Physiology Friday #277: Exercising Earlier in the Day (and Being Consistent About It) May Lead to Better Fitness

Adults who maintain regular, robust rhythms in their physical activity have a higher aerobic capacity and physical performance than their "less rhythmic" peers.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

If you’ve jumped on the creatine bandwagon (who hasn’t) but aren’t sure where to start, I suggest you try out Create—the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of gummies (including a new sour cherry flavor), flavored creatine monohydrate single-serve packets, and even a daily performance mushroom & greens gummy (my personal favorite).

They’re giving my audience 20% off of their entire order. So stock up!

Details about the other sponsors of this newsletter, including Ketone-IQ, Examine.com, and my book “VO2 Max Essentials,” can be found at the end of the post. You can find more products I’m affiliated with on my website.

Our bodies crave consistency.

And in biology, circadian rhythms are the definition of consistency. At least they should be.

When circadian rhythms are aligned, robust health ensues. Environment matches behavior matches physiology. Waking up at a similar time each day, eating three square meals, and being active throughout the day (and not at night) help our body know when it should be performing various functions like digesting food or releasing cortisol and melatonin (and similarly, when it shouldn’t).

When things are out of sync, bad things happen. This is referred to as the ‘circadian disruption hypothesis.

When we engage in activities like eating, sleeping, and even exercising at odd times of the day (for us), we can throw the body’s clocks out of their normal rhythm. Night shift workers are the epitome of circadian disruption—they’re forcing their body clocks to perform essentially the reverse of what’s considered “normal” by human biology standards.

Everyone recognizes that performing physical activity (or exercise) at any time of the day is beneficial. But given what we know about circadian biology, it’s worth contemplating whether being more regular about one’s activity by engaging in exercise at a similar time of day every day may offer unique health benefits. Could we optimize exercise by being more consistent about it?

Researchers from several Universities (led by Dr. Karyn Esser from the University of Florida, my alma mater) leveraged wearable data to investigate this hypothesis by observing whether daily physical activity rhythms were related to cardiorespiratory fitness (i.e., VO2 max) and walking performance among adults 70 years and older.1

(If you’re into the metrics used in this study and how they’re defined, make sure to read the next two sections. If you’re not interested in the nitty-gritty details, you can skip to the results…though I discourage it. Context is key!)

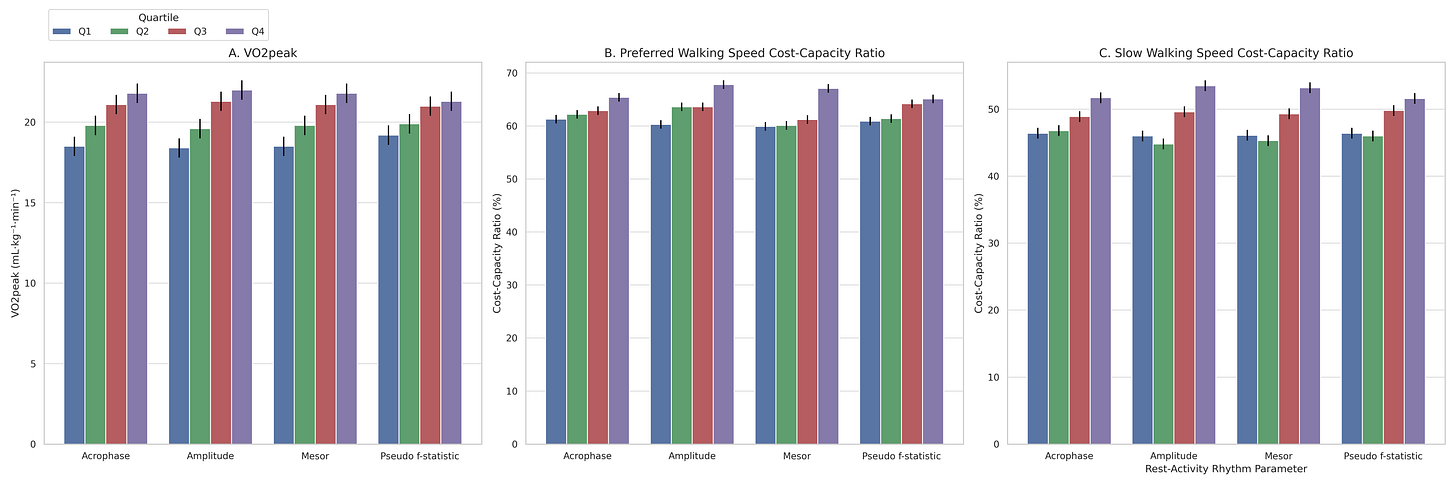

Cardiorespiratory fitness was measured using a standard but modified maximal treadmill walking test (these were older adults after all). Walking performance was defined using several different measures of walking efficiency: the cost-capacity ratio (the percentage of one’s maximum aerobic capacity that it takes to sustain a preferred or slow walking speed), the energy cost of walking at various speeds (basically, walking economy), and energy reserve—the difference in oxygen consumption between someone’s maximum oxygen consumption and oxygen consumption at a slow walking speed.

