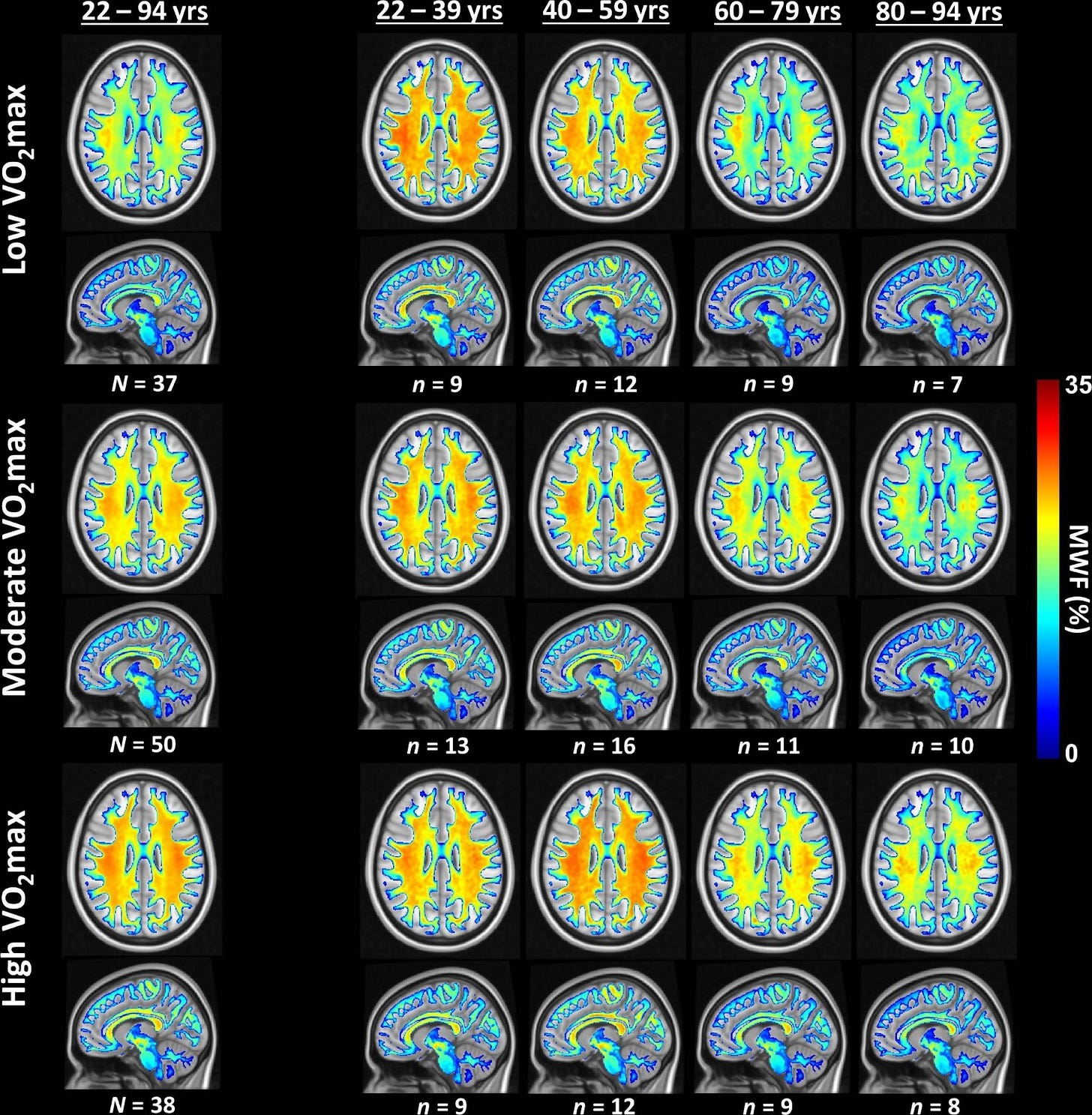

The researchers divided the participants into three groups based on their level of aerobic fitness: low (below the 30th percentile), moderate (between the 30th and 70th percentile), and high (above the 70th percentile). They also examined the effect of age by dividing the participants into age categories: 22–29, 40–59, 60–79, and 80–94.

Results

As is clear in the image below, the participants with a lower VO₂ max had less myelination (more green and blue on the brain scan) while those with a higher VO₂ max had higher myelination (more red and orange on the brain scan). This was most apparent among the participants in the middle-aged and older age groups, suggesting that fitness provides even more protection against brain demyelination with age.

