The Ultimate Guide to Sleep and Cardiovascular Health

All you need to know about the importance of sleep for your heart.

“Innocent sleep. Sleep that soothes away all our worries. Sleep that puts each day to rest. Sleep that relieves the weary laborer and heals hurt minds. Sleep, the main course in life's feast, and the most nourishing.”

―William Shakespeare, Macbeth

If you’re a paid subscriber, scroll down to the end of this post for a link to download a PDF version of The Ultimate Guide to Sleep and Cardiovascular Health.

Sleep and cardiovascular disease: the epidemiological evidence

Despite our knowledge that sleep is vital for human health and well being, we often neglect it.

More than one-third of U.S. adults report sleeping less than 7 hours each night and another 30% sleep fewer than 6 hours.23

As many as 48% of adults fail to get the proper amount of sleep each night,4 which is 7-9 hours according to the latest recommendations from the National Sleep foundation.5

Around 20% of college students report staying up all night at least once per month.6

Insufficient sleep has been linked to a greater risk for several health conditions including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cognitive decline.78

Sleep may have also played an underemphasized role in the COVID-19 pandemic.

In a commentary published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, sleep experts Christian Benedict and Jonathan Cedernaes argue (with data) that a poor night of sleep before or after a vaccination could possibly reduce its efficacy.

Sleep also has a crucial role in regulating our cardiovascular and autonomic nervous system. A lack of sleep causes the dysregulation of several cardiovascular functions which, over time increase CVD risk.

Habitually short sleep duration is consistently linked to greater CVD risk.

In a cohort of >3,000 people from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), sleeping <6 hours each night predicted a higher prevalence of stroke, heart attack, and chronic heart failure.9

Adults who sleep <6 hours each night have a 15% greater risk for CVD and 23% increased risk for coronary heart disease compared to those sleeping 7 hours or more.10

In a group of 30,397 adults (57% women), self-reported short sleep duration increased the risk for developing CVD.11

An analysis of over 5 million individuals found that those who slept <6 hours each night increased their risk for hypertension, coronary artery disease, and other CVDs vs. adults sleeping the recommended 7 hours or more.12

Sleep duration is not only associated with diseases of the cardiovascular system, but also with direct biological markers of CVD risk.

The amount of calcium in the blood vessels (known as arterial calcification), a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis, is higher in people with a short sleep duration.13

Coronary artery calcification (CAC) and aortic stiffness are also associated with self-reported sleep duration.14

One study of over 1,900 men found evidence that very short sleep duration predicts a higher burden of atherosclerosis in their coronary and femoral arteries.15

Sex differences

Studies that have analyzed data on males and females separately provide some interesting data suggesting that women with a short sleep duration may be at an increased risk for CVD compared to men with a short sleep duration.

Multiple studies find that the risk for high blood pressure (hypertension) is elevated in women with short sleep duration to a greater extent than it is in men.1617

In the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), sleeping less than 5 hours per night was associated with an increase in the risk for CVD in both sexes. However, when analyzing people who slept less than 6 hours per night, a greater CVD risk was only observed in women. In fact, a 60% greater risk for CVD was found in short-sleeping women, but not men.18

Women sleeping <5 hours per night had a 45% greater risk for coronary heart disease along with a 3-fold greater risk for CV events including heart attack.1920

Mortality from CVD and coronary heart disease is also increased in women with short sleep, but not men.212223

It is worth noting that the literature here is still in its infancy, as research into sex differences is currently an emerging area in physiology.

Circadian rhythms and heart health

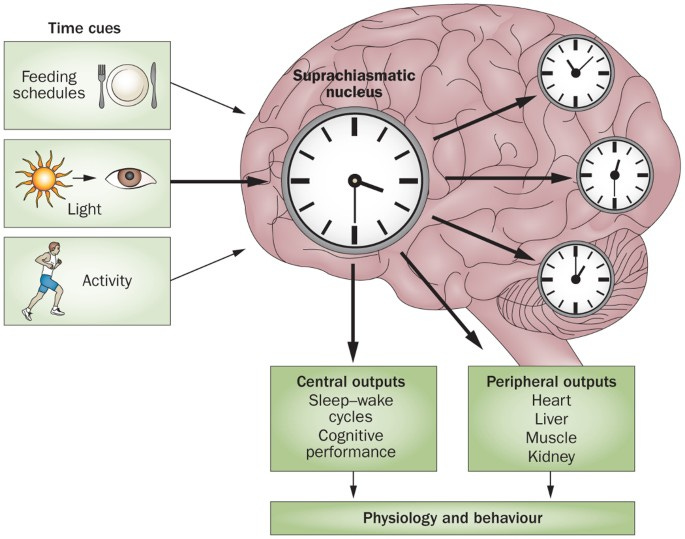

Circadian rhythms (from circa dia meaning “about one day”) are internal 24 hour clocks present in nearly all of our cells. They control processes like sleep and eating behavior, hormone release, and even some aspects of muscle performance.

An area of the brain known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is known as the “master regulator” of our body’s circadian rhythm, however, all of our organs have their own internal clock.

We have circadian rhythms in our cardiovascular system too. There is a considerable temporal variation in blood pressure, blood clotting, and endothelial function.

One well-known example of cardiovascular circadian rhythms is the fact that our blood pressure drops during the night, or so called blood pressure dipping. People who are “non-dippers” (their blood pressure fails to drop overnight) are shown to be at an increased cardiovascular disease risk compared to those whose blood pressure dips during the nighttime.

