Physiology Friday #228: Identifying Sleep Patterns that Influence Chronic Disease Risk

Wearable data provide a lens into how bedroom habits affect health.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

ICYMI: On Wednesday, I published my video interview with Dr. Andrew Koutnik. We talk about the ketogenic diet as a metabolic therapy for type 1 diabetes.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter including Examine.com and my book “VO2 Max Essentials” can be found at the end of the post!

“The shorter your sleep, the shorter your life.” — Dr. Matthew Walker

This statement may seem a bit hyperbolic, but it accurately summarizes most of the available research on sleep and health. Dozens if not hundreds of (albeit observational) studies have linked a short sleep duration to a number of health conditions including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. A nightly sleep duration less than 6 hours per night appears to be especially detrimental, but some studies have even shown worse health outcomes for adults sleeping 7 hours or less compared to those sleeping the recommended 7–9 hours per night.

Sleep duration has traditionally received most of the attention as a modifiable risk factor. And that’s great: it’s easy to change (just sleep longer) and straightforward to prescribe. The American Heart Association has even added sleep duration as one of its “Essential 9” healthy lifestyle factors (now to just get them to add VO2 max).

But research in the last few years has presented a strong case that other sleep metrics might be more important than sleep duration. Our patterns of sleep — not just how long we sleep — appear to strongly influence health.

One way to categorize sleep patterns is to look at something called sleep regularity. Sleep regularity refers to the consistency of one’s sleep schedule — what time they go to bed each night and wake up each morning and whether bedtimes and wake times are consistent from night to night.

An irregular sleep schedule looks something like this: Go to bed at 10 p.m. on Monday, 8:30 p.m. on Tuesday, 12:15 a.m. on Wednesday…you get the idea. You can also be an irregular sleeper with sleep duration: 8 hours Monday, 5.5 on Tuesday, and 7 on Wednesday.

This irregular sleep pattern misaligns circadian rhythms and disrupts physiology.

A regular sleep pattern, on the other hand, would mean a consistent 10 p.m. bedtime on Monday through Sunday or sleeping a consistent 7–8 hours each night. While hard to achieve, it’s optimal for circadian rhythms and health.

Sleep patterns can also be characterized by the amount of time someone spends in each of the sleep stages (N1, N2, N3, and rapid eye movement or REM sleep).

Personally, I am bullish on sleep patterns eventually usurping sleep duration as the sleep metric that we focus on. Of course sleep duration is important, but not as important (I think) as maintaining a consistent, regular sleep schedule. The impact of optimizing circadian biology on health cannot be understated.

Despite the realization that sleep patterns are likely associated with health outcomes, there’s a lack of large-scale data on this relationship, and even less data that uses objective sleep measures instead of self-reported measures.

A new study used wearable sleep data to show that several chronic diseases are associated with how we sleep.

Published in the journal Nature Medicine, the study utilized data from the All of Us Research Program — a nationwide (United States) health initiative that gathered longitudinal data on physical activity, sleep, and clinical health outcomes from over one million participants.1 Importantly, data in the All of Us program were collected from participant’s FitBit devices — providing accurate and objective measures of physical activity and sleep (some of which you probably have if you own a wearable device!)

The current analysis included 6,477 participants with an average age of 50, 71% of whom were female and 84% of whom were white. They were followed up for an average of 4.5 years.

