Physiology Friday #221: The Optimal Balance of Sleep, Sitting, and Exercise for Metabolic Health

Spend your time wisely.

Greetings!

Welcome to the Physiology Friday newsletter.

Details about the sponsors of this newsletter including Examine.com and my book “VO2 Max Essentials” can be found at the end of the post!

There are only so many hours in a day.

24 to be exact. And each of us must decide how to use them.

Most of us have jobs to work and families to care for, but that’s not what we’re referring to here.

Rather, every day provides an opportunity to allocate time to activities that can promote or detract from our health: how much we sleep, how much time we engage in exercise, and how much time we spend in sedentary activities like sitting.

Think about each day like a clock that’s divided into small little slices — a pie chart. Occupying each of those slices is one of the three activity buckets mentioned above.

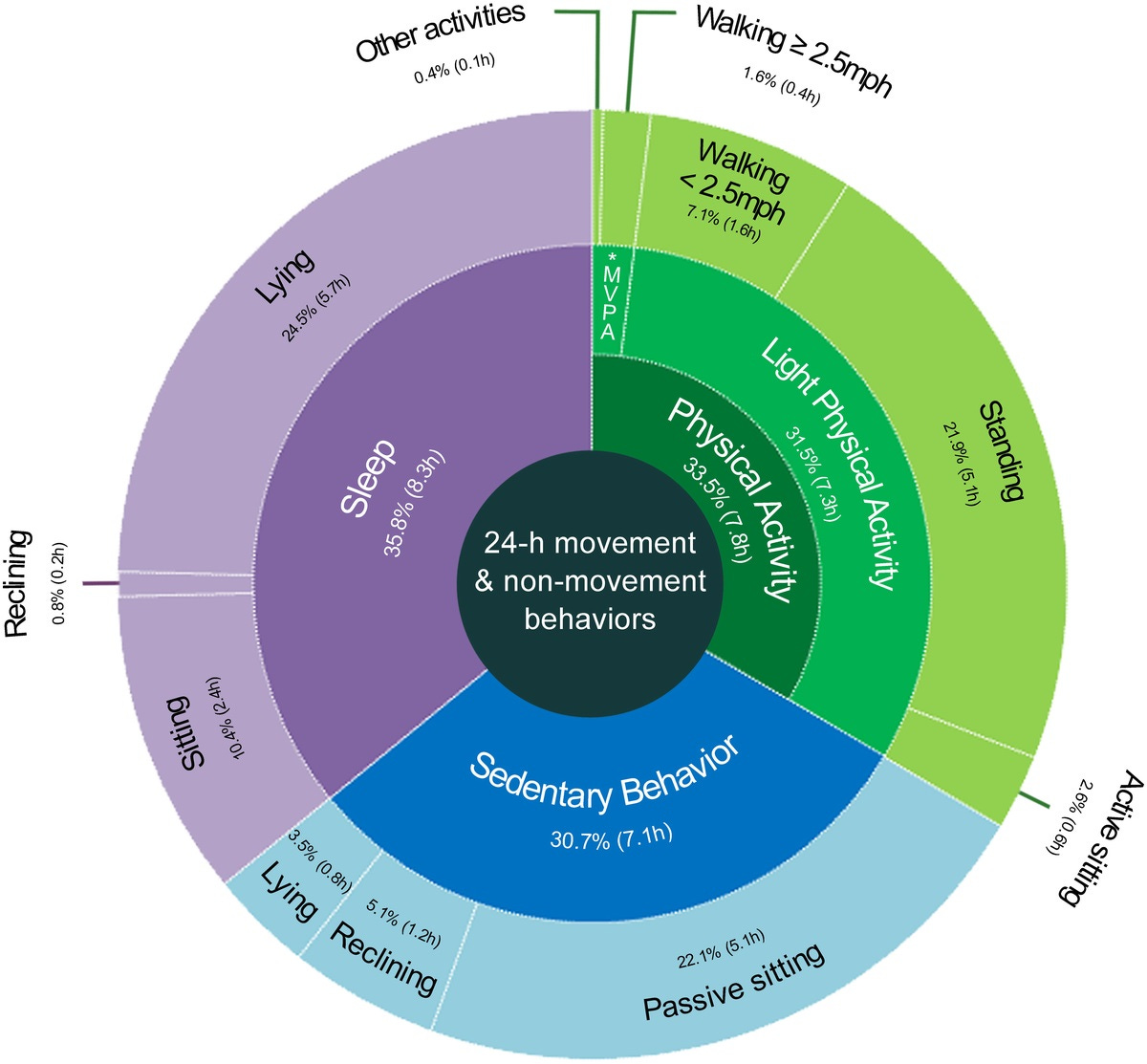

How we spend our time in these activities is referred to as the 24-hour movement spectrum.

