Physiology Friday #215: Sitting Less Improves Blood Pressure

Don't quit your desk job. Just stand more.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

ICYMI

On Wednesday, I published The Ultimate Guide to Sleep and Cardiovascular Health.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter including Examine.com and my book “VO2 Max Essentials” can be found at the end of the post!

When you hear the word “sedentary”, you probably picture someone lying on the couch, remote control in hand, scrolling through Netflix to find the latest show to binge.

But sedentary behavior can be defined as any activity that we do when sitting or lying down (ok…almost any activity that we do lying down) that results in low energy expenditure.

We live in an activity-deficient society — sedentary behavior makes up a majority of most people’s waking hours. Even those of us who exercise for 1–2 hours per day still spend a large part of our day engaging in sedentary behavior (which, by the way, exercise doesn’t make us immune to).

Most of society probably inhabits the “physically inactive, highly sedentary” quadrant in the image below — that’s the worst place to be for health. Others are physically active for some portion of the day but highly sedentary for the rest (the upper right quadrant) — also not a good place to be from a health standpoint because one is still spending most of their time sedentary.

In the bottom left quadrant are the “physically inactive, slightly sedentary” people who may not exercise a lot, but spend most of their day walking around or engaged in activities. That’s better, but this behavioral category is missing the benefits of highly structured exercise. Finally, the bottom right quadrant represents someone who is physically active and only slightly sedentary — the epitome of health and something we should all strive for.

Society is currently facing a dual epidemic of a lack of structured exercise and too much sedentary behavior. These two phenomena may sound alike but are actually quite different. Physical activity refers to structured exercise, and someone who doesn’t meet the minimum recommendations is therefore “physically inactive” but may not necessarily be sedentary.

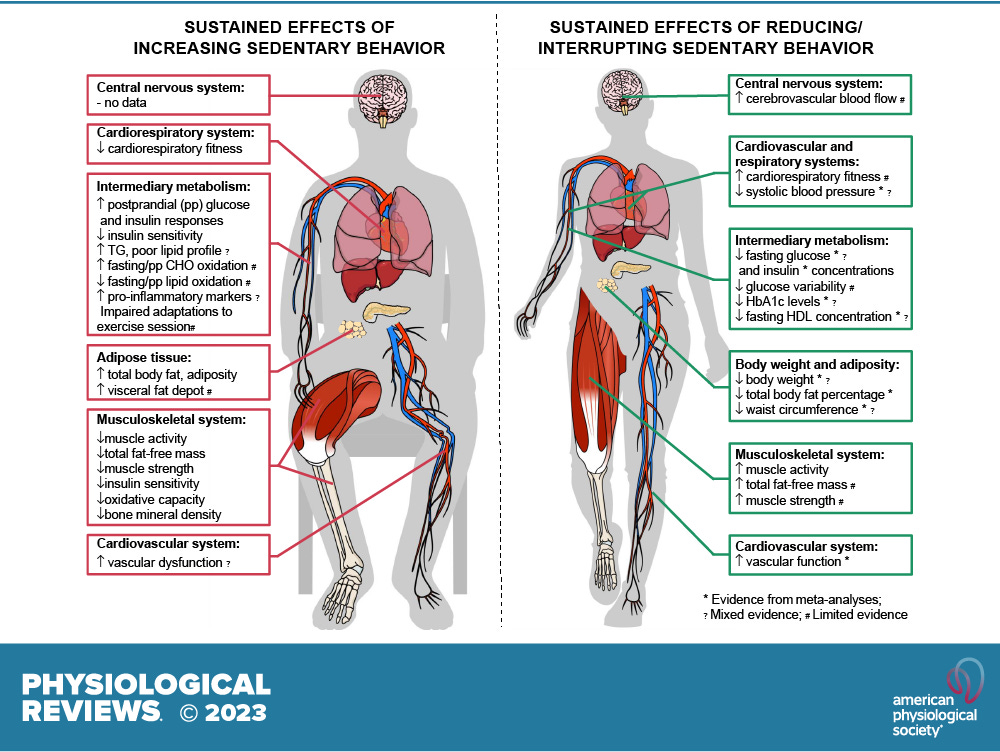

Indeed, the field of exercise physiology has been complemented in recent decades by a research field known as “inactivity physiology”, which recognizes that sedentary behavior has unique and distinct effects on our health due to its physiological characteristics.

When we are standing up or walking around (ambulating), our muscles contract to maintain posture and blood flow increases to meet the metabolic demands of the muscles. In contrast, when we’re sitting or lying down, our postural muscles don’t need to contract as much and similarly, blood flow to muscles and limbs decreases. Sedentary activity also has adverse effects on blood lipids and blood glucose. Sitting down immediately after a meal is terrible in this regard.

Prolonged sitting also leads to a bending of major arteries in our legs, leading to a blood flow pattern known as turbulent flow, blood pooling, impaired circulation, and endothelial dysfunction. Blood pressure increases during periods of uninterrupted sitting, but this can be prevented by standing up or, even more effective, performing “exercise snacks” every 30–60 minutes or so, which seem to prevent any adverse changes in endothelial function and glycemic control.

