Physiology Friday #301: Does Creatine Change How Much Sleep You Need?

An unintended "benefit" of the popular supplement.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter and deals on products, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, Equip Foods, and ProBio Nutrition can be found at the end of the post.

Creatine is still having a moment, but lately the buzz is increasingly about the brain. People are interested in whether creatine can meaningfully support neural energy metabolism, cognition under stress, or even resilience to sleep loss.

The framing makes sense. The brain is an energy-hungry organ, and a lot of what we experience as “mental fatigue” is an energy problem—slower thinking, fuzzier attention, more emotional volatility, worse impulse control, etc…

The study I’m covering today is actually one I wrote about years ago, but it was a line of research that changed my behavior immediately.

At the time, my wife was pregnant, and I was staring down the very real prospect of functioning on less sleep for an extended stretch. I came across a rat study suggesting that creatine supplementation might reduce homeostatic sleep pressure (in simple terms: less need for sleep). If sleep loss is partly a brain-energy problem, and creatine can buffer energy availability, maybe it could make the inevitable sleep restriction less cognitively expensive.

That personal context is also why I think this paper is worth revisiting. The study itself is nearly a decade old, but the applications feel evergreen and arguably more relevant now than when it was published. Since then, newer data have continued to build interest in creatine’s effects on cognitive performance after sleep deprivation, and there’s been growing attention on the idea that creatine doesn’t necessarily accumulate meaningfully in the brain overnight. In many cases, it likely requires prolonged supplementation—and possibly higher-dose strategies in certain contexts—to measurably shift brain creatine/PCr availability.

I’ve always found the “brain energy” hypothesis of sleep so compelling. One long-standing idea is that sleep (especially non-rem or NREM sleep) functions as a low-energy state that helps restore or rebalance energetic demands built up during wakefulness. The authors of the study I’m rewriting here point to evidence that NREM sleep is associated with large reductions in metabolism compared with wakefulness and REM sleep, including reductions in glucose and oxygen utilization. If sleep pressure is, at least partly, an energy story, then you can ask a compelling question: if you increase energy availability (or energy buffering) in the brain, do you need less sleep?