Failure to get enough sleep — or sleeping at the “wrong” time for your body (delaying bedtime or working the night shift, for instance) — can disrupt the normal daily fluctuations in vascular function, blood pressure, and other cardiovascular processes Poor sleep habits and “social jetlag” can also contribute to circadian misalignment.

Pro tip: go to bed and wake up at about the same time each day!

Irregular sleep patterns, characterized by a bedtime that varies 90 or more minutes from night to night, are associated with a greater risk for cardiovascular disease.

A single night of sleep deprivation can lead to altered gene expression for important proteins involved in circadian rhythms, the so called clock genes. In addition to affecting clock genes, sleep deprivation also induces metabolic dysfunction.4

Many environmental and lifestyle factors can throw our circadian system out of whack, which is why being prudent about sleep, diet, and exercise are crucial. Indeed, these factors are known as zeitgebers — a German word which means “time givers” — and they help to set and synchronize our circadian clocks.

Sleep and blood vessel health

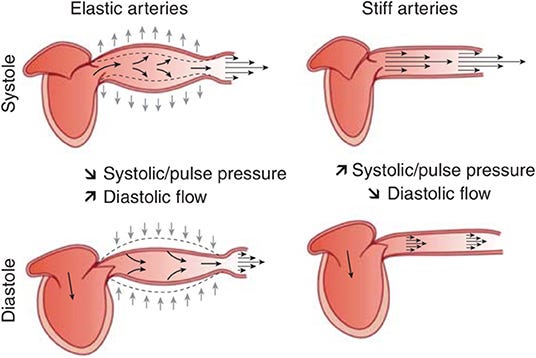

Arterial stiffness is a measure of how stiff or “inelastic” our arteries are. In general, arteries need to be elastic (think, stretchy) in order to handle the body’s large blood volume and keep blood pressure under control. Age, disease, and other conditions can increase the stiffness of our arteries, and this predisposes to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

Vascular function (also referred to as endothelial function) refers to the ability of our blood vessels to relax and contract in response to stimuli. The most common stimulus is an increase in blood flow (due to exercise), which elevates the production of nitric oxide (NO) and leads to the dilation (widening) of the artery diameter.

Some studies report that measures of arterial stiffness are associated with long sleep duration of >9 hours,1 or that people with a short sleep duration have lower (better) arterial stiffness than those with normal or long sleep duration;2 while other studies find no significant association of sleep and arterial stiffness.3

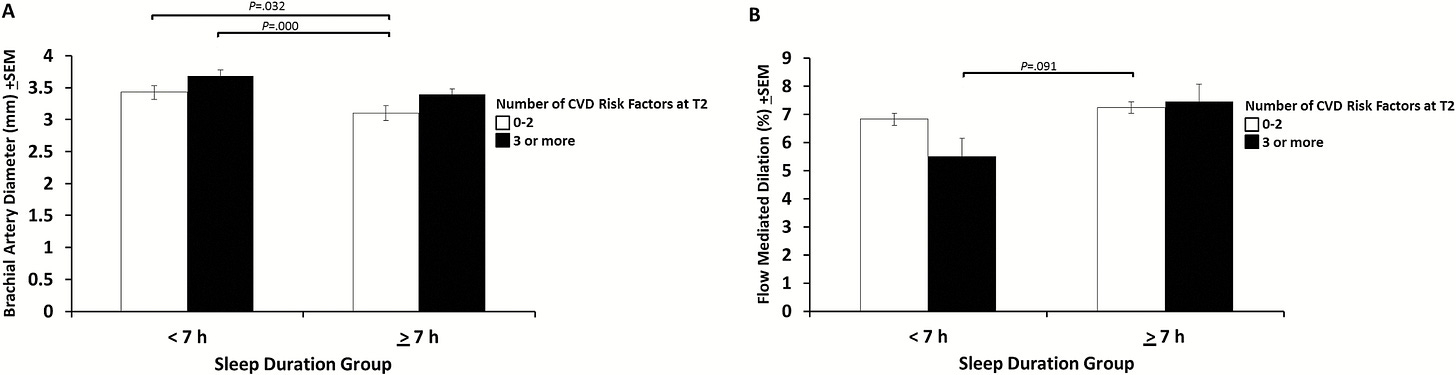

People with a short sleep duration have lower (worse) endothelial function vs. those who have normal sleep duration.56 Short sleep duration is also associated with worse measures of microvascular function, reflecting the functional ability of smaller blood vessels known as capillaries.78

Short sleep duration may also affect biomarkers related to vascular function.

Von Willebrand factor, a protein involved in blood clotting, is higher in people with a short sleep duration.9 These individuals also have higher levels of endothelin-1, which is involved in vasoconstriction and endothelial dysfunction.10

Restricting sleep for a single night increases arterial stiffness, elevates blood pressure and cardiac output,11 and reduces the elasticity of the aorta,12 even in healthy young adults.

Sleep deprivation also has consistent negative effects on vascular function.

Vascular function is reduced after extended work shifts of 24 and 30 hours.1415

A single night shift or three sequential night shifts also reduces vascular function in medical personnel.161718

Total sleep deprivation reduces microvascular function in healthy young men and rodents;1920 this has been demonstrated using sleep deprivation periods of 29 and 40 hours.2122

Similar to total sleep deprivation, sleep restriction (3—5 hours of sleep per night) for 5, 6, and 8 nights reduces arterial function, venous function, and microvascular function.2425

Sleep restriction may not have an effect on arterial stiffness, however. One study measured arterial stiffness before and after a 3-week period where sleep was restricted by 1.5 hours per night and found no change.26