The 24-hour movement spectrum has a significant impact on our health. Prolonged bouts of sitting negatively contribute to health by causing endothelial dysfunction, blood pressure elevations, and glucose dysregulation.

Failing to engage in enough physical activity each day is one of the largest contributors to poor cardiovascular and metabolic health around the world. Barely 25% of adults meet the minimum 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity each week. We’re living through an epidemic of inactivity.

Lastly, insufficient sleep is also a massive health liability, leading to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cognitive decline.

All of us are seeking to find the perfect recipe of sleep and physical activity that leads to optimal health. It’s a journey that takes experimentation and refinement. That’s because doing more of one thing means we have to do less of another. Our time isn’t unlimited. If you choose to sleep an extra hour each night, that might come at the expense of another hour of physical activity.

The question then becomes if this was a worthwhile substitution. I’ve asked myself this question several times in the middle of an early morning workout that I sacrificed a few hours of sleep for. Is this helping or hurting my health?

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could glean some advice from science? What’s the best way to spend our time when health is the outcome of interest?

A new study in the journal Diabetologia tries to provide some insight.1

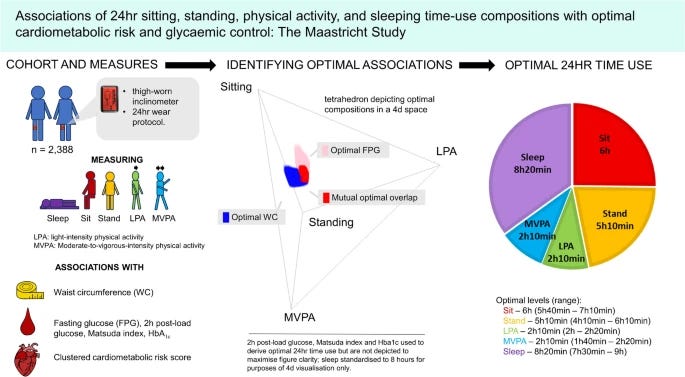

This observational study included a total of 2,388 participants from Denmark with an average age of 60 — about half of whom were male and half of whom were female.

The participants wore an activity-tracking device on their thigh for a total of 8 days. This activity monitor constantly measured the participants’ step counts and activity, which were used to calculate outcomes related to their daily activity types, including:

Sitting time

Standing time

Low-intensity physical activity

Moderate to vigorous physical activity

Sleep

The researchers were interested in a few main questions.

For one, they investigated how different compositions of activity — for example, a composition with greater sitting time, more sleep time, or less low-intensity exercise — influenced metabolic health outcomes.

They also investigated how replacing 30 minutes of sitting time with 30 minutes of sleep or physical activity would influence each health outcome. A simple substitution analysis.

Finally, they sought to calculate the optimal composition of daily activity. Which combination of sleep, sitting, and physical activity is associated with the best metabolic health?

Speaking of metabolic health, here were the outcomes that were assessed:

Fasting blood glucose

Waist circumference

2 hour postprandial glucose

HbA1c

Insulin sensitivity

Cardiometabolic risk score (a composite of waist circumference, glucose, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, and blood pressure)

Results

Unsurprisingly, spending more time engaging in low-intensity or moderate to vigorous physical activity in combination with less sitting was associated with more favorable metabolic health markers. Engaging in more moderate to vigorous activity yielded greater benefits for waist circumference, while low-intensity activity yielded more favorable fasting glucose levels, better 2-hour postprandial glucose, and a lower HbA1c.

