Physiology Friday December in Review

A wrap-up of research studies I covered this month + some practical takeaways.

Greetings!

In case you missed it, here’s a quick summary of all of the research I covered this month in the Physiology Friday newsletter. Each is summarized in a few paragraphs with a few of my key takeaways. I’ve also included links to each post if you want to read the whole thing (again… or for the first time).

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter and deals on products, including Ketone-IQ, Create creatine, Equip Foods, and ProBio Nutrition can be found at the end of the post.

Physiology Friday #296: Can Excessive Exercise Cause Cognitive Decline? (Dec 5, 2025)

This study tackled an uncomfortable (but important) question: Is there a point where more vigorous exercise stops being brain-protective and starts becoming a liability?

At the population level, UK Biobank data (316,678 people) showed a classic J-shaped curve: cognitive-impairment risk dropped as activity increased, bottomed out around 3,972 MET-min/week (≈ 27% lower risk), then rose again at the extreme high end. When zooming in on vigorous activity, the “sweet spot” was about 1,216 MET-min/week (again ~27% lower risk), with the curve bending upward beyond that. The mechanistic work is the real novelty of this study: in overtrained mice, excessive vigorous exercise impaired memory and damaged hippocampal synaptic structures, and the culprit appears to be muscle-derived mitochondria-related vesicles (“mitochondrial pretenders”) that cross into the brain and disrupt synaptic energy production.

In humans, plasma lactate correlated with circulating mitochondrial-derived vesicles after exercise, and in a 6-week training study, an “excessive” vigorous group ramping up to 450 min/week showed higher levels of these vesicles, worse hippocampal energy ratios, and declines in fluid intelligence and numeric memory.

My key takeaways

The signal isn’t “exercise harms the brain,” it’s that there may be a ceiling for productive high-intensity volume, especially when lactate accumulation is repeatedly pushed past a threshold. The danger zone is chronic, high-volume, near-maximal work.

The “mitochondrial pretender” mechanism is fascinating because it’s not just correlational! Overtrained mitochondria-derived vesicles were causally harmful in mice, and blocking their secretion protected against decline.

If this line of work holds up, mitochondria-derived vesicles could become a practical biomarker to detect “overtraining.”

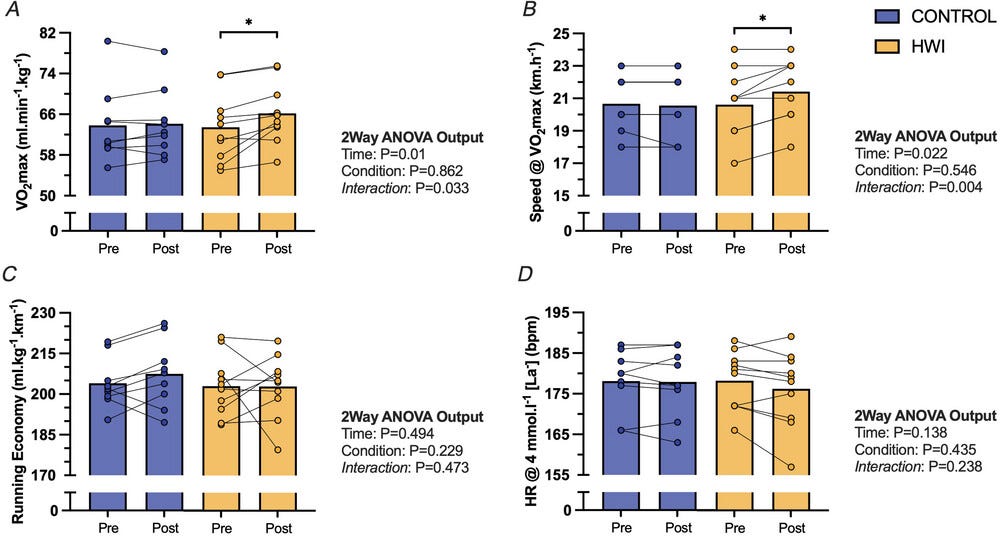

Physiology Friday #297: Post-Workout Hot Baths Provide a VO₂max Boost (Dec 12, 2025)

What if you could get a meaningful VO₂max bump without changing your training by stacking passive heat exposure after workouts? Heat training may be a form of “altitude in disguise.” In a 10-person crossover intervention in well-trained runners using hot-water immersion at 40–42°C/104–107°F, over 5 weeks, VO₂max increased by ~2.7 mL/kg/min (about 4.4%) and speed at VO₂max improved by ~0.8 km/h (0.5 mph)—essentially raising the runners’ ceiling while running economy and lactate threshold (submaximal performance) didn’t move.

