Physiology Friday #219: Could a Low-Carb Ketogenic Diet Harm Bone Health in Endurance Athletes?

Keto promises to improve your fat-burning capacity. But at what cost?

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter including Examine.com and my book “VO2 Max Essentials” can be found at the end of the post!

If there’s anyone who’s familiar with bone injuries, it’s me.

Between 2019 and 2023, I suffered one too many running-related stress fractures. This period left me searching for answers about my health, researching why my injuries kept happening, and overhauling my approach to training and nutrition (something I continue to iterate on).

Bone injuries can occur due to several factors like poor biomechanics or rapidly increasing training volume (for athletes in weight-bearing sports). But one of the biggest contributors to poor bone health in athletes is diet. Burning more calories through exercise than one consumes through their diet can lead to a relative energy deficiency which, if chronic, can have negative effects on hormones and reduce bone strength and bone mineral density (BMD), raising the risk for bone stress injuries like stress fractures.

But in addition to focusing on how much we eat to maintain bone health, what if we should also be thinking about what we are eating?

Endurance athletes commonly consume a carbohydrate-based diet, but in the recent decade, low-carbohydrate, high-fat diets or ketogenic diets have become a topic of interest. Low-carb and keto have shown promise for weight loss and cardiometabolic health, but the effects of these diets on athletic performance have been quite underwhelming, to say the least.

The one “advantage” to keto for athletes may be its effects on substrate metabolism — adhering to a low-carb diet builds the metabolic machinery that makes you a better fat burner…probably at the cost of being a worse carbohydrate burner. Indeed, this explains why short-term keto impairs high-intensity endurance exercise performance consistently.

Back to bone health. If a low-carb diet is something of interest to athletes, we’d best know about whether there could be a long-term benefit or a long-term cost to cutting carbs.

Unfortunately there’s very little known about this. Some evidence in animals and children with epilepsy adhering to ketogenic diets suggests that bone health may be impaired. But we need good data from a well-controlled study in athletes before we jump to conclusions.

That’s where today’s study comes in. Published in the journal Frontiers in Endocrinology,1 the study investigated the effects of a short-term ketogenic diet on bone health at rest and in response to exercise.

A total of 33 world-class endurance athletes (race walkers) participated in the study, including 28 men and 5 women). The research group conducting the study was led by Dr. Louise Burke, who has published several other well-known studies comparing high-carb to low-carb/ketogenic diets in elite endurance athletes. Her group is the go-to source when it comes to the performance and health effects of keto in athletes.

The participants were divided into two groups. One group consumed a high-carbohydrate diet for 3.5 weeks and the other group consumed a low-carb, high-fat ketogenic diet for the same amount of time. During the 3.5-week dietary intervention, the participants also engaged in intensive exercise training.

Importantly, both diets were isocaloric — comprising the same amount of calories and protein (2.1 grams per kilogram of bodyweight for each participant) and only differed in their carbohydrate and fat content.

Before and after the dietary intervention, the participants completed a 25 kilometer exercise test (for men) or a 19 kilometer test (for women) at 75% of their maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max). During exercise, the participants were provided with low-carb and high-carb fueling options. After exercise, they consumed a low-carb or high-carb recovery shake.

Markers of bone health and metabolism were measured before and after the intervention at several time points:

At rest in the morning following an overnight fast

2 hours after a low-carb or high-carb meal (breakfast)

Immediately after exercise

3 hours after exercise

A subset of participants in the low-carbohydrate diet group also completed one additional study visit involving acute carbohydrate restoration: outcomes were measured after a high-carbohydrate breakfast, after exercise with high-carbohydrate fueling, and 3 hours after exercise + a high-carbohydrate recovery shake.