A single period of uninterrupted sitting may appear to be of little significance on any single day, but over time, the compounding effects of this behavior are alarming: body weight and waist circumference increase, fasting blood glucose and insulin sensitivity are worsened, and blood pressure rises. Being diligent about interrupting bouts of prolonged sitting is effective prevention.

All of these documented effects of sitting on health have led to a workplace “revolution” of standing desks (and for the more adventurous, treadmill desks). I’m a bit skeptical that an intervention as simple as standing up to work instead of sitting can lead to a meaningful impact on health, but that’s why it’s an interesting area of research.

A new study published in JAMA Network Open investigated the effects of swapping sitting for standing.1

For the study, a total of 283 adults with an average age of 69 (including 187 women and 96 men) were randomly assigned to one of two groups for 6 months: a standing intervention group or a control group

The standing intervention group had a goal of reducing their sitting time by 2 hours each day. This was to be accomplished through individual health coaching sessions (10 total during the study), filling out a workbook, tracking their activity using a wrist-worn device, and using a tabletop standing desk.

The rules were simple: stand more and take frequent breaks from sitting. The participants were encouraged to reduce sitting time by using inner reminders (noticing muscle stiffness during prolonged sitting), external reminders (prompts from their fitness wearable to stand up frequently), and habit reminders (advice to stand while doing common activities during the day like reading or taking a phone call).

The control group did not receive any advice or encouragement to reduce their daily sitting time. Rather, they received 10 health coaching sessions about various topics like healthy eating and sleep.

At baseline, 3 months, and 6 months, the participants physical activity was measured over a period of 7 days to calculate time spent sitting (the primary study outcome). They also had measures of body weight and circumferences and blood pressure assessed at these time points.

Results

Though they didn’t reach their sitting time reduction goal of 2 hours, the participants in the standing intervention group did sit, on average, for 32 minutes less per day compared to the control group. They also increased their time spent standing each day by 28 minutes, increased their daily step count by 160 steps, reduced the average length of their bouts of sitting by almost 2 minutes, and decreased the number of prolonged (>30 minutes) sitting bouts per day by one half of a bout per day.

Regarding blood pressure, systolic blood pressure decreased by 4 mmHg in the intervention group compared to the control group, while diastolic blood pressure didn’t change.

The intervention had no effect on body weight, body mass index, or waist circumference. Interestingly, both of the groups lost about 3.5 kilograms (7.7 lb) during the 6-month study, suggesting that the health coaching sessions may have influenced certain behaviors that promoted weight loss during the study.

Sitting for just 30 minutes a day leads to a clinically meaningful blood pressure reduction. Sounds like a fair trade to me. This blood pressure improvement is equal in magnitude to that shown for other healthy lifestyle interventions including:

Aerobic exercise training (4 mmHg reduction)

Resistance exercise training (2 mmHg reduction)

Combined aerobic + resistance training (3 mmHg)

Other types of exercise (e.g., isometric exercise; average reduction of 8 mmHg)

The dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet (3–5 mmHg reduction)

The Mediterranean diet (2 mmHg reduction)

Weight loss (4 mmHg reduction or a 1 mmHg reduction per kilogram of body weight lost)

Blood-pressure-lowering medications (5–20 mmHg reduction)

One of the main caveats about this study is that midway through, COVID-19 happened, which undoubtedly influenced the participants’ normal day-to-day activities. People became more sedentary during the pandemic (sedentary time worldwide increased by an average of 2 hours per day) because gyms closed and work-from-home became the norm. I’d say one of the main ways people accumulate non-sedentary activities is by walking to work or the grocery store — two activities that stopped during the lockdowns of 2020–2021. In other words, the behavioral strategies employed by the researchers were robust, but the environment proved to be a major barrier for the participants to reduce their sitting time.

Nevertheless, it’s promising that such a small reduction in the time you sit during the day can have a meaningful impact on cardiovascular health. Of course, I should note that the participants did have high blood pressure and an overweight/obese body mass index — these results may not be as strong for normotensive adults.

Even as someone who is incredibly physically active, I take findings like these to heart. There are plenty of times during the day when I could stand rather than sit, and I try to take advantage of each opportunity. There’s one stipulation to this: I cannot stand up while I work. I have to be comfortably seated at a table or desk on my computer. I’ve tried the standing desk thing: it’s not for me. As such, I try to stand up and walk as much as possible outside of work-related business.

Sitting is sometimes unavoidable. I don’t want to be seen as the “sitting police” and think that if you’re active and frequently taking breaks from sitting, it’s probably harmless. But we should realize that sitting isn’t benign either. Take action against inactivity and your health will flourish.

Thanks for reading. I’ll see you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

I relate to this on so many levels: "I cannot stand up while I work. I have to be comfortably seated at a table or desk on my computer. I’ve tried the standing desk thing: it’s not for me. As such, I try to stand up and walk as much as possible outside of work-related business."

I can stand up for some work but if I'm writing or doing any other work that requires deep thought, I need to be seated. Although I exercise every day and still get in my 10k steps, I spend hours sitting at my computer each day. Still trying to find more ways to add frequent walks/breaks but not always easy as a knowledge worker. I also try to floor sit at night which is good for mobility, not so sure it would impact BP any differently.

Thanks so much for writing, Brady. Love your work.