Mechanistically, the gains looked like classic endurance adaptations—hemoglobin mass rose (~4%) with increases in blood/plasma/red cell volume, alongside cardiac remodeling in the direction you’d want for endurance (higher left ventricular volume and stroke volume, plus higher resting cardiac output).

The study was small and short, but the effect size is meaningful partly because VO₂max is so predictive—meta-analyses suggest each 3.5 mL/kg/min higher VO₂max links to ~13% lower all-cause mortality and ~15% lower CVD events.

My key takeaways

Hot baths aren’t a replacement for training, but they are a multiplier when you can tolerate the added stress.

If you try it, your protocol should be: 4–5 sessions/week, 30–45 minutes at 104–107°F, scaling up from ~15 minutes as you adapt (45 minutes is a LONG time).

The most believable mechanism is more oxygen delivery + a bigger pump from higher hemoglobin mass/blood volume and higher left ventricular volume/stroke volume.

I don’t want to oversell a single 10-person, 5-week study—but the physiology is coherent, and the magnitude (+2.7 mL/kg/min) is big enough to care about if replicated.

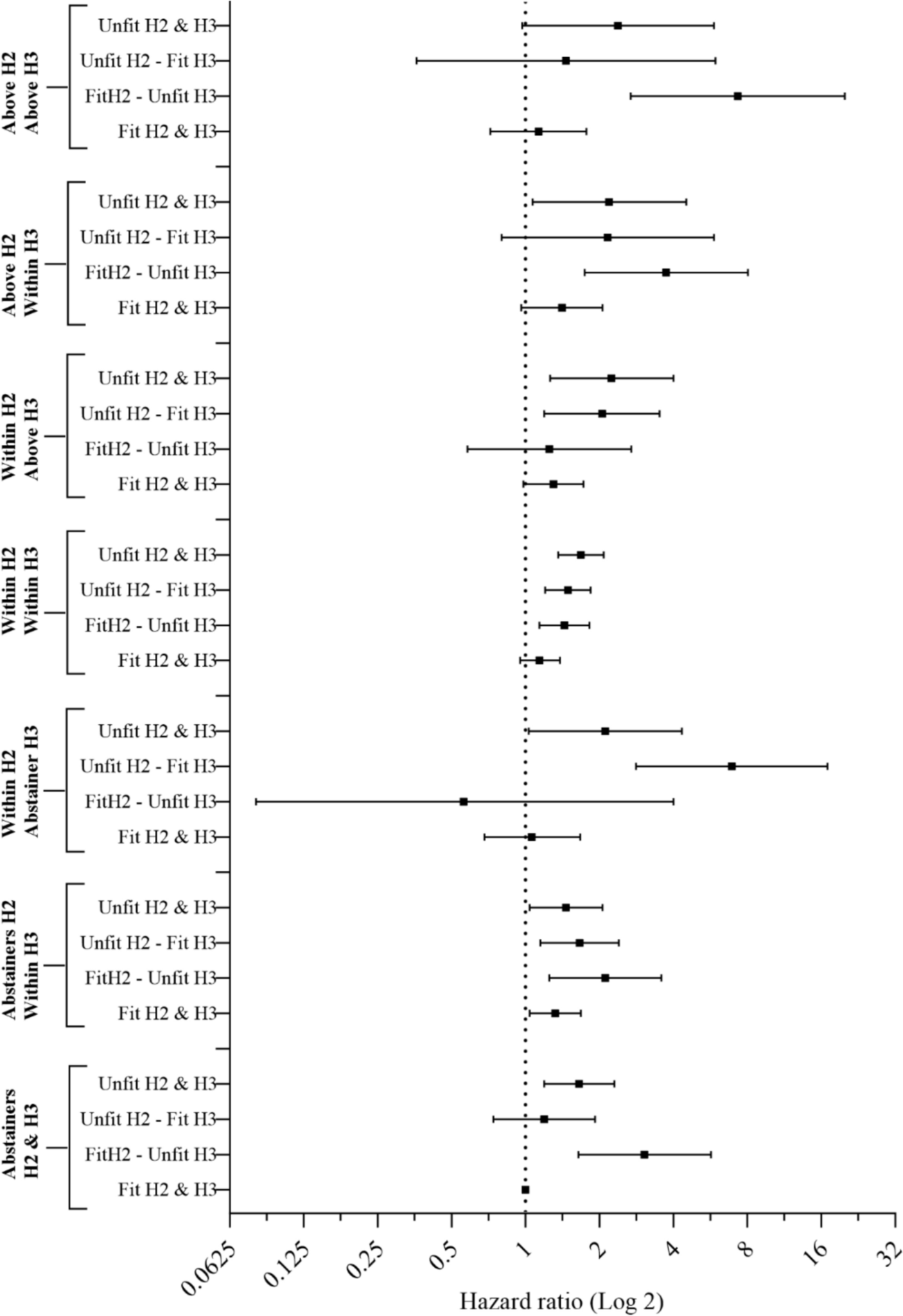

Physiology Friday #298: Does Being Fit Make Alcohol Harmless? (Dec 19, 2025)

This study asked a question that some people want an answer to: Can high fitness “cancel out” alcohol risk? The data come from a large Norwegian cohort design (HUNT2 → HUNT3) of 24,853 initially healthy adults, looking at changes in alcohol intake (abstainer/light/moderate/heavy) and changes in estimated VO₂max/fitness (fit vs unfit) over ~10 years of follow-up. The headline is nuanced. Drinkers often looked worse than persistent abstainers—but the interpretation gets messier when people change their behavior, illustrated by the counterintuitive finding that reducing alcohol intake was linked to 16–42% higher risk (possibly due to a classic case of the “sick quitter” effect).

