Physiology Friday #281: Is Being Fit and Overweight Healthier Than Being Unfit?

Maybe you can outrun a bad diet after all…

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

If you’ve jumped on the creatine bandwagon (who hasn’t) but aren’t sure where to start, I suggest you try out Create—the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of gummies (and yeah…their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands), flavored creatine monohydrate single-serve packets, and a daily performance greens gummy (my personal favorite).

They’re giving my audience 20% off of their order. So stock up!

Details about the other sponsors of this newsletter, including Ketone-IQ, Examine.com, and my book “VO2 Max Essentials,” can be found at the end of the post. You can find more products I’m affiliated with on my website.

I’m a fitness fanatic (some would call me an ‘exercist’).

If you’ve followed my work for any length of time, you know I’m also a huge advocate for VO₂max. It’s one of the strongest predictors we have for mortality risk, and higher numbers consistently mean longer, healthier lives. But even I’ll admit it: VO₂max doesn’t tell the whole story.

A recent perspective article makes the case that while VO₂max is excellent for predicting overall survival, it may be less precise for gauging metabolic health.1 Two people with the same VO₂max can have very different mitochondrial function and metabolic flexibility (ability to switch seamlessly between burning fat and carbs during exercise). Those differences matter, especially when it comes to insulin sensitivity, fat oxidation, and overall metabolic health, which are also important for longevity.

The authors argue for pairing VO₂max with other measures, such as submaximal exercise testing to assess fat oxidation (including fatmax, the point at which fat burning peaks) and exercise efficiency. These markers can reveal metabolic strengths or weaknesses that VO₂max alone might miss.

It’s a compelling case backed by data, and suggests that someone can be “fit” by cardiorespiratory fitness standards while still perhaps not exhibiting characteristics that are consistent with someone “metabolically healthy,” which they define as having optimal insulin sensitivity, blood glucose levels, blood lipids, blood pressure, and a body mass index (BMI) in the normal (i.e., non-overweight or obese) range.

Well, the idea that “fitness” can be defined in more than one way is the perfect setup for a new meta-analysis exploring the relationship between fitness, body weight, and mortality risk.2 It forces us to rethink some of our assumptions of what healthy might look like and the relative importance of weight versus physiological function in long-term disease reduction.