Spending more time standing (and less time sitting) was also associated with a lower waist circumference and a better cardiometabolic risk score. Spending more time sleeping at the expense of standing had benefits for HbA1c.

Here’s a finding I found powerful: spending more time sleeping at the expense of low-intensity activity or moderate to vigorous intensity activity was adversely associated with metabolic health markers. Maybe I’m not so misguided when I cut sleep short for a workout.

Overall, the benefits associated with replacing sitting with physical activity were stronger in people with impaired fasting glucose or type 2 diabetes, in particular HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose.

The optimal amount of time for each designated activity differed depending on the cardiometabolic risk factor being considered. To use just a few examples:

Spending about 7.5 hours asleep was associated with the most favorable waist circumference, fasting plasma glucose, and cardiometabolic risk score, while 9.5 hours of sleep tended to favor a better 2-hour postprandial glucose and HbA1c.

The best outcomes for waist circumference, insulin sensitivity, and cardiometabolic risk score occurred at around 2 hours of moderate to vigorous physical activity each week, while fasting blood glucose and 2-hour postprandial glucose benefitted from less — about 50–120 minutes per day.

Regarding sitting time, less than 7 hours per day benefitted fasting glucose, waist circumference, and cardiometabolic risk, while more than 7 hours of sitting led to better 2-hour postprandial glucose, HbA1c, and insulin sensitivity.

What was the optimal daily activity composition?

6 hours of sitting time per day

5 hours 10 minutes of standing time per day

2 hours 10 minutes of low-intensity physical activity per day

2 hours 10 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per day

8 hours and 10 minutes of sleep per day

I despise the word “optimal” despite it being a considerable part of my lexicon.

What does “optimal” even mean? What does “optimization” look like?

Regardless of what science tells us, “optimal” is always going to be individual. I think one is optimized if they’re meeting their health and performance goals within the context of everything else going on in life.

Will your daily schedule look like the “optimal” one proposed above? Maybe not. But I certainly think that we can look at the breakdown of activities and formulate a good plan of action to promote cardiometabolic health, especially if any of these numbers falls above or below the amount of time you’re currently spending in each activity.

An important note from this study is that none of the sample averages from the cohort matched the optimal duration for any of the activities. In other words, they were falling short of healthy daily activity patterns.

To see that 8 hours of sleep is optimal is not a surprise — it’s recommended that adults get between 7–9 hours of sleep each night. In this study, the participants got 8 hours and 10 minutes of sleep on average (falling just 10 minutes short of the optimal sleep duration).

Sitting for just 6 hours per day (the optimal amount) also seems like a reasonable ask, but most of us probably sit a lot more. The participants in this study sat for an average of 9 hours 20 minutes each day — more than 3 hours than they should be. They also spent less time standing (4 hours and 10 minutes) than the optimal 5 hours 10 minutes.

As for physical activity, this is an area where most people would like to improve. The participants in this study average just 1 hour of low-intensity and 50 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity each day — less than half of what is recommended based on the optimal amount.

I will note that, rather than using self-reported physical activity/exercise habits, this study simply used step frequency to calculate exercise intensity, which is hardly the most robust measure.

Nevertheless, it seems as if optimal cardiometabolic health is achieved at a level of physical activity that far exceeds the minimum recommendations (in the United States at least). In fact, the optimal daily physical activity is right around the recommended weekly duration of physical activity. Maybe we need higher standards.

If there’s one thing to learn from this study, it’s that we should try to be a bit more calculated (literally, perhaps) about how we structure our 24-hour movement patterns. While you don’t have to run a cost-benefit analysis (though you could) on your health habits, all of us should at least tinker around with investing our time in different buckets and seeing how our health responds.

Replacing 30 minutes of sitting tomorrow with standing or some low-intensity activity is a cost-free experiment that will probably have health benefits. And it could become a regular part of your health routine.

Thanks for reading. See you next Friday.

~Brady~

The VO2 Max Essentials eBook is your comprehensive guide to aerobic fitness, how to improve it, and its importance for health, performance, and longevity. Get your copy today and use code SUBSTACK20 at checkout for a 20% discount. You can also grab the Kindle eBook, paperback, or hardcover version on Amazon.

Examine.com: Examine is the largest database of nutrition and supplement information on the internet.