Results

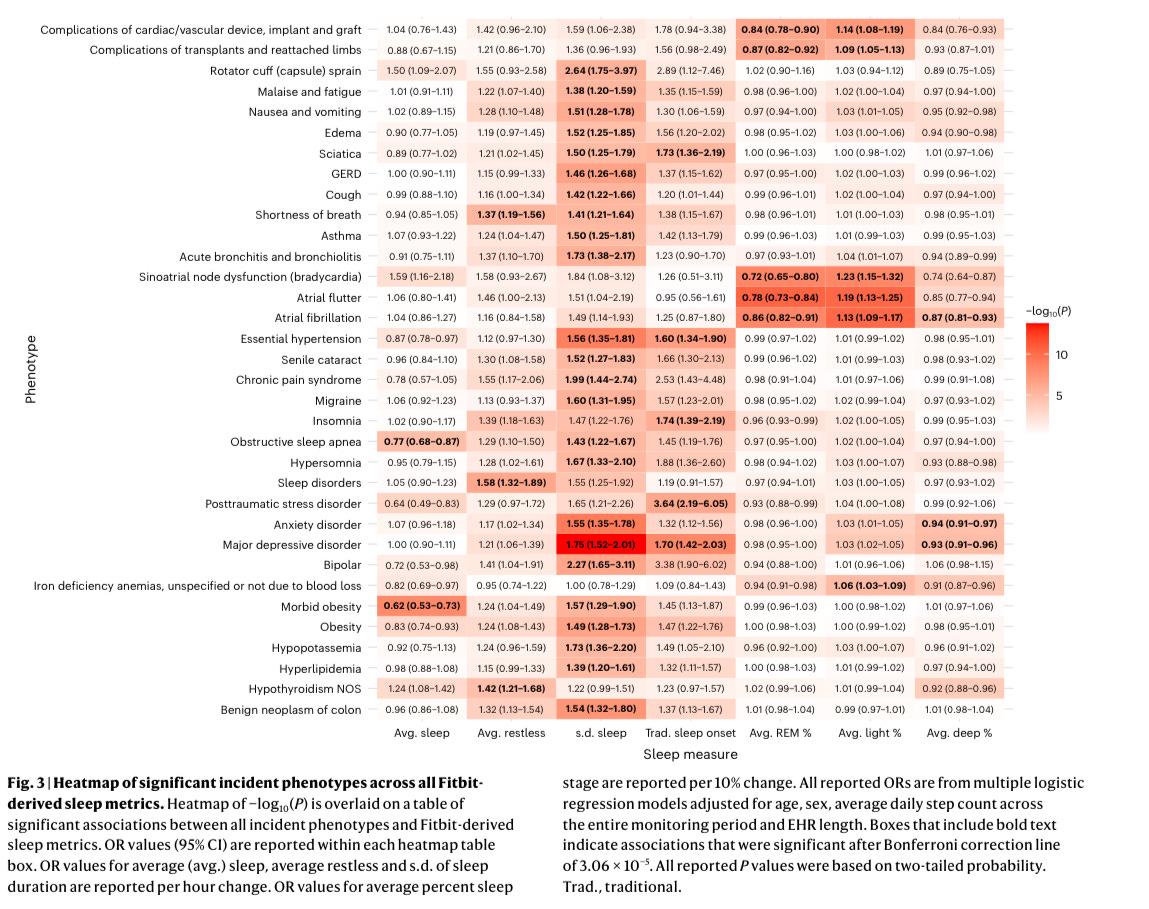

Overall, there were a total of 48 different associations of sleep patterns with chronic disease, all of which were significant even when considering the participants’ habitual physical activity levels.

For each 1-hour increase in nightly sleep duration, there was:

a 38% reduction in the risk for a new diagnosis of obesity

a 23% lower risk for a new diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea

The median sleep duration of the study cohort was 6.8 hours per night. For participants who slept just 5 hours per night, hypertension risk increased by 29%, depression risk increased by 64%, and anxiety risk increased by 46%. Sleeping longer than the median also carried a risk — a nightly sleep duration of 10 hours or more was associated with a 61%-163% increase in the risk for hypertension, depression, and anxiety!

One last important finding regarding sleep duration was the J-shaped association between nightly sleep duration and the risk of hypertension, anxiety, and depression. The lowest risk for these conditions occurred at a nightly sleep duration of around 7 hours — greater risks were observed for a sleep duration above and below 7 hours per night.