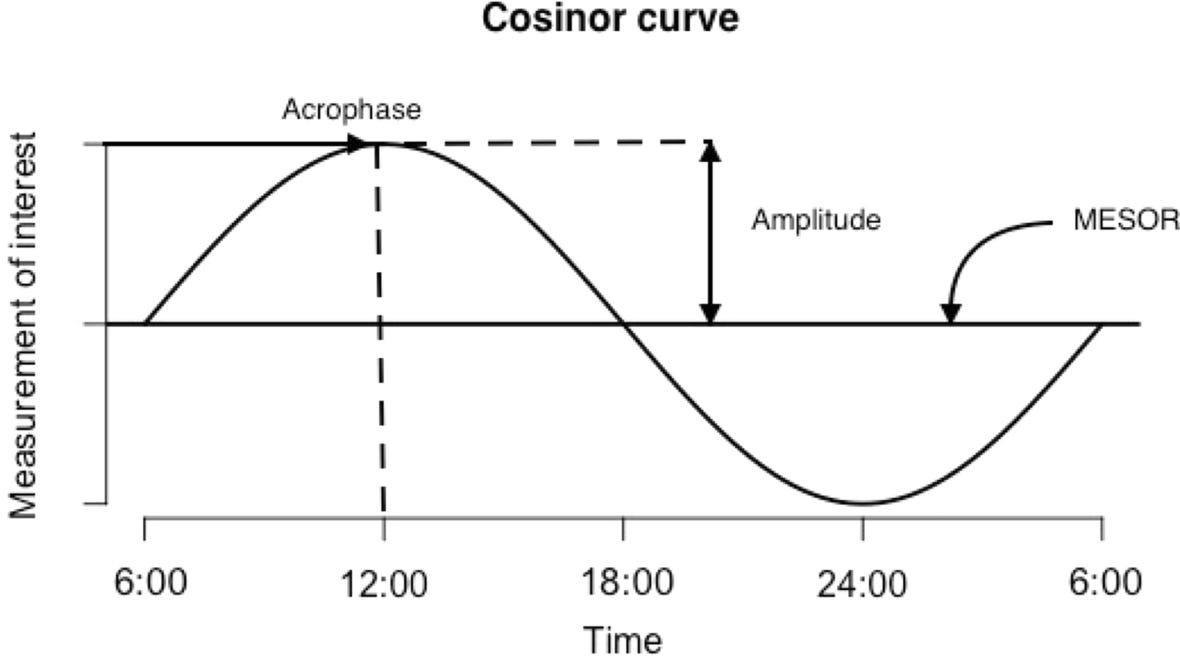

Each participant’s physical activity data were gathered with an activity tracker. The researchers were interested in a few key variables. The primary one was the amplitude of activity—the difference between the highest and lowest activity levels during the day. If we think of activity levels as a series of undulations (resembling a cosine wave form), then a greater amplitude is represented by large peaks and troughs (see an example below, along with other definitions of interest).

Other variables included the average level of daily activity (mesor), the consistency of activity amplitude over multiple days (the pseudo f-statistic), the time of day when peak physical activity levels occurred (acrophase), the stability and durability of activity from day to day, the average activity level of each participants’ most active 10-hour and least active 5-hour period, and the difference in the activity level between the participants most-active 10-hour and least-active 5-hour period (defined as the relative amplitude).

Results

A higher amplitude of activity, a higher daily average of physical activity (mesor), and a higher consistency of peak and trough physical activity rhythms (pseudo f-statistic) were associated with better aerobic fitness, with a graded increase from small amplitude & less robust rhythms to higher amplitude & more robust rhythms.

When participants engaged in their highest levels of activity (the acrophase) also emerged as an important factor. An earlier acrophase—performing one’s highest levels of activity earlier in the day—was associated with better cardiorespiratory fitness.