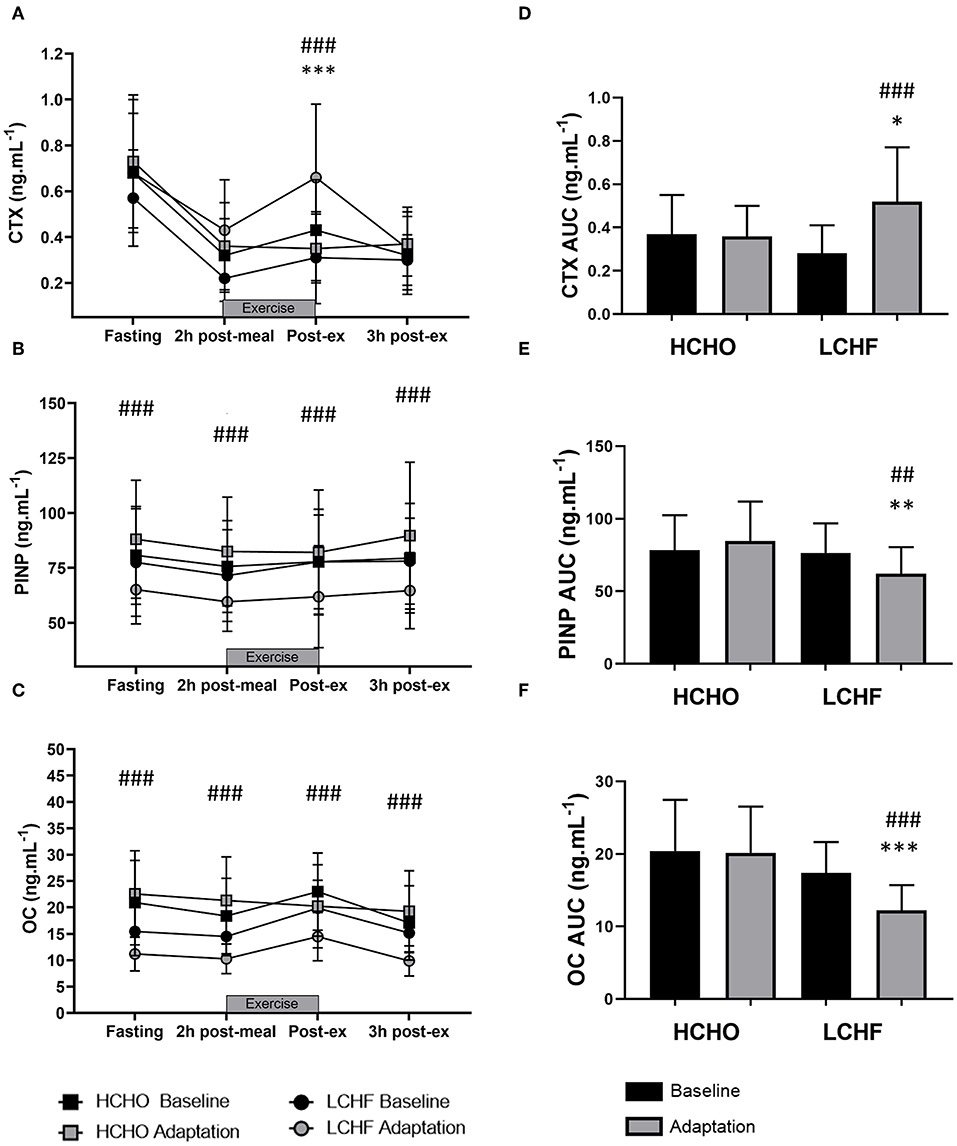

The bone health markers included

C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX): a marker of bone resorption/bone breakdown. Higher levels are bad.

Procollagen 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP): a marker of bone formation. Higher levels are good.

Osteocalcin: a marker of overall bone metabolism. Higher levels are generally seen as good.

This study design allowed several question to be answered.

First of all, it would indicate how a short-term ketogenic diet impacts bone metabolism markers at rest. Second, it would indicate how bone markers are impacted in response to exercise and meals varying in their macronutrient composition. Finally, we can learn whether introducing carbohydrates back into the diet alters markers in bone metabolism following a short-term keto diet.

Results

After the low-carb diet, fasting CTX levels increased by 22%, P1NP levels decreased by 14%, and osteocalcin levels decreased by 25% compared to baseline. P1NP and osteocalcin were also lower at rest (in the fasting state) in the low-carbohydrate group compared to the high-carbohydrate group.

These findings indicate that short-term keto negatively impacts resting levels of bone metabolism markers.

Following the exercise test, CTX levels increased in the low-carbohydrate group above baseline and when compared to the high-carbohydrate group. Levels of P1NP and osteocalcin decreased in the low-carbohydrate group compared to baseline.

The area-under-the-curve (the cumulative concentration of bone metabolism markers from immediately post exercise to 3 hours post-exercise) for CTX was 81% higher compared to baseline in the low-carbohydrate group. The area-under-the-curve for P1NP (−19%) and osteocalcin (−29%) were lower in the low-carb group compared to baseline. All of the bone metabolism markers were also different in the low-carb group compared to the high-carb group (CTX was higher and P1NP and osteocalcin were lower).

What happens when carbohydrates are restored?

In the restoration phase, CTX levels after exercise returned to baseline, however, P1NP and osteocalcin were still lower when compared to baseline levels. Similar results were observed for the area-under-the curve: CTX levels returned to baseline levels and were equal to those observed in the high-carb group, while P1NP and osteocalcin remained lower than baseline and compared to levels observed in the high-carbohydrate group.

These findings suggest that short-term keto negatively affects bone metabolism markers after exercise and that only some bone metabolism markers return to normal after acutely reintroducing carbohydrates.

One of the unanswered questions is whether the results of this study would also apply to long-term keto. Would the negative impacts on bone modeling and remodeling be sustained if one kept up the diet for 6 months, 12 months, or several years?

That’s hard to say. I think it can be argued that “keto adaptation” does take some time, although Dr. Louise Burke and colleagues argue that 3.5 weeks is sufficient time to see metabolic changes indicative of “keto adaptation.” The critics will say it takes longer. Give it a few more weeks and the markers of bone metabolism would probably return to normal.

I’m neither a critic nor a major proponent of low-carbohydrate/ketogenic diets. I think people should eat in a way that makes them feel best and have even gone “low-carb” once or twice in my life.

But these findings certainly make me weary about cutting carbohydrates as an endurance athlete concerned about optimizing my bone health. Even though we cannot conclude that these short-term changes are predictive of a greater future injury risk or negative alterations in bone mineral density, they’re enough to make me cautious.

I use findings like these to inform my own dietary strategies around training. From these data, it would seem prudent to ensure adequate carbohydrate availability before, during, and after training to promote bone health. And given most of the available data, you’ll probably experience a performance boost too.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

Hi Brady! I was explaining the study to my wife and she asked what were the carbs provided? I said it was liquid-based beverages. Is that accurate? How would you define carbs, generally? (My wife is has gradually running after injury and while she’s increasing protein intake she’s also curious about carbs.) Thanks!