Every hour of restless sleep was associated with a greater risk of sleep disorders, hypothyroidism, and shortness of breath.

Irregular sleeping patterns were associated with a host of health conditions. Specifically, for each 1-hour increase in the variability of one’s sleep duration (referred to as the standard deviation of sleep duration), there was a 56% greater risk for hypertension, a 39% greater risk for high cholesterol, and a 49% greater risk for obesity.

Furthermore, irregular sleep was linked to the risk for psychiatric disorders including depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder, as well as conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux, sleep apnea, asthma, and migraine.

Importantly, most of the associations between sleep irregularity and health conditions remained significant even after adjusting for nightly sleep duration.

Now let’s talk about sleep stages.

REM Sleep: Each percent increase in nightly REM sleep duration was associated with a lower risk of atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and bradycardia (an abnormally slow heart rhythm).

Light sleep: Each percent increase in light sleep was associated with a greater risk of atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, bradycardia, and iron deficiency anemia.

Deep sleep: Each percent increase in deep sleep was associated with a lower risk of atrial fibrillation, depression, and anxiety.

Going to bed at a “normal” time of day also appeared to be highly impactful to health.

Adults who had fewer nights where they went to bed in the “normal” sleep window of 8 p.m. and 2 a.m. (the median sleep onset was 11:10 p.m.) were at a greater risk for depression, PTSD, insomnia, hypertension, and sciatica. Each 10% decrease in the number of nights with a bedtime within “normal” hours was associated with a 19% increase in hypersomnia (daytime sleepiness) and a 37% increase in circadian rhythm sleep disorders.

That was quite a lengthy but informative results section. Here are a few of my main takeaways.

Targeting a sleep duration of 7 hours each night is likely to reduce the risk of several chronic cardiometabolic diseases along with anxiety and depression: more sleep may not be optimal.

Your nightly sleep duration shouldn’t vary by more than 1 hour from night to night: this increases the risk for cardiometabolic and psychiatric conditions.

Sleep quality matters: spending more time in REM and deep sleep lowers the risk for chronic diseases, while restless and light sleep increase the risk. The cardiovascular system appears to be primarily affected here.

Keep a regular bedtime: too early or too late negatively impacts health, while a “Goldilocks zone” between 8 p.m. and 2 a.m. seems to be associated with the lowest health risks (though I’d argue 2 a.m. is a bit too late for most.)

Even though this study found that sleep duration is still important for health, I think that its findings underscore how vital a consistent, regular sleep pattern is if you want to stay well. This is a practical and reassuring finding because it means even if you don’t get enough sleep, having a regular sleep schedule can protect you from developing a cardiovascular, metabolic, or psychiatric condition.

Of course, we can’t rule out reverse causation for many of these associations — sleep apnea, insomnia, anxiety, depression, migraine, and “heartburn” may all very well be causing poor sleep and not the other way around.

In reality, it’s likely a vicious cycle whereby these conditions predispose to poor sleep, poor sleep exacerbates these conditions, and so on. One downward spiral into poor health.

And that’s why those of us who don’t already have a chronic disease should be especially prudent about our sleep hygiene. Bad sleep habits can be hard to break out of, but good ones can be easy to maintain.

Regular sleep habits will not only keep us in good health, but also keep our body’s circadian rhythms in check, allowing us to maintain healthy exercise habits, be productive in our jobs, and show up for our family and friends.

The coolest part about these results? All of us who own a wearable sleep tracker can analyze our data, identify areas where we are lacking, and take action. We have access to how long we sleep, how much time we spend in the sleep stages, and other important metrics literally at our fingertips (or wrist). This could be life-saving or life-enhancing information when used correctly!

Sleep well (and regular).

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.

"even if you don’t get enough sleep, having a regular sleep schedule can protect you from developing a cardiovascular, metabolic, or psychiatric condition" This is reasuring when there is a time having enough sleep just isn't possible. Very good to know. Thank you.