Cardiorespiratory fitness was also positively associated with other variables of physical activity consistency—better stability from day to day, less day-to-day variability, a lower least active 5-hour period, a higher most active 10-hour period, and a greater difference between the two.

Tl;dr version: The higher the consistency and stability of one’s daily physical activity patterns, the better their cardiorespiratory fitness.

The story was largely similar for walking energetics—most measures of physical activity amplitude, an earlier peak in activity, more day-to-day consistency, and less day-to-day variability were associated with more favorable walking economy, a better cost-capacity ratio, and better energy reserve.

The researchers also conducted an additional analysis to look at the role of aging in activity rhythms and their association with fitness.

They found that VO2 max declined by ~1.4 ml/kg/min per 5 years of aging; however, maintaining a high physical activity amplitude attenuated this relationship by 21%. Participants who maintained a high amplitude in their rest-activity rhythms experienced less of a decline in VO2 max with age (a ~1 ml/kg/min decrease per 5 years).

Importantly, all of these associations were found to be independent of physical activity levels. Participants with better fitness and superior walking energetics weren’t just more physically active overall—the timing and consistency of their physical activity appeared to contribute to their better physiological robustness compared to their “less rhythmic” peers.

Here are the two most important findings from this study, in my opinion:

An “early active” behavior phenotype—characterized by peak activity levels happening earlier in the day versus later on—is associated with higher levels of cardiorespiratory fitness.

Morning people, rejoice.

Early activity might just reflect a behavioral preference, and this doesn’t necessarily mean that working out early in the day causes someone to be fitter than someone who works out later in the day. However, there is some (emphasis on some) evidence that working out in the morning may have more favorable benefits on cardiorespiratory fitness, metabolic health, and blood pressure compared to the same workout later on in the day. Why that’s the case, I’m not quite sure, but there seems to be something unique to early- or late-morning workouts that align with human biology and physiology.

When you perform your exercise during the day isn’t the most important variable (other factors like duration and intensity matter far more), but it’s not unimportant.

Maintaining a robust rest-activity amplitude throughout life probably negates the decline in several fitness-related variables, as shown by an attenuation in the age-related decline in aerobic fitness for the participants with higher circadian amplitudes in activity.

Unrelated to when one performs an activity, it also seems important to be very active when you’re active and very inactive when you’re not (e.g., when you’re asleep). A high amplitude in physical activity means higher highs and lower lows, as opposed to a low-amplitude profile with smaller peaks and troughs.

Could all of this be reverse causation? The authors of the study readily admit that “it is not possible to determine if dampened rest-activity rhythms contribute to aging, or rather if other intrinsic aging processes contribute to dampened and disordered rest activity rhythms and other health effects.”

That’s fair—someone who’s sick and disabled will naturally have dampened activity rhythms and less consistency than someone who’s physically able and vibrant. And there is a well-known change in circadian rhythms of sleep and activity with age…but this study suggests that might be more a consequence of behavior than some intrinsic aging biology. Fascinating stuff.

However, biology supports the idea that curating a more favorable (i.e., consistent) activity profile leads to improvements in health. I’ll quote the study again because it phrases this idea in a way that I couldn’t: “We posit that this occurs because the consolidation of known circadian clock timing cues, including light, time of feeding, and activity serve to support alignment of the cell and tissue endogenous molecular clocks across all central and peripheral tissues for metabolic and physiological health.”

In plain English: If you’re consistent with when you exercise and eat, the body benefits immensely.

The takeaway here isn’t that you need to change when you exercise—that’s largely going to be determined by your work schedule, social life, and family obligations.

Rather, it suggests that you find a time that works best for you to exercise and keep it the same from day to day—whether it’s before sunrise, on your lunch break, or after the kids go to bed. Just be consistent.

Or should I say rhythmic?

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off of your order.

This is a great read!! I was a "Whenever I can get a workout" person until about 10 years ago as I'm more of a night owl and just naturally stay up late. Due to a lifestyle shift (did triathlon where cycling at 5am was the normal, a partner who wakes up early and having a kid).

I'm now def a morning workout person. I was able to train (no pun intended) my body to like the mornings. Now if I go any later than 8 or 9am I feel weird and everything is "off". The body really does crave rhythm and its' great to know that fitness gains come with that consistency... which is one of the sections of my upcoming book "The 1% Better Runner"

To quote the legendary Villanova track coach Jumbo Elliott: “Live like a clock.”