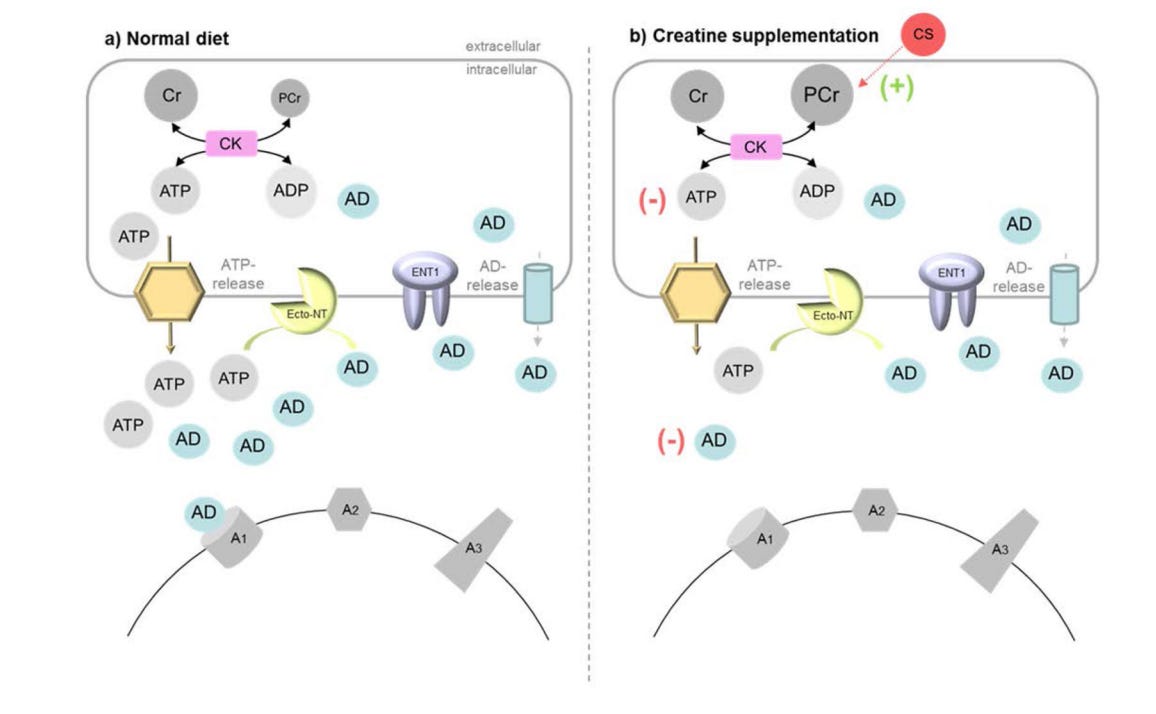

Creatine is a reasonable tool to test that idea because it sits at the center of a rapid energy-buffering system. Creatine and phosphocreatine (PCr) help stabilize ATP availability when energy demand changes quickly—something that matters in tissues like skeletal muscle and the brain. The researchers behind this paper asked whether chronic creatine supplementation could reduce homeostatic sleep pressure—particularly after sleep deprivation—by altering brain energetics and the accumulation of adenosine, one of the key molecular signals tied to sleepiness (adenosine is what caffeine blocks and hence, why it makes us feel less tired).

What they found is genuinely interesting: rats supplemented with creatine spent more time awake, less time in NREM sleep during their normal rest phase, and, most strikingly, showed a blunted “sleep rebound” after being kept awake. Alongside this, creatine attenuated the sleep-deprivation–induced rise in adenosine in a brain region heavily implicated in sleep–wake regulation.1

If you needed yet another reason to start supplementing with creatine (or to up your dose), this study might be it.

The researchers studied male rats housed on a standard 12-hour light/dark cycle. Rats were fed chow containing 2% creatine monohydrate for four weeks. Before and after the 4-week supplementation, the rats’ sleep-wake behavior and brain bioenergetics were assessed after a baseline night, after 6 hours of sleep deprivation (enforced wakefulness), and after a night of recovery sleep.

Sleep was categorized as wake, NREM sleep (slow-wave sleep or SWS), and REM sleep. They also quantified NREM delta activity, which is one of the most widely used physiological readouts of homeostatic sleep pressure—when you deprive an animal of sleep, delta power rebounds upward during recovery sleep.

Sleep deprivation was straightforward: six hours of enforced wakefulness from 7 am to 1 pm (the light period, when rats normally sleep). Researchers also analyzed adenosine levels in specific brain regions in a subset of rats. To examine brain energetics more directly, they measured creatine, phosphocreatine, and ATP levels in multiple brain regions (i.e., frontal cortex, basal forebrain, cingulate cortex, hippocampus).