The more interesting result is the interaction. Fitness status and (especially) fitness decline seemed to dominate the risk picture. Those who stayed at the bottom fitness bracket had a worse mortality profile across drinking patterns, and the fit → unfit transition was notable—among abstainers, dropping from fit to unfit was associated with a 205% higher risk compared to staying fit, and among drinkers it was 48% higher. Even persistent abstainers who remained unfit had a 65% higher risk relative to fit abstainers. Meanwhile, moving from unfit to fit looked protective (~18% lower risk). Meanwhile, those who stayed fit but consumed alcohol didn’t have a meaningfully higher all-cause mortality risk than fit people who abstained from alcohol or consumed less.

My key takeaways

Fitness isn’t a “license to drink,” but the data here suggest that protecting (or building) fitness may be a bigger lever than people want to admit. In fact, protecting and building fitness appears more powerful (from a mortality perspective) than obsessing over drinking habits.

The scariest pattern wasn’t “moderate drinking while fit”—it was losing fitness, especially from a high baseline (fit → unfit), regardless of changes in drinking patterns.

If you take one practical message: keep a fitness floor year-round—because once you fall out of it, the risk picture can change fast.

Ketone-IQ is high-performance energy in a bottle. I use it for post-exercise recovery along with enhancing focus, mood, and cognition. Take 30% off your order.

Create is the first “modern creatine” brand. They sell a wide range of creatine monohydrate gummies—and yeah, their gummies actually contain creatine, unlike some other brands. They’re giving my audience 30% off their order this week. So stock up!

ProBio Nutrition—the all-in-one supplement that I use every single day—is offering 20% off. My preference is the tangy orange flavor, but they also sell an unflavored “smoothie booster” that’s great in a shake, smoothie, or juice.

Equip Foods makes some of the cleanest, best-tasting protein products around. I am absolutely obsessed with their Prime grass-fed protein bars (the peanut butter ones are to die for). Take up to 10% off site-wide!