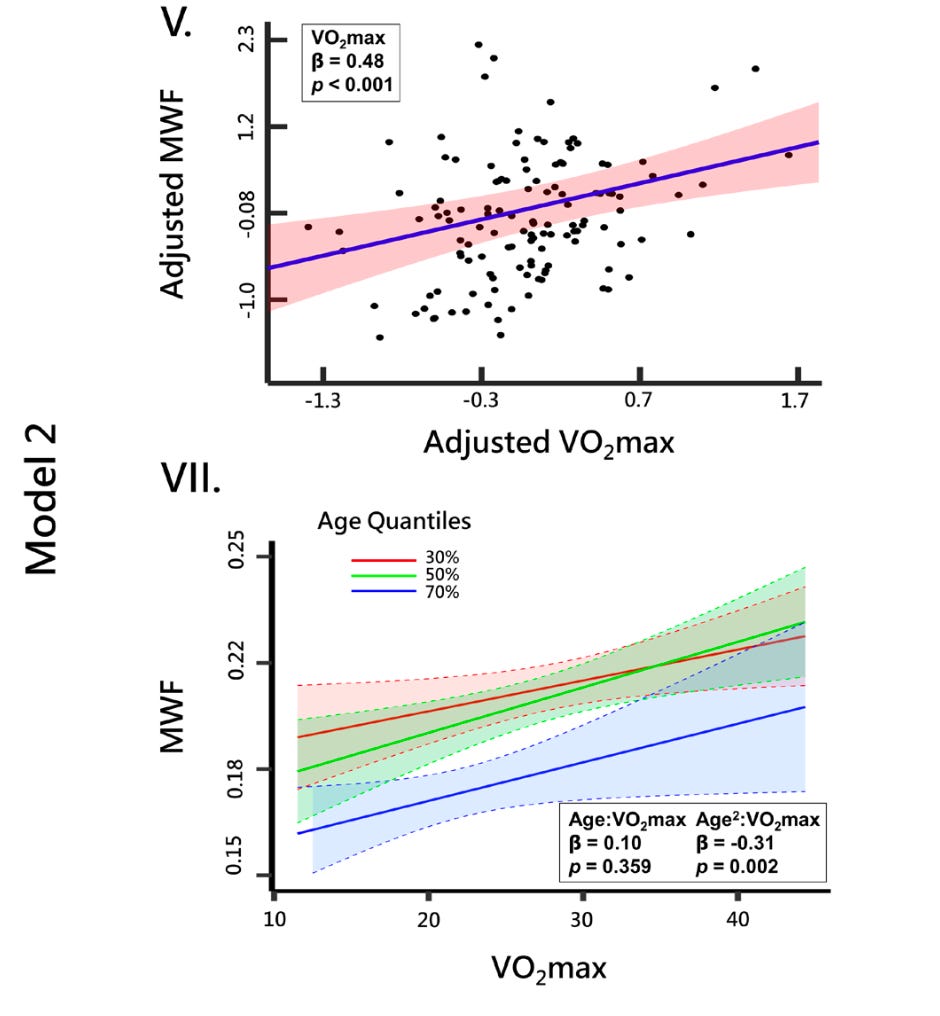

Aerobic fitness was positively correlated with brain myelination — as VO₂ max increased, myelination increased, and vice-versa. This finding was observed across nearly all of the brain regions that were imaged.

Again, fitness also proved to be more important for brain health at an older age. The oldest participants experienced the greatest increase in myelination as fitness improved (they’re the blue line in the plot labeled VII below), followed by participants in middle age (they’re the green line in the plot labeled VII below). Notice the steep slope of the blue line compared to the other lines (the younger age groups).

Having better fitness was also associated with a slower decline in brain myelination and a later peak in brain myelin levels.

For the entire group of participants, peak myelination occurred around age 31, after which myelin levels began to decline. However, in the participants with the lowest VO₂ max, myelin levels peaked before age 22 and had a more rapid decline. For participants in the middle VO₂ max group, peak myelination occurred at age 28, and for the participants in the highest VO₂ max group, peak myelination didn’t occur until age 41.

In short, having poor fitness hinders the process of myelination in the brain and causes an earlier and more rapid onset of myelin deterioration. Not good.

This is, in my opinion, some strong mechanistic support for the idea that aerobic fitness directly leads to changes in the brain that promote better cognitive resilience with aging. Not only can we say that physical activity and fitness are associated with better brain function, but we can also speculate (with evidence) why this might occur.

With better fitness, you get a later peak in brain myelin, a higher level of peak myelin, and a slower decline in myelin. If you analogize this to muscle mass (which follows a similar trajectory), it becomes clear how important these implications are for brain health.

How might fitness protect myelin in the brain?

For one, exercise stimulates the production and activity of oligodendrocytes, the cells responsible for producing and maintaining myelin. Physical activity can enhance the proliferation of these cells and their ability to form new myelin sheaths around neurons, aiding in the repair of damaged myelin.

Exercise also enhances levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports the survival and growth of neurons and promotes myelination. Exercise decreases myelin degradation by reducing inflammation, and it also enhances brain metabolic function, which is known to play a role in several neurodegenerative diseases (some people are beginning to call Alzheimer’s disease “type 3 diabetes”, although this isn’t a universally accepted term).

The usual questions and caveats apply here. Is there a limit to the protective effects of fitness on the brain? The participants in this study weren’t that fit — their VO₂ max ranged from 10 on the low end to ~50 on the high end. Are the brains of superior endurance athletes even more heavily myelinated than those of mere mortals? We don’t know.

And we still can’t imply causation from this association (even though it’s always tempting). We don’t know if getting fitter increases brain myelin levels. Does the decline in myelin mirror the age-related decline in aerobic fitness?

Nevertheless, we can now add “brain health” to the ever-growing list of things that cardiorespiratory fitness appears to benefit.

So, even if you aren’t concerned about improving your VO₂ max to live longer or run faster, you can at least be prudent about improving it for the sake of your brain. That seems to be a smart decision.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.