Creatine alters sleep-wake behavior and brain energy metabolism

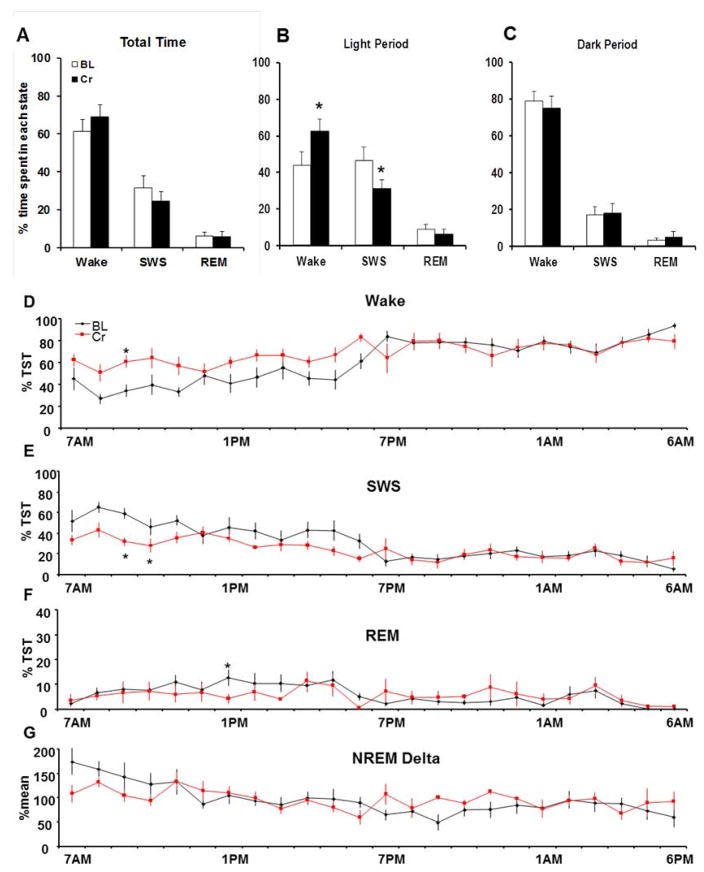

Under normal (undisturbed) 24-hour conditions, creatine shifted sleep-wake balance in a time-specific way. After four weeks of supplementation, rats spent substantially more time awake during the light period (their normal rest phase), with wake time rising from 43.7% at baseline to 61.4% after creatine. Total sleep time during the light period fell in parallel, dropping from 54.9% at baseline to 37.2% after creatine.

When the researchers broke down sleep stages, the reduction in sleep was driven primarily by less NREM slow-wave sleep (SWS). During the light period, SWS decreased from 46.3% at baseline to 31.1% after creatine. REM sleep, meanwhile, was largely unchanged in total amount. Despite the animals spending more time awake and less time in SWS, average NREM delta activity across the undisturbed (non-sleep-deprived) condition did not show an overall change. That detail matters because it suggests creatine altered sleep duration more than it altered baseline “sleep intensity” signals.

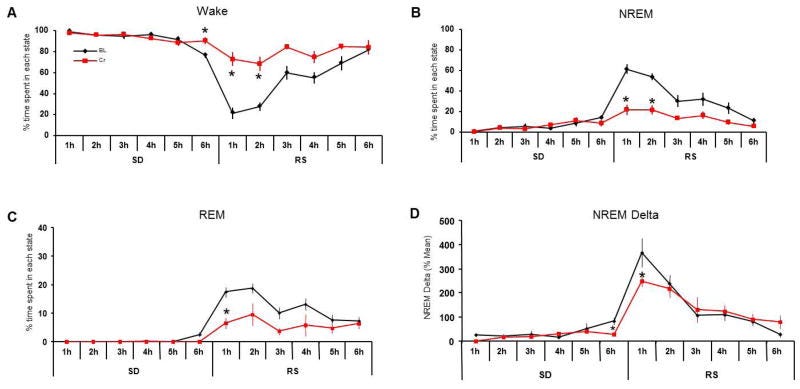

The more dramatic effects emerged after sleep deprivation. As expected, six hours of enforced wakefulness produced classic recovery behavior at baseline: an early rebound characterized by increased sleep and elevated NREM delta activity, reflecting heightened homeostatic pressure. But after creatine supplementation, that rebound was noticeably muted. In the first two hours of recovery sleep, the creatine condition showed significantly less NREM and REM sleep compared with baseline, with wakefulness remaining elevated. Even more telling, the hallmark signal of sleep pressure (NREM delta activity) was sharply reduced during early recovery: delta power in the first hour of recovery sleep was 66.3% lower than baseline and 32.7% lower in the second hour.

In plain terms, creatine-supplemented animals behaved as though they were less “in debt” after being kept awake.

That pattern—less rebound sleep and lower delta activity—is the core physiological case for the paper’s claim that creatine reduced homeostatic sleep pressure.

Adenosine rises less during sleep deprivation

During sleep deprivation under baseline conditions (without creatine), adenosine levels in the basal forebrain rose robustly and peaked after six hours. After creatine supplementation, the rise in adenosine during sleep deprivation was significantly attenuated: baseline levels increased by 239.4%, whereas after creatine, they increased by 151.7%. During recovery sleep, adenosine did not show significant differences.

This result is where the “brain energy” framing starts to feel like a very plausible mechanistic pathway: if creatine changes energy buffering in a way that reduces the buildup of adenosine during extended wakefulness, then the brain may signal less urgency to recover sleep!

But here’s where it gets interesting… the paper challenges the intuition that creatine should increase ATP levels.