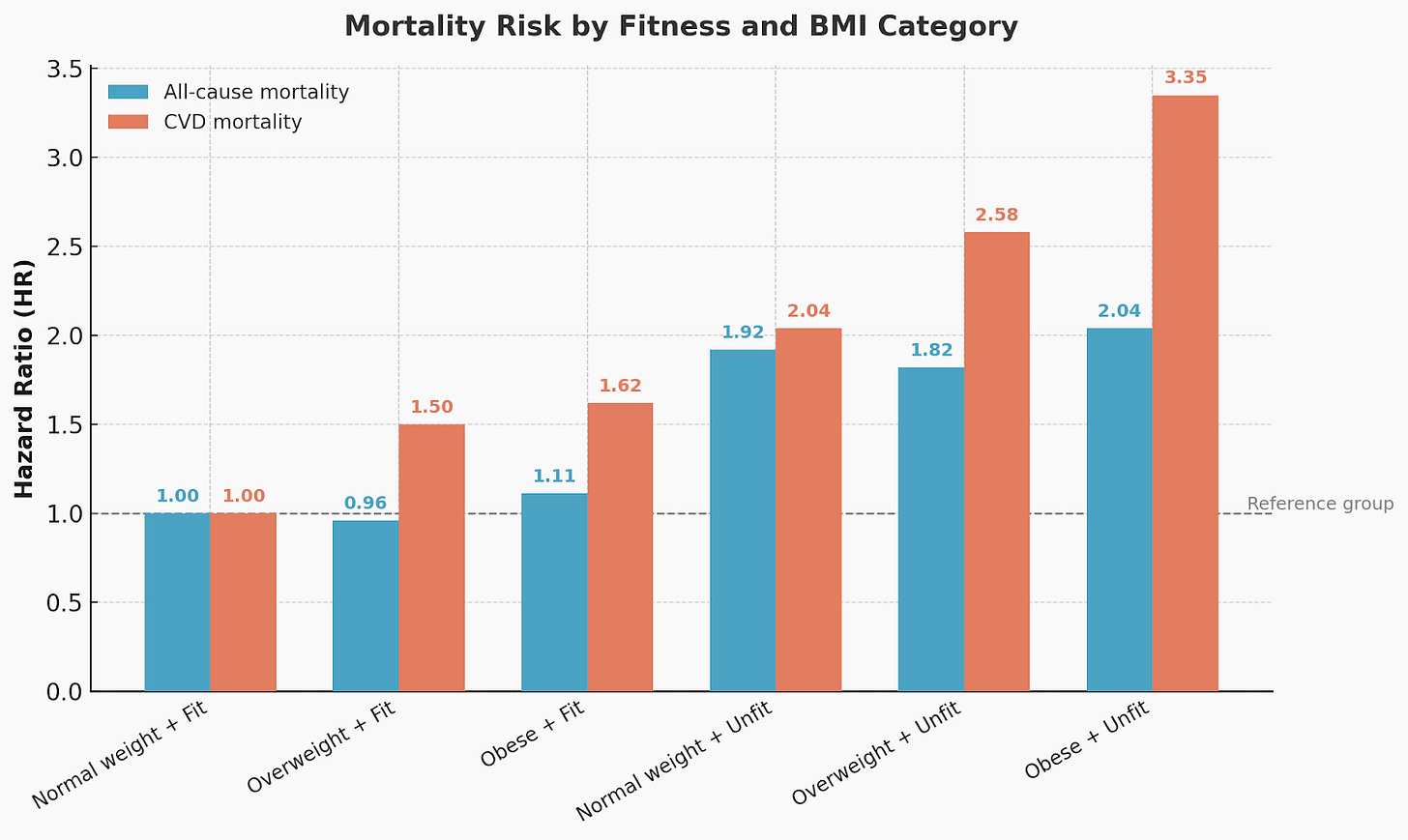

The study pooled results from 20 prospective cohorts, totaling nearly 400,000 participants, all of whom completed maximal exercise testing to measure cardiorespiratory fitness. Participants were categorized by BMI as normal weight, overweight, or obese, and fitness level (“fit” or “unfit” based on age-adjusted VO₂max). The reference group—normal-weight and fit—was compared with all other combinations.

This meta-analysis stands out from earlier work because it includes more women; participants from a broader range of ages, health statuses, and geographic backgrounds; and better statistics. That means the findings are more generalizable and the results more precise.

Compared to the reference group of normal-weight individuals with high fitness, those who were both overweight and fit and obese and fit had virtually the same risk of dying from any cause (about 4% lower and 11% higher, respectively, which was not statistically significant). Fitness protected against overweightness for all-cause mortality.

Low fitness painted a much different picture. Normal-weight but unfit individuals had a 92% higher all-cause mortality risk, and the risk was similarly high for overweight (82% higher) and obese (104% higher) unfit individuals.

The pattern was similar for cardiovascular disease mortality, though the differences between weight categories were more pronounced. Fit individuals with overweight had a 50% higher risk, and those with obesity had a 62% higher risk than normal-weight fit people, though neither was statistically significant, again meaning that being fit protected against the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease.

But for unfit individuals, the numbers skyrocketed: 104% higher risk for normal weight, 158% for overweight, and a 235% higher risk for those with obesity.

In other words, being unfit more than doubled mortality risk in many cases, regardless of BMI, while being fit often neutralized the impact of carrying extra weight.

These findings challenge weight-centered thinking. BMI alone is a weak predictor of health (at least in this analysis), and improving cardiorespiratory fitness can neutralize (or at least blunt) much of the risk associated with a higher BMI.

Interestingly, for cardiovascular mortality, fit individuals with overweight or obesity still had risk estimates above 1.0 (a hazard ratio of 1.0 means that the risk isn’t different from the control group, and values above and below 1.0 indicate higher and lower risks, respectively), hinting that a higher level of fitness may be needed to fully erase CVD risk in these groups.

One important note: in many included studies, “fit” meant being above about the 20th percentile of age-adjusted cardiorespiratory fitness, which suggests that you don’t have to be elite. Just moving from “low fit” to “moderately fit” can be life-changing and attenuate risks associated with being overweight or obese.

The “Bigger Engine” Effect

One intriguing question is why didn’t fit individuals with overweight or obesity have a higher mortality risk? One hypothesis is that to match the relative aerobic fitness of a lighter person (relative fitness is scaled to body weight), a heavier individual must have a higher absolute VO₂max because of the larger body mass (and possibly more muscle mass). This “larger engine” may stimulate muscle signaling pathways that offset some of the health risks of carrying extra weight. That does align with some studies that show absolute VO₂max may be more strongly related to lower disease risks than relative VO₂max.

Someone who is overweight might have to train harder and get technically “fitter” to achieve the same VO₂max as a lighter person. This is all a bit speculative, of course.

Does this mean we should prioritize fitness promotion over weight loss in public health messaging? Possibly. Right now, policy often focuses on dietary reform (like reducing processed foods) while physical activity gets less emphasis. This study suggests that boosting fitness should be at the top of the to-do list, not as a replacement for tackling obesity, but as a parallel priority with immediate and measurable benefits. Given the failure of most weight-loss programs, exercise promotion also seems potentially more efficacious and implementable.

This is where the perspective article on VO₂max may undervalue the ability of cardiorespiratory fitness to predict general physiological ‘robustness.’ The meta-analysis shows that being “fit” by VO₂max standards can dramatically reduce mortality risk across weight categories. So maybe traditionally measured cardiorespiratory fitness is a pretty darn good measure of whole-body metabolic health after all. It must be, to have such a strong effect on mortality risk—strong enough to nullify the effects of overweight and obesity, which are pretty well known to be associated with poorer long-term health outcomes.

Data like this is one of the main reasons I often say (somewhat tongue-in-cheek) that physical activity is way more important than diet for those looking to live a long, healthy life. It’s simply indispensable. Which isn’t to say “diet doesn’t matter.” However, fitness is king.

But the perspective reminds us that how you build that fitness—and whether you also improve mitochondrial health and metabolic flexibility—still matters for long-term vitality.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Interesting read, thanks Brady. I agree, "boosting fitness should be at the top of the to-do list...as a parallel priority with immediate" but suggest the "failure of most weight-loss" programs is in no small part because we continue to use the term "weight loss". https://leftfieldtraining.substack.com/p/weight-lost-in-translation

The way you show fit ≠ healthy (and how VO₂max misses fat oxidation/insulin nuances) hit home. Especially the insight that moving from “unfit” to “moderately fit” can dramatically lower mortality risk. Wow