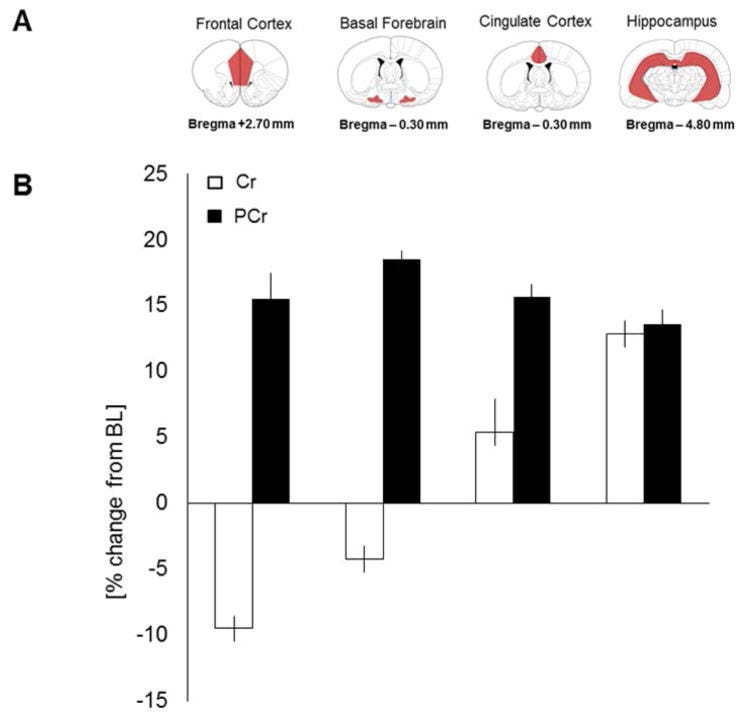

When they measured creatine and phosphocreatine in multiple brain regions, they did not find statistically significant increases in tissue creatine or PCr. But they repeatedly note a trend toward increased creatine and PCr in multiple regions (as you can see in the graph below).

ATP, on the other hand, clearly moved—and in the opposite direction many people would expect. After two weeks of creatine supplementation, ATP was significantly lower in the frontal cortex (~52% decrease), the basal forebrain (~46% decrease), and the hippocampus (~37% decrease). In the frontal cortex and hippocampus, ATP declined further by week four, while the cingulate cortex did not show a significant overall change.

The authors’ interpretation is not that creatine “depletes energy,” but that supplementation may alter the balance between ATP, PCr, and creatine.

And that leads to their central mechanistic proposal: adenosine is one of the brain’s main “you need sleep” signals, and it tends to build the longer you stay awake. One reason it builds is that brain cells release ATP (the cell’s energy currency) into the space outside the cell, where enzymes break it down into adenosine.

The authors argue that creatine changes the brain’s energy balance, so during prolonged wakefulness, less ATP gets released and broken down into adenosine. If adenosine rises less, the brain experiences less sleep pressure, and you see a smaller rebound in deep sleep after sleep deprivation.

The most intriguing aspect of this paper (to me) is not that creatine lets you sleep less. It’s that a nutritional intervention appears to modify a core homeostatic sleep signal (adenosine).

If you care about cognition under sleep restriction, shift work, new parenthood, travel, or any situation where you can’t reliably get enough sleep, this is exactly the kind of mechanistic lens we should care about (ok… the potential application might be nice too).

But there are real cautions. The sleep architecture change here is heavily driven by reductions in NREM slow-wave sleep, and whether that is benign, beneficial, or harmful (especially to humans) depends on outcomes that this study did not test, like learning, memory, synaptic plasticity, immune function, metabolic regulation, and so on. Needing less sleep is one thing… but performing well with less sleep and not experiencing adverse consequences is another.

In other words, this study is best read as a mechanistic experiment about sleep pressure and energy signaling and not an excuse to sleep less because you’re taking creatine.

That being said, this experiment is something I “restarted” in the last few weeks as I’ve shifted my wake-up time a bit earlier (and lost about 30—45 minutes of extra sleep as a consequence). I’ve upped my creatine dose to 10 grams per day, and I feel like it’s allowing me a little extra cognitive energy and “wiggle room” when I need it most.

Your mileage may vary.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 20% off their order.

ProBio Nutrition—the all-in-one supplement that I use every single day—is offering 20% off. My preference is the tangy orange flavor, but they also sell an unflavored “smoothie booster” that’s great in a shake, smoothie, or juice.

Equip Foods makes some of the cleanest, best-tasting protein products around. I am absolutely obsessed with their Prime grass-fed protein bars (the peanut butter ones are to die for). Take up to 10% off site-wide!

Thanks for the read! Another benefit of Creatine I was not aware of.

What